The Vets v. Veterans Affairs

Powers v. McDonough is a class action lawsuit brought against the federal government by disabled veterans in Los Angeles County seeking permanent housing on the West Los Angeles VA campus. Stay current on the case through daily court briefings. The updates are available via an email newsletter, and will be reproduced in their entirety here.

GET UPDATES FROM THE FRONT

Follow the veterans’ fight for housing at the West LA VA and receive daily court briefings from the trial.

Tuesday, June 11, 2024

For roughly two weeks beginning August 6, 14 unhoused U.S. military veterans will challenge the federal government for access to housing on the West Los Angeles Veterans Affairs campus. Their lawsuit alleges that “despite a lawsuit, two Acts of Congress, and two reports of the Office of Inspector General detailing the VA’s failings, the West Los Angeles VA’s Master Plan 2022 will leave thousands of veterans to live and die on the streets of Los Angeles for many years to come.” The government’s response to the suit argues the court lacked jurisdiction to rule on the matter and that it doesn’t owe a fiduciary duty to the veterans. Nevertheless, the trial is scheduled to commence this summer.

The issue at stake isn’t just the fate of these service members — or even the wider class of unhoused veterans who have become a party to the case — but perhaps an entirely new way of approaching veteran care. If VA’s mission is to care for those ‘who shall have borne the battle,’ where does that care begin and end? This case may ultimately extend the VA’s purview beyond its hospital walls and into the realm of housing, as it originally was on the property in question.

The West LA VA is a 388-acre campus originally donated to the federal government in 1888, following a law signed by Abraham Lincoln establishing the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers — a predecessor to the VA we know today. The land’s deed stipulated that the plot be used to “permanently maintain” housing for disabled volunteer soldiers, which it did until the early 1970s. At its peak in the late 1950s, 5,000 veterans made their homes on the property. Fifteen years later, all the vets were evicted from the land, and have been fighting for housing on the campus ever since. More than 3,800 unhoused service members live on the streets of LA County today.

This space will be updated with breaking developments in the Powers v. McDonough litigation, from pretrial procedures through the lawsuit’s conclusion. Bookmark this page to follow along, or subscribe above to receive updates as a daily email newsletter, once the trial begins.

Monday, July 15, 2024

In a surprise ruling filed July 14, U.S. District Judge David O. Carter found in favor of a class action of Los Angeles County disabled veterans, saying the Department of Veterans Affairs had entered into a charitable trust when it accepted a gift of hundreds of acres donated in 1888 for the specific purpose of building veterans housing.

The land is currently the site of the West LA VA, which for decades has been a flashpoint in a housing crisis disproportionally affecting military veterans. “Los Angeles is the homeless veterans’ capital of the United States,” Carter writes in his ruling. The line echoes the opening of Long Lead’s Home of the Brave feature, published last month.

In the summary judgement filed Sunday, Carter also ruled that the VA has discriminated against veterans through its practice of leasing areas of the West LA VA campus to third-party developers who finance project-based housing developments through funding sources that require income restrictions for their residents. As a result, veterans who are more severely disabled (and therefore receive higher disability payments) are not allowed to live in on-campus housing closest to the medical facilities where they receive care.

“That third-party developers, not the VA, are the ones directly imposing the discriminatory conditions is of no consequence,” Carter writes in the ruling. “Defendants cannot outsource discrimination.” This discriminatory practice is outlined in “Carving up the Map,” Part 4 of Home of the Brave.

Carter’s summary judgement comes weeks ahead of the August 6 trial start date for Powers v. McDonough, in which the class alleges “despite a lawsuit, two Acts of Congress, and two reports of the Office of Inspector General detailing the VA’s failings, the West Los Angeles VA’s Master Plan 2022 will leave thousands of veterans to live and die on the streets of Los Angeles for many years to come.”

Summary judgements can be issued when a party argues that the material facts of a case are not in dispute. In this case, both the veterans and the VA moved for the ruling, and while Carter did find for the plaintiffs in both these instances, he notes that other issues in the case are yet to be decided.

Among the claims to be sorted through — now that Carter has determined that the VA has a fiduciary duty to veterans under the charitable trust it entered into by accepting the land — is whether the VA breached its trust by leasing out the property to outside interests. This is an argument veterans have made going back to the Vietnam war, as well as in their current case which was filed in November 2023.

The overarching issue yet to be decided at trial is whether permanent supportive housing is “necessary to ensure that Plaintiffs have ‘full and equal enjoyment’ of their healthcare benefits,” Carter writes.

Tuesday, August 6, 2024

Powers v. McDonough began Tuesday, a historic lawsuit over discrimination claims brought by a class of military veterans against the Department of Veterans Affairs over housing at the West Los Angeles VA campus, a 388-acre property donated to the federal government in 1888 specifically to house disabled veterans.

“We talk a lot about the problems. There are solutions, and the solutions to veteran homelessness are multifaceted, but each and every one of these, your honor, is achievable,” plaintiff’s lawyer Roman Silberfeld, a partner at Robins Kaplan LLP, told U.S. District Judge David O. Carter in his opening statement.

“People may disagree about financing and construction methods,” said Silberfeld, “but I don’t think there’s disagreement that housing on campus is a necessity.”

Carter ruled in July that the VA, which is contracting with third-party developers to build HUD-backed housing that comes with income limits on the West LA VA campus, is discriminating against unhoused veterans who are deemed ineligible for the housing because their disability payments put them over HUD’s threshold. The judge said the VA has a fiduciary duty to use its 388-acre campus for housing and health care. Right now, the VA leases parts of the West LA property to outside groups for athletic facilities, oil-drilling, and public parking.

The judge’s recent orders don’t say how exactly the VA should change its services and approach to land use, and attorneys on both sides offered different ideas on Tuesday about what to do.

Silberfield detailed the history of the VA campus and explained how its property has been used for sports fields for UCLA, the Brentwood School. He said one acre of land “will support about 40 or 50 temporary support housing units.”

“So the objective is to place 1,000 temporary supportive housing units scattered around the property,” Silberfield said. “And that would require about 25 acres.”

Silberfield also told Carter he’ll hear testimony from Steve Soboroff, a Los Angeles developer who will testify about an “urgent need to place approximately 1,000 temporary housing units on the campus.” Another 2,800 additional permanent units would replace the 1,000.

“He knows what to do,” Silberfield told Carter. “He’s identified the six priority sites and the three potential sites.… He can provide an overview of planning and execution on the project.”

Soboroff believes “a new leadership leadership structure is needed.”

Soboroff’s testimony will be complemented by testimony from developer Randy Johnson, who “also is of the view that 1,000 temporary housing units can be built on the property in 12 to 18 months to make a robust impact on homelessness in the veteran population.”

Johnson’s broader plans have a billion dollar price tag, but “that figure has a cushion in it because more information is needed in order to refine that estimate.”

Silberfield ended his opening by telling Carter he suspects VA attorneys “will get up here and say these things are impossible.”

But, “the VA has had a decade and a half to solve this problem. There are grievances about the use of this property that go back 50 years.”

“The time is up, your honor. It’s time to actually do something,” Silberfield said.

Brad Rosenberg, a special counsel at the Department of Justice, began his opening for the government by telling Carter the lawsuit “is a curious case.”

“Everyone in this courtroom has the same goal in mind — everyone wants to end veteran homelessness,” Rosenberg said.

However, “the parties have vastly different views as to how to achieve that goal.”

“Planners have focused on the campus, and to be sure, the campus is an important part of the puzzle of ‘how do you solve veteran homelessness in Los Angeles,’ but it’s only one part of that puzzle,” Rosenberg said.

Currently, “over 5,300 formerly homeless veterans” are housed in the “broader” Los Angeles community with the assistance of vouchers, Rosenberg said. The most recent count of homeless veterans “showed a 32 percent decrease” in Los Angeles and a 23 percent decrease “in the Los Angeles continuum of care,” which includes most of Los Angeles County.

“To be sure, there is still work to be done, but those are significant numbers and significant achievements,” he added.

Rosenberg said the plaintiff’s proposal for the VA campus seeks to have Carter “throw out… VA’s plans that were developed after multiple rounds of public input.”

“Simply put, and as we will show through evidence in this case, plaintiff’s billion dollar idea for the development of the West LA campus is unmoored from reality,” Rosenberg said.

He said the lawsuit is “not just about housing or housing homeless veterans in the abstract.”

“It’s about services that the agency provides and the medical needs of many in the veteran community,” he said. “It’s not about housing veterans generally. To be sure, that’s part of VA’s mission, and VA is working very hard on achieving that goal.”

But, he said, “plaintiffs are going to have to tie it to medical benefits and the services the VA provides.”

Rosenberg said delays in housing construction are partly the VA’s fault, “but there’ll be testimony about how many of these delays were outside of VA’s control.”

“Remember, this is a campus with infrastructure that, in some cases, is well more than 100 years old,” Rosenberg said. “You’ve got to get your arms around that before you can figure out what the development’s going to look like.”

Rosenberg also invited the judge to tour the campus himself as part of the trial. “I’m sure there’s a way that we can get that on the record and the court would have the opportunity to see VAs efforts at developing the campus in real time,” Rosenberg said. “We have nothing to hide.”

Carter has not yet said if he’ll accept the invitation.

Witnesses on Tuesday included Robert Reynolds, a veterans advocate, Iraq war veteran and former U.S. Army specialist and infantryman. He testified about the horrors he experienced in war and the lack of support he had from the VA after returning home.

“Did anyone from the VA reach out to you and talk to you about obtaining benefits?” asked plaintiff’s lawyer Mark Rosenbaum of Public Counsel.

“No,” Reynolds answered.

“Or about getting involved in programs?” Rosenbaum asked.

“No,” Reynolds answered.

“Or anything that the VA could offer you?” Rosenbaum asked.

“No,” Reynolds answered.

“Did you see any sort of program or system to inform veterans of these wars as to what the VA could do for them?” Rosenbaum asked.

“I didn’t,” Reynolds answered.

He recalled going to the VA campus and being told “to go to the homeless veteran welcome center the next day.”

“And I was like, why am I going to a homeless veteran welcome center? I shouldn’t be homeless. I’m here asking for help,” Reynolds testified.

He remembers asking where he could stay that night. “And she said, ‘There’s nowhere you can stay tonight. And you’re going to have issues with your dog. And that’s when I walked out of the hospital, furious.”

Defense attorneys had no questions for Reynolds.

Proceedings for Powers v. McDonough will continue on Wednesday, August 7 at 8:30 a.m.

Wednesday, August 7, 2024

Rob Reynolds journey to a federal courtroom began with him taking pictures of military veterans sleeping on a busy Los Angeles boulevard.

It was during the pandemic, and the Iraq war veteran couldn’t understand why so many of his fellow veterans were sleeping outside on San Vicente Boulevard. Their homelessness bothered him so much he photographed some sleeping and photographed sheriff’s deputies “coming through one time and clearing their stuff away.”

He placed the photos on a poster and took it to a meeting of the Veterans Community Oversight Engagement Board (VCOEB).

“I just couldn’t understand why these veterans were sleeping on the street,” Reynolds testified Wednesday in a federal bench trial in Los Angeles federal court. “I had no idea, really, about the land at that time.”

Reynolds said he asked the VCOEB why all the veterans were out there. After the meeting, fellow veterans approached and told him about a years-old court case and longstanding allegations that the massive veterans hospital property in West LA “is being illegally leased and the VA is not taking care of veterans.”

“And it was just infuriating to think that something like that could happen,” Reynolds said.

Reynolds returned to the witness stand Wednesday morning after testifying Tuesday about the horrors he experienced in Iraq and the problems he experienced when he returned home. His testimony Wednesday focused on his path from troubled veteran to impassioned advocate with AMVETS. The trial before U.S. District Judge David O. Carter, a U.S. Marine veteran who has a Purple Heart and Bronze Star from the Vietnam War, is to help Carter decide how to proceed after issuing two major orders that say the U.S. Veterans Administration discriminates against veterans who are homeless and eligible for housing built on the VA’s west LA campus because of their disability compensation. The judge said the VA has a fiduciary duty to use its 388-acre campus for housing and health care. The VA currently leases some of the property for sports fields, parking, and oil drilling, among and other uses unrelated to serving veterans.

Reynold testified about learning of the complicated history of legal challenges to the land use, and realizing that he wasn’t alone in his anger.

“During this period of time, did you ever speak with a veteran who thought it was okay in terms of what had been done with respect to the deed?” asked plaintiffs’ lawyer Mark Rosenbaum of Public Counsel.

“No, I never did,” Reynolds testified. “Every veteran that I met was very upset by what was going on and wanted to do anything they could to help fix it.”

Reynold said he came to know the phrase “Veterans Row” to refer to “San Vicente Boulevard outside the gates of the West LA VA where veterans had been sleeping and dying for years waiting to get into the VA.”

Reynolds recalled attending a town hall meeting with other veterans in early 2020. He said a VA official conceded, “You know what? Maybe we haven’t been doing things correctly out there, and we’d like to help.”

But what happened after that only seemed to be part of the problem.

The VA allowed veterans “to set up tents inside the VA,” but the VA didn’t provide them, the Brentwood School, which leases some of the campus property, did.

“I never went inside because they were too small to go inside,” Reynolds testified. “We had veterans in wheelchairs and walkers that were physically unable to get down on their hands and knees and crawl into the tent.”

“Was there room inside those tents for the belongings of those veterans?” Rosenbaum asked.

“No,” Reynolds answered.

There also weren’t real bathrooms, only portable toilets.

“The veterans with disabilities could hardly even stay in those tents because of how small they were,” Reynolds said.

Reynolds said another veteran “offered to donate large 10×14 tents to the VA for their new program they were creating, and the VA turned down those donations.”

“Over this period of time, did you observe any insects or rodents around the tents?” Rosenbaum asked.

“That was always an issue, yes,” Reynolds answered.

“Did the veterans talk to you about the rodents and the insects?” Rosenbaum asked.

“The big thing that they ever talked to me about is how they wanted to get into the VA or they wanted to stay on the VA, but they couldn’t live in these child-sized pup tents,” Reynolds answered.

“At this period of time, Mr. Reynolds, was there any available permanent supportive housing on the VA grounds?” Rosenbaum asked.

“No, and there was none under construction,” Reynolds answered.

Reynolds said he saw veterans get turned way from the VA hospital and have mental breakdowns on San Vicente Boulevard.

“I had veterans run out into traffic. I had veterans talk about wanting to commit suicide,” Reynolds testified.

Rosenbaum asked Reynolds if he believes the approach “was an adequate solution to veteran homelessness?”

“No, I think permanent, supportive housing is an adequate solution to their own homelessness,” Reynolds answered.

Reynolds recalled meeting with VA Secretary Denis Richard McDonough when he visited Los Angeles in 2021.

“He didn’t answer me on the issues with the leases, but with the same-day shelter and permanent supportive housing. He said, ‘We’ll work on it,’” Reynolds said.

Reynolds also testified about sheds on the VA campus that currently house veterans.

“Do you know if there are veterans currently in those sheds who want to be in permanent supportive housing?” Rosenbaum asked.

“Yes,” Reynolds answered.

“How do you know that?” Rosenbaum asked.

“I speak with veterans, and I’ve never met a veteran that doesn’t want to be in some type of permanent supportive housing or want something better for themselves,” he said.

Reynolds testified he believes the policy that classifies veterans disability compensation as income needs to change.

“There’s no reason that that should deny them from getting into housing close to the hospital,” Reynolds testified.

Thursday, August 8, 2024

The first witness on day three in the bench trial over the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs’ approach to housing at the West Los Angeles VA campus was Ben Henwood, a professor at the University of Southern California’s Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work. Henwood was hired by the plaintiffs to study the role permanent supportive housing can play in helping homeless veterans, broadly, as well as how it functions at the VA.

He testified that permanent supportive housing “is highly effective at reducing homelessness” among veterans. However, the VA’s program “is not as effective as other forms of supportive housing.”

Henwood said a key factor in effectiveness is “accessibility, and accessibility can be facilitated by having services that are close by.”

“Permanent Supportive Housing is used throughout the country to address homelessness,” he testified.

Henwood was followed by Jefferey Powers, the lawsuit’s named plaintiff and a 62-year-old U.S. Navy veteran. He testified he was discharged from the service after he and his bunkmate became lovers, which at the time got them both discharged.

Powers testified about becoming homeless and seeking help from the West LA VA in summer 2020. He stayed in a tent on campus and said it was “like living in a tool shed.”

Powers said the “constant bombardment” against his mental health was “horrible.”

“I watched so many veterans just slide into a dark, deep pit, and many of them didn’t come out,” he testified of his time living on the VA campus grounds. “It’s so very sad, and even today, the conditions that go on there are deplorable.”

Powers testified about being kicked out of campus and being told by VA police that he’d threatened a social worker, which he denies. He was admitted to a psychiatric ward “and then for the next three days, I was constantly interrogated about what had happened.”

After Powers testified, DOJ attorney Brad Rosenberg, who did not have any questions in the cross-examination, thanked him for his Navy service. “I did want to take a moment to acknowledge your service on behalf of the United States,” Rosenberg said. “I know that it was shorter than what you would have liked, but here in this courtroom, on the record and on behalf of the United States, thank you for your service.”

Following Powers’ testimony, the plaintiffs called Sally Hammitt, who is chief of the Community Engagement and Reintegration Services Program for the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System. Before moving to LA, she worked in homeless-related programs for the VA in Cincinnati.

When plaintiff’s lawyer Tommy Du of Robins Kaplan LLP asked if the VA’s goal “on average” is one caseworker for every 25 veterans, Hammitt said “it’s a little bit more complicated than that.” She agreed that if case workers had lower case loads, they would have more time for their cases, “Certainly that would give more time,” she said, “and that would depend on the needs of each veteran that we’re serving.”

“Ms. Hammitt, you would agree with me that meeting your staff involved is critical in the fight to house homeless veterans?” asked Du.

“I would agree with you,” she said.

Du then showed data from 2022 that showed staffing levels at what Hammitt said was “90 percent of the goal.” It increased through the year, but ultimately the VA still didn’t meet its staffing goal.

Hammitt said the staffing “looks a lot higher now.”

She said she wants to ensure the data that Du showed her is updated “because it will show some significant improvements.”

Asked about the 2022 Master Plan that calls for 1,200 units of permanent, supportive housing on the West VA LA campus, Hammtit said, “I definitely don’t think 1,200 units are sufficient.”

“We would need more to house every veteran,” she said.

Hammitt described the “housing first” approach to homelessness as believing that every person has a fundamental right to housing.

“We believe that we should conduct our work with compassion and really place the person in the center of everything that we do,” she testified.

Hammitt also said people aren’t generally homeless because of drug and alcohol addiction.

“Largely, people are homeless due to the shortage of affordable housing,” she said.

Friday, August 9, 2024

Deputy Medical Center Director John Kuhn took the stand Friday, the trial’s fourth day, and fielded a volley of questions from plaintiffs about his oversight of the VA campus, available services and housing units and the campus’ Master Plan.

The exchange became testy at times with Judge David Carter weighing in on one line of questioning in which he threatened Kuhn, plaintiffs and the defense with a weekend sojourn to distant housing units that are available to veterans.

Kuhn’s testimony came after Sally Hammitt, chief of Community Engagement and Reintegration Service (CERS), continued her testimony from Thursday. Questioned by the defense, Hammitt explained the organizational structure of CERS, the programs and employees she oversees and the goals and outcomes of each program.

Kuhn arrived at the VA in Los Angeles in the fall of 2022, having previously served as the first director of Supportive Services for Veteran Families.

The plaintiffs’ counsel inquired as to some of the programs he had implemented during his time in Los Angeles, such as a hotline homeless veterans can call to receive immediate, temporary housing.

“The idea behind the hotline was we wanted to establish same-day access for veterans who were unsheltered,” Kuhn said. “The most dangerous place for a veteran is on the street. There are significant mortality, morbidity risks for veterans on the street.”

Kuhn touted the hotline as helping get many veterans off the street. Call volumes were “quite high,” he said, adding that they have since “dropped off.”

Questioning turned to the Master Plan which calls for an additional 1,200 beds to be added to the campus.

“And is it the first job the first job of VA… to get veterans off the streets?” asked plaintiffs counsel Roman Silberfeld.

“It is,” Kuhn said.

“And you read the Master Plan as addressing those issues?” Silberfeld asked.

“It is a partial effort to address those issues because it was never meant to be the entire effort,” Kuhn replied.

Silberfeld pressed on with the line of questions, asking if Kuhn believed the Master Plan would not have a “robust impact” on veteran homelessness.

“No, it would have the impact it needs to have,” Kuhn said. “The Master Plan is not designed to end homelessness in Los Angeles. It’s designed to have a contribution to that goal.”

Kuhn was then asked to address the low volume of housing referrals made by the VA to Los Angeles area housing authorities and if those issues were due to low staffing rates.

Silberfeld noted that in 2023, the average weekly referral rate was four.

“It’s not that now,” Kuhn said.

Kuhn added that although staffing was part of the issue, veterans’ difficulties using vouchers, stringent housing requirements and housing availability also contributed.

“I appreciate the answer,” Silberfeld said. “That entire answer, though, Mr. Kuhn is about the utilization of vouchers, not about whether VA is doing its job to refer homeless veterans to the housing agencies. Can we agree about that?”

“I agree that we would like to make more referrals for vouchers, certainly,” Kuhn said.

Silberfeld continued to press Kuhn regarding staffing vacancies and whether they contributed to veterans churning out of housing.

“I’ll make an admission right now that may speed things up,” Kuhn interjected. “When I arrived we did not have enough staff. We had a choice to either continue placements, knowing services would not be adequate, or say to our veterans that ‘We’re not going to place you because we don’t have adequate services.’”

During the examination, Kuhn was also asked about areas of the West LA campus that are leased to UCLA and the Brentwood School for athletic facilities.

“Do you believe that the use of the baseball stadium by UCLA has, as its predominant focus, the provision of services to veterans,” Silberfeld asked.

“I do not,” replied Kuhn.

Regarding the lease by the Brentwood School, which includes rent and providing in-kind services such as the use of athletic facilities and transportation services for veterans, Kuhn was candid.

“I don’t want to defend the in-kind contributions,” Kuhn said, “but the logic behind it is they’re giving above and beyond what’s required.”

Even without the in-kind contributions, Kuhn explained, the Brentwood School would still be meeting their contractual obligations. And Kuhn noted that the VA would be responsible for maintaining the land if the Brentwood School did not occupy it. (Silberman countered that the VA would then have the use of the acreage.)

“That said, no, it does not primarily benefit veterans,” Kuhn said.

Later, as Kuhn was testifying about an off-campus Veterans Affairs Supportive Housing unit located in Templeton, more than 200 miles north of LA, the defense objected to the use of a LAHSA website to obtain vacancy data.

Judge Carter said the information could be “easily” verified or “called into question.”

“Do you feel like driving a little bit,” Carter asked the defense counsel. “Think very carefully about this, because you’re about to verify this for the court this weekend.”

Carter said he would also order a plaintiff counsel to also attend to make it “co-equal.”

“Let’s bear down on you: Is this one of your off-site locations that you refer veterans to?” Carter asked.

“It is, but-,” Kuhn started.

“Is this accurate information or not?” Carter asked.

“It should be-,” Kuhn said.

“No, not should be. Is it accurate information or not?” Carter asked.

Kuhn ultimately agreed to have his staff verify the information on the website by Monday and left the stand temporarily to make a phone call “so I can instruct my staff to get working on this.”

Near the end of Kuhn’s testimony, Carter addressed HUD’s sudden decision on Wednesday to discontinue its policy of considering veterans’ disability benefits as income, making some veterans ineligible for housing assistance. The previous policy was a major tenet of the lawsuit.

Kuhn acknowledged the development.

We have to wait for the formal guidance to come to the public housing authorities, Kuhn said, adding that he hopes the guidance to come quickly.

“Before this trial ends,” Carter asked, smiling.

But Carter also noted that the decision may not be adequate for the plaintiffs, and that he may still have to make a ruling. “Why don’t we just leave this on the table without further input by me?” he said.

Monday, August 12, 2024

An earthquake roiled the First Street U.S. Courthouse in downtown Los Angeles, Monday, shaking up proceedings in Powers v. McDonough, a lawsuit brought by disabled veterans suing the department of Veterans Affairs for access to housing.

The magnitude 4.4 tremor is not the first time a quake hit veterans fighting for housing in LA. At least 46 of the more than 60 people who died in 1971’s San Fernando earthquake were veterans at the VA’s Sylmar facility. Ultimately, the disaster lead to the eviction of all veterans living at the West LA VA, resulting in today’s ongoing unhoused veterans crisis. For more on how that natural disaster changed the fate of generations of veterans, read “The Land War.” Part Three of Home of the Brave.

The trial’s fifth day began with the conclusion of testimony by Deputy Medical Center John Kuhn and the start of examination of former Medical Center Director Steven Braverman. Kuhn began the trial’s day by being examined by the defense counsel, touching on the decline in veteran homelessness in the City of Los Angeles since he assumed his position at the Greater Los Angeles VA.

When Kuhn arrived in Los Angeles in 2022, there were about 4,000 homeless veterans in the city, he said. In 2024, there were 2,991 homeless veterans in the city, according to a point-in-time count conducted by the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority. “I think it demonstrates that the innovations and the approach we’re taking in Los Angeles have an effect,” he said.

On cross-examination from plaintiff’s counsel Roman Silberfeld, he acknowledged however that “we can’t determine direct causality.”

Kuhn also detailed some of his efforts to add to the permanent housing inventory available to veterans including at sites off of the West LA campus “The campus is certainly an important feature of our ability to place veterans in housing,” he said. “We have the ground, there’s a lot of undeveloped area on the grounds, and the opportunity to build housing is being taken advantage of. But we also need to build housing throughout the community; it cannot just be in West LA.”

“Many veterans don’t want to live in West LA,” he added. “They don’t want to live in a hospital. They want to live in the community.”

Kuhn said there was “danger in messaging that the place to live, if you’re a homeless veteran, is the West VA campus.”

Kuhn also expressed skepticism about the “demand” for the volume of new permanent housing units at the West LA campus called for by the Master Plan (1,200) and some experts (2,800). “From a demand perspective, it’s not evident to me that that’s necessary,” he said, referring to the point in time count.

Kuhn also said the construction of an additional 1,000 units of temporary housing on the campus called for by some experts “would be a fantastic waste of resources.”

“Why would we spend funds on something that’s not going to solve homelessness,” Kuhn said, stating that across the VA of Greater Los Angeles service area, there are approximately 300 open beds per night.

Judge Carter asked Kuhn how many open beds there are nightly on campus. Kuhn answered that there are approximately 35.

Silberfeld challenged Kuhn regarding the need for temporary housing.

“Mr. Kuhn, if something isn’t done to create temporary housing on campus, veterans on the street will die, isn’t that true,” Silberman asked.

“No, that’s not true,” Kuhn answered. “We have sufficient temporary housing to get veterans off the street. Getting them to accept the temporary housing is a greater challenge.”

Following the conclusion of Kuhn’s testimony, Steven Braverman took the stand. Braverman served as the director of the Medical Center until 2023 when he became Network Director for the VA’s Desert Pacific Healthcare network which includes the systems of Greater Los Angeles, New Mexico, Long Beach, and others.

“You would agree, would you not, that those (homeless) encampments are not conducive to good health, correct,” asked plaintiff’s counsel Mark Rosenbaum.

“I would say that… in general, it’s not a place that I would want to be,” Braverman said. “But at the same time, there is some comradeship and other things in some of those encampments that people find reduces their stress.”

Rosenbaum then pressed Braverman on his home on the West LA VA campus, one of the two single-family homes on the 388-acre property.

“The reason that you lived on the West LA grounds was so that you could be close to the medical center, isn’t that, right,” Rosenbaum asked.

“Yes,” Braverman answered.

“That house, sir, it’s your understanding that that house was constructed by the VA, isn’t that right?”

“I believe that’s true.”

Braverman also testified about additional on-campus housing units in which members of the medical center’s executive team and other staff members reside.

“These are all on West LA grounds, is that right,” Rosenbaum asked.

“Yes,” Braverman answered.

“There are sidewalks there?”

“Yes,” replied Braverman.

“It’s a little community?” asked Rosenbaum.

“Yes,” said Braverman.

Braverman also answered questions about Building 209 which has been a point of contention for the campus. “(Building) 209 was an existing building that was built by the VA, that was renovated in approximately 2012 or to be used to house veterans in a residential treatment program called compensated work therapy,” he said.

Rosenbaum asked if the renovations to the building were made “for the purpose of providing access to health care.”

“Yes, I think that’s fair to say,” Braverman said.

During Rosenbaum’s questioning of Braverman about HUD’s policy change last week regarding veterans’ disability payments no longer being considered as income for the purposes of housing eligibility, Judge Carter interjected with concerns.

In a release submitted into evidence, HUD encouraged state and local housing authorities to also make coinciding changes, but did not mandate that changes be made.

Braverman said he was optimistic that state and local jurisdictions would make the necessary changes to their rules, thus making them eligible for more affordable housing units.

Carter said he was in an “uncomfortable” position deciding the case while the details of the rule change were still being worked out at the federal and local levels.

“Now I’m going to ask you,” Carter said, turning to Braverman, “Do you have any information of any discussion about removing all service-connected disability, or is this going to be some kind of equation… that leaves some people, quite frankly, standing outside in terms of their benefits?”

Braverman answered that he believed all service-connected disability payments would be removed from consideration.

“So sitting here today, you cannot tell Judge Carter with 100 percent certainty that in determining eligibility for unhoused veterans with disabilities for permanent supportive housing — either on the VA grounds or in the community — that they [disability payments] not be counted as income.” Rosenbaum said. “Isn’t that true, sir?”

“I would be shocked if that didn’t come to pass,” Braverman answered.

Tuesday, August 13, 2024

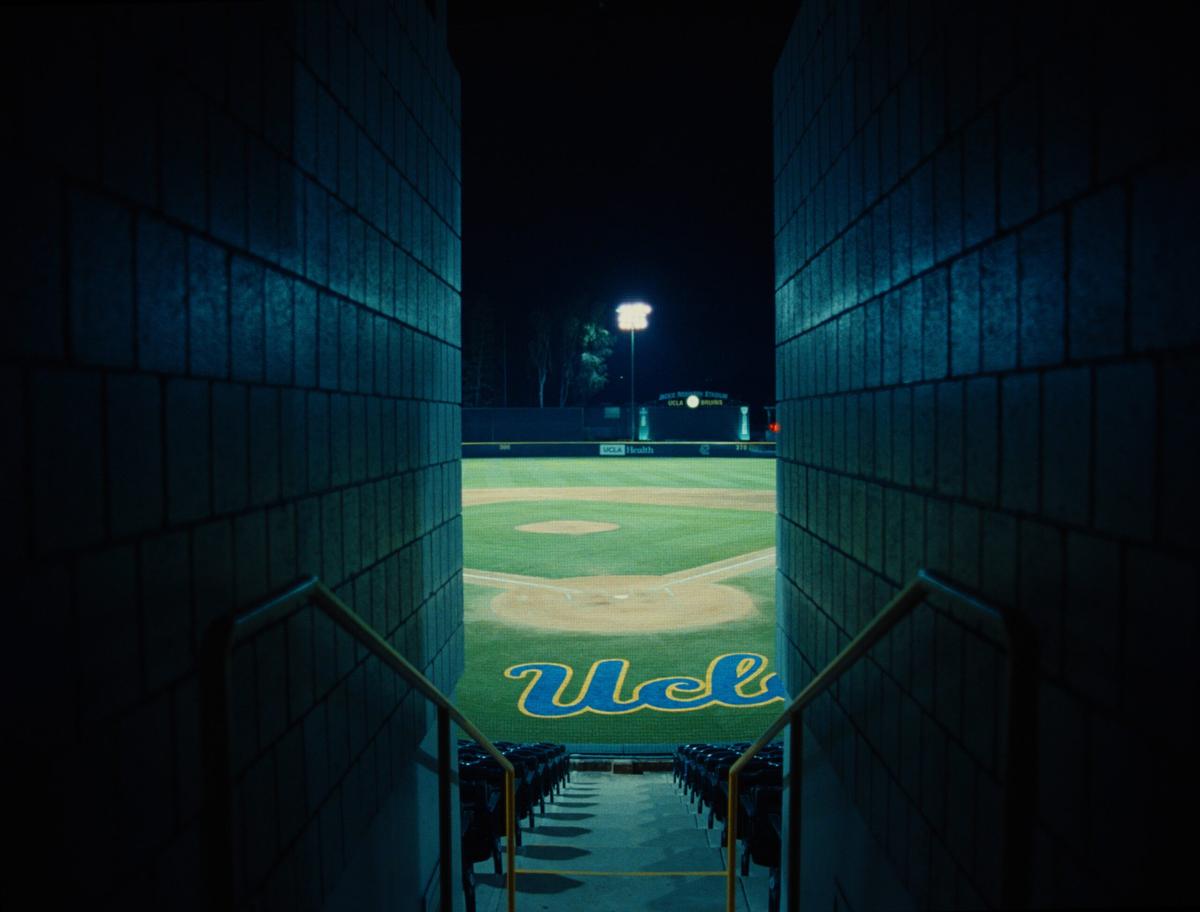

The UCLA baseball complex, situated on roughly ten acres of the VA Greater Los Angeles Medical Center campus, took center stage during the sixth day of the Powers v. McDonough trial, as plaintiffs introduced a recording of VA executives discussing how veterans and advocates would react to the construction of a new practice field on government land. The recording can be heard in “The Promised Land,” a documentary film short that’s a part of Home of the Brave, Long Lead’s multi-part, multimedia feature on the West LA VA.

“Our advocates, who are a little testy out there, are gonna get up in arms when they see that there’s another ball field being built,” Robert McKenrick, former deputy director of the medical center, can be heard saying in the recording.

The audio discussing the construction and opening of the Branca Family practice field at Jackie Robinson Stadium was played during the continued examination of former medical center director Steven Braverman (who was taking the stand for a second day) by plaintiff’s counsel Mark Rosenbaum.

Rosenbaum took aim at the baseball complex, UCLA’s lease, and naming rights to the fields.

This was not the first time the issue of the field has been raised during the trial. On day four, current Deputy Director John Kuhn told the plaintiffs’ counsel that the field “did not principally benefit veterans.”

“You are aware that the West Los Angeles Leasing Act of 2016 requires land use agreements on the property, whether they’re leases or easements or revocable licenses, to principally benefit veterans. Is that correct?” Rosenbaum asked Braverman on Tuesday.

“Yes,” Braverman answered.

Rosenbaum noted that the VA does not have a thorough definition of “principally benefit” and that Braverman had previously characterized the benefits as being “in the eye of the beholder” in a deposition.

Decisions regarding leases and their potential benefits to veterans are made by a committee, Braverman explained. He did not know if veterans were able to give input on those decisions.

In the recording, McKenrick said veterans would not be happy with the announcement of the new practice field and chose to allow UCLA to announce the project.

“I knew that there would be some who would be opposed (to the field),” Braverman said. “I believe it to have been a mistake to have not engaged people more transparently ahead of time, and then just have to justify the rationale for the lease after the fact.”

Rosenbaum also asked Braverman about naming rights for UCLA’s baseball facility, stating that under a federal law, it is illegal for buildings on government land to be named after individuals without congressional approval.

The Jackie Robinson Complex includes facilities named after multiple people, including former Dodger pitcher Ralph Branca. Rosenbaum also noted that the Branca family had also donated money for the field, around $1 million per a news report referenced by Braverman.

“You never asked for that number, whatever this total is, to be turned over to the VA for the use of veterans, isn’t that right?” Rosenbaum asked.

“I did not ask for that money to come to the VA,” Braverman said. He also testified that he wrote a letter to UCLA stating that the naming of the facility was illegal and improper but did not insist that the name be removed.

Questioning then turned to the Brentwood School, which leases 22 acres of the VA campus upon which it has built an athletic facility.

Two Office of the Inspector General reports from 2018 and 2020 that examined lease agreements with the VA found that the school’s agreements were illegal under the Leasing Act, Braverman said.

Braverman said the VA disagreed with the finding, but that some changes were made to the services, offerings, and donations the school provided in-kind, per the lease agreement.

Rosenbaum also asked Braverman about the fiduciary duties of the VA. The VA, Braverman said, has a fiduciary duty “to make sure we use resources appropriately, and that we identify where those resources should be used. Some of that includes the provision of resources toward housing.”

“Do you believe the VA has a fiduciary duty to provide permanent supportive housing to all unhoused veterans in Los Angeles?” Rosenbaum asked.

“I would say no,” Braverman said.

“You don’t believe that the VA has a fiduciary duty (to house homeless veterans) under the 1888 deed — isn’t that right, sir?”

“Judge Carter has found that we do, and I’m not a lawyer associated with that. That wasn’t the position of the VA prior to this trial.”

During questioning by defense counsel, Braverman described some of the issues homeless veterans on Veterans Row had faced getting access to shelter on the campus.

“In that time, when I first arrived at VA, I would say that there were people who were reluctant, there were people who were distrustful, there were people who felt like they had been abandoned or weren’t being provided the care that they needed,” Braverman said. “And there were others who were looking to try to get access to that care.”

The VA has a policy that did not allow homeless encampments on campus, Braverman said.

Other veterans encountered issues involving sobriety requirements, smoking restrictions and pet restrictions (some of which have been loosened).

When the COVID pandemic began, Braverman helped implement a program to allow people to bring their tents onto the campus, but declined a donation of 25 large tents due to size concerns. (For more on this, read “The Old Guard and the New Fight,” Part Five of Home of the Brave.) Braverman called the decision a mistake. As a result, the large tents were set up on Veterans Row.

Eventually the large tents were allowed on campus, and the success of that initiative led to the placing of the tiny shelters which were purchased by the VA, Braverman said.

The line of questioning aroused Judge Carter.

“Why were you able to purchase tiny shelters, but you can’t construct long term support housing?” Carter asked. “Who’s making that decision?”

“The interpretation—,” Braverman said.

“No, not the interpretation. Who’s making that decision?” Carter asked. “I keep asking for a written document. I’m going to assume there is none unless I see it.”

Braverman returns to the stand on Wednesday for a third day of testimony.

Wednesday, August 14, 2024

Another school athletic facility located on the West Los Angeles Veterans Affairs campus drew significant attention on the seventh day of testimony in Powers v. McDonough, a day after the plaintiffs took aim at UCLA’s baseball field.

Questioned by the defense counsel, former Medical Center Director Steven Braverman, taking the stand for a third consecutive day, defended the VA’s lease agreement with the Brentwood School, which operates an athletic complex on 22 acres of the West LA VA campus.

The complex includes football and baseball fields, a pool, a basketball court and other amenities which veterans may use during selected hours. The school also provides “in-kind contributions” like maintenance to the buildings and facilities, food donations to veterans, a shuttle service, and scholarships to the school for children of veterans.

“We don’t have the funds for a shuttle service, for example, that is allowed to shuttle people who are not eligible for beneficiary travel,” Braverman said. “But the Brentwood School can do that on the campus, which has been beneficial.”

Braverman acknowledged that the lease was found to be out of compliance with leasing laws by the VA’s Office of the Inspector General because it does not principally benefit veterans.

“(The OIG says) it could be terminated or resolved, but they won’t tell us how to resolve it, and that’s part of the challenge,” Braverman said. “I believe it could be improved.”

“Do you believe that the costs to the VA, of terminating the Brentwood School lease, would be greater than the benefits that the VA currently receives from that?” asked defense counsel.

“Yes,” answered Braverman.

Later in the day, questioned again by Mark Rosenbaum, Braverman again said the OIG would not tell the VA “what it would take to be in compliance.”

“The OIG report points out the defects,” Rosenbaum said.

Braverman said that the VA disagreed with the OIG regarding the in-kind contributions.

“…That’s not going to be fixed,” he said.

After asking about the Brentwood lease, the defense moved back to the lease with UCLA and asked Braverman if the VA could knock down Jackie Robinson Stadium if the lease were terminated.

It might be considered a historical site but I don’t know for a fact, Braverman said.

Judge Carter interjected and noted that the original American Legion stadium had been demolished before the construction of the newer facility, which was opened in 1981.

“How is that a historical site?” Carter asked.

“It could be an old wives tale,” Braverman said.

Questioning then turned to the overall budget for the VA nationwide, as it pertained to funds available for construction projects.

Braverman testified that “major construction projects” like those at massive medical centers were budgeted at around $2 billion and came out of the VA’s overall budget.

An overhaul of the Greater Los Angeles critical care tower, which includes new emergency and operating rooms, was budgeted for around $1.4 billion.

The defense asked if there there were any other sources of funding. “For major construction that’s really the only source,” Braverman said.

Braverman also testified that the 1,000 units of temporary housing called for in the Master Plan would take up approximately 24 acres.

“What happens if it’s double-storied?” Carter asked.

“It would be less of a land use requirement,” Braverman responded.

“That’s very simple,” Carter said.

Braverman also testified about what he believes are other challenges for a high volume of housing VA land. “One of the challenging issues is the notion that every unhoused veteran needs to be housed on the West LA campus,” he said.

The challenge with having everybody housed in one area puts people at a safety risk, Braverman said.

“We’ve already seen at (buildings) 205, 208, 207, more than a 200% increase in crimes and security calls not only in building areas but across campus,” Braverman said, also noting that the campus police vacancy rate is 47%.

“Not to malign anybody but these are just the statistics,” he added.

The plaintiffs also called Gennifer Yoshimaru, assistant head of the Brentwood School.

Yoshimaru testified that the school (which charges tuition of $45,000 for elementary school students and $53,000 for middle and high school students) had attempted to find an alternate site to house its sports teams after a judge ruled that the sharing agreement between the VA and the school, which allows for the VA to use the sports facilities, was illegal under federal law.

The plaintiff’s counsel noted that the school had retained attorneys after the finding.

“All to the end of getting that law amended?” Rosenbaum asked.

All to the end of continuing our relationship with the VA, Yoshimaru answered.

Rosenbaum repeated the question. The defense objected on the grounds that the question had been asked and answered and was argumentative.

Carter overruled the objection.

“All to the end of getting that law amended?” Rosenbaum asked again.

“Yes,” Yoshimaru answered.

When questioned by the defense, Yoshimaru touted the school’s efforts to be responsive to veteran requests and suggestions.

“Our goal is to outperform the commitments we make,” she said. “We do not want to do the bare minimum.”

When asked by Carter about how the school would handle “volatile veterans” near the school, Yoshimaru said the school entered into the “partnership” with the understanding of who would be served.

Near the close of the day, the plaintiffs called Michael Seeger Dennis, senior program advisor at HUD, to testify.

Dennis testified about some of the barriers to implementation for the rule change proposed by HUD last week that would end veterans’ disability payments from being considered in housing income requirements.

The Department of Treasury, for instance, could not make a coinciding change regarding eligibility requirements for homes and apartments built using low-incoming housing tax credits.

“Nothing prevents HUD from retracting this policy change tomorrow, does it,” asked plaintiffs attorney Amanda Mangaser Savage.

“No,” Dennis answered.

Thursday, August 15, 2024

Dueling interpretations of the VA’s ability to construct housing on the West Los Angeles campus were featured in court Thursday as Powers v. McDonough entered its eighth trial day.

The plaintiffs called to the stand C. Brett Simms, executive director of the VA’s Office of Asset Enterprise Management.

Simms explained that he oversees capital budget requests for VA’s construction projects, its Enhanced-Use Lease program and its real property. Jasper Craven interviewed Simms and John Kuhn during his reporting for Home of the Brave and published the conversation as a Q&A prior to the start of the trial.

After summarizing Simms’ responsibilities and purviews, plaintiff’s counsel Roman Silberfeld asked Simms about the VA’s authority to construct permanent supportive housing.

Silberfeld asked Simms about clauses in the 2016 West Los Angeles Leasing Act which state that the VA secretary “may carry out” “any enhanced-use lease of real property… for purposes of providing supportive housing, as that term is defined in section 8161(3) of such title, that principally benefit veterans and their families.”

Simms stated that according to the interpretation of the law by Robert Davenport, chief counsel of the VA’s real property law group, “that is the only method to deliver housing.” Earlier in the week, Steven Braverman, director of the VA’s Desert Pacific Healthcare Network, had invoked Davenport’s interpretation during his testimony.

Judge David Carter asked Simms if it was written anywhere.

“It would be in the enhanced use lease policy,” Simms answered.

“My question, fundamentally, is are there other ways in which the VA can build permanent supportive housing, other than through the enhanced use lease (law)?” Silberman asked.

“I do not believe there are,” Simms said.

Silberfeld noted that the VA had renovated Building 209, a residential building, using its own funds and authority.

Simms answered that the project had “explicit consent” to be built as part of the Compensated Work Therapy program in which veterans live in building 209 but work jobs both on campus and off.

“It was not general-purpose housing,” Simms said.

“I’m not saying it was,” Silberfeld said.

Silberfeld also asked Simms about the domiciliary located at the VA Greater Los Angeles, a residential facility for substance abuse treatment.

“The domiciliary was created by the VA, using its funds, not an enhanced use lease, correct,” Silberfeld asked.

“Correct,” Simms answered. Silberfeld then asked how that was accomplished using VA funds, not an enhanced use lease.

“The domiciliary is explicitly listed as a type of medical facility that we can build with our programs,” Simms answered.

Later during questioning, Silberfeld asked if Davenport ever cited to Simms any other statute or policy or rule that justifies the position that the VA cannot build permanent supportive housing.

The defense objected on the grounds of attorney-client privilege. Carter overruled the objection.

We always focused on congressional intent, Simms answered. “Congressional intent and their policy direction to us was very clear that the EUL program is how (housing) should be delivered,” he said.

Prior to Simms’ testimony, the court heard continued testimony from Michael Seeger Dennis, senior program advisor at HUD.

Questioned by the plaintiffs, Dennis reiterated that although HUD no longer considers veterans’ disability payments as income for the purposes of housing eligibility, issues still remain with Treasury Department policies.

According to a VA study, only 3% of applicants did not meet income requirements for the HUD-VASH (Veterans Affairs Supported Housing) voucher program.

Dennis said the “real problem” is housing built with low-income housing tax credits, which have their own income eligibility requirements set by the Treasury Department.

In yesterday’s testimony, Dennis testified about barriers to implementing HUD’s proposed rule change. For example, the HUD policy — because it’s a federal rule — wouldn’t impact income requirements on state and locally financed housing that require income restrictions, which means disability payments could still block veterans from being eligible for housing.

After Dennis was dismissed, the plaintiffs called Jonathan Sherin, a psychiatrist with a Ph.D in neurobiology who worked at the West LA VA starting in 2003 as a staff psychiatrist, and eventually became the facility’s chief of psychiatry and mental health programs. He has experience in advocacy and specialized knowledge in homelessness — particularly among veterans — as well as mental health and addiction.

Sherin served as a special consultant in the Valentini settlement, and he helped develop the 2016 Master Plan. The big idea is to create an intentional community, he said. The Master Plan would help create not only housing units but a place with a range of other resources (medical, emotional, career, financial) where even veterans from outside the campus could congregate, he added.

But Sherin also acknowledged the importance of housing. “Housing is definitely a heath care issue for me,” he said. “Homelessness is deeply traumatic.”

Being homeless for any period of time presents stressors to veterans, Sherin said. “These stressors, en masse, generate a serious amount of mental illness.”

Sherin was critical of the government’s response to veteran homelessness. “Speed of response has been entirely inadequate,” he said. “And the breadth has been narrowed so that the intentional community has been modified into a housing project.”

“I do worry that just housing without anything to do is a setup for bad outcomes,” Sherin said. Nonetheless, he said something should be done to house veterans immediately.

“Veterans in who are homeless in Southern California need housing today they need it now,” Sherin said.

Carter weighed in on Sherin’s testimony. “The VA has a problem and it’s called Congress,” he told Sherin.

They, Carter said gesturing to the defense table, can’t go to Congress with an idea. “They need dollars and cents,” he said.

Carter advised Sherin and the VA to negotiate what “a reasonable figure” of housing units might be. “You can’t just walk in and say we want 10,000 — you’re dead on arrival,” he said.

But Carter seemed to express support for Sherin’s philosophy for a reimagined GLA campus. “Is there any better therapy than a veteran talking to another veteran?” Carter asked.

“No,” Sherin said.

“Therefore if you’ve got a community of other veterans you’ve got the best therapy?”

Sherin agreed.

As the day drew to a close, however, Carter expressed much less enthusiasm for a settlement between plaintiffs and Bridgeland, which operates a drill site on the campus, that is a co-defendant in the Powers v. McDonough suit.

The settlement would see Bridgeland increasing the royalty payments on its gross revenue up to 5 percent, paying it to an entity jointly designated by Plaintiffs and VA. Bridgeland would also grant back a 1 1/2-acre parcel of land adjacent to its drill site back to the VA for the express purpose of housing, a Bridgeland attorney explained. The drill site would still be operational.

Carter was incredulous. “Why would I put long-term supportive housing next to an oil well especially if I have people (veterans) who are involved with burn pits, asthma, and Agent Orange?” he asked.

“I’m not going to pre-judge this but, whoa,” he said, addressing both the Bridgeland attorney and Silberfeld. “You want an initial impression? I’ll put it on the record: Whoa.”

Wednesday, August 21, 2024

Before the sky even hinted at dawn on the ninth day of proceedings in Powers v. McDonough, Judge David O. Carter walked briskly around the athletic facilities of the Brentwood School, which have been a major point of contention in the trial.

The facilities, including the school’s pool, football and baseball fields, and tennis courts were the first stops on a walking tour of the West Los Angeles Veterans Affairs campus that started before 5 a.m. on Wednesday and did not end until late morning.

Carter, dressed in jeans, running shoes, a loose button-down shirt, and a United States Marine Corps baseball cap, stalked across the pool deck surrounded and followed by more than a dozen people, including plaintiffs’ counsel Roman Silberfeld and Department of Justice attorney Brad Rosenberg, veterans advocate Rob Reynolds, the judge’s clerks, and several reporters.

As Carter left the pool facility, walking past the ivy-covered walls of the school, he headed to the nearby softball and baseball fields. The outfields of the two parks adjoin each other, creating a wide open expanse of lush grass. He walked from one end of the field to the other, at times pausing to look out at the expanse. Occasionally, he would make a quick turn one way and a quick turn another as the entourage sometimes struggled to keep up. At times he would take off his cap and use it to gesture at an area or facility before jamming it back on his head and walking.

At the fields, Carter could be heard conversing with Silberfeld and Rosenberg asking them to overlay the layouts of buildings 205, 208, and 209, recently renovated housing units, onto the fields.

“What does that look like here?” he asked.

Walking off of the Brentwood School property, Carter led the cadre to Veterans Barrington Park, athletic fields and a dog park on VA land leased by the City of Los Angeles.

The fields were pockmarked with gopher holes and appeared much less maintained than the Brentwood School’s green spaces.

Carter examined the field before continuing on his tour of the campus, walking the hilly terrain to the east side of the campus where the Bridgeland oil well sits, adjacent to the 405 Freeway.

The week prior, the judge had previously expressed concern over a potential settlement between Bridgeland and the plaintiffs that would see over an acre of site given over to the VA for housing (or potentially a parking lot).

On Wednesday, Carter stood with his back to the freeway and marked off approximately 500 feet. I’m not building next to a freeway, he said.

The next stop was the UCLA baseball complex which includes Jackie Robinson Stadium and the Branca Family practice field, also on VA land. Carter surveyed the area from the top of the grandstands and moved down to an adjacent parking lot and to nearby gardens which were overgrown. Abutting the area leading to the gardens is a neighborhood of large single-family homes separated from the VA campus by a fence. Carter asked Silberman to demarcate a “setback” a few hundred yards from the fence separating the area and the homes as if he were surveying for a potential building.

Despite the rising temperatures as the sun rose in the sky, Carter continued on his tour walking next to some of the campus’ residential buildings. He waved in some of the journalists to view the buildings and an empty unit. “You’re the taxpayers, it’s yours,” he said.

The tour continued on as the judge walked from one point of interest to another, from the dilapidated Wadsworth Chapel, where Carter and members of the group were required to don hard hats, masks, and bright yellow vests, to CTRS, a group of ‘tiny homes’ installed on the campus near where Veterans Row once lined San Vicente Boulevard.

Carter did not want to see only landmarks and buildings and tended fields — on one occasion he led the group through an undeveloped parcel of land shaded by trees with a heavy layer of foliage on the ground.

As the tour came to a close, after several miles and over five hours, he thanked Silberfeld, Rosenberg, Reynolds, and the VA staff for inviting him to tour the campus.

“I never would have gotten this from a map,” he said.

Back in the courtroom, the plaintiffs called Steve Soboroff, who has, among other duties, served as the LAPD commissioner and the president of the LA Recreations and Parks Commission. He has also played a role in several major Los Angeles developments including the Staples Center (now called the Crypto.com Arena) and, notably, the neighborhood of Playa Vista which saw the development and construction of thousands of housing units.

Soboroff testified about the need for housing on the VA campus calling the homelessness crisis “an American tragedy” and denigrating the “tiny shelters” as looking like toilets. “Except they don’t have toilets,” he said.

Soboroff expounded on a report he had prepared for the plaintiffs to place up to 1,000 units of temporary housing on the campus. He had identified six parcels where the housing could go, how much could be placed on each parcel, and the types of homes that could be built. Regarding one slide which showed an example of temporary homes Soboroff offered: “Give us 18 months from tomorrow… and that will be there.”

The defense challenged Soboroff on his rosy timeline, presenting him with testimony he had given in a deposition showing that he did not know about the National Environmental Policy Act which requires federal agencies to undertake impact assessments prior to making decisions.

But much of Soboroff’s questioning came from Carter who drilled down the proposed sites for temporary housing and some of the issues they presented. On multiple parcels, Carter asked about the potential issues that would arise from residents and homeowners. They’d be NIMBYs, Soboroff said.

On another parcel where there currently is a lot open to veterans to sleep in their cars overnight, Carter asked why it should be removed to make way for housing. Low utilization, Soborhoff offered.

Carter pressed, asking how many cars use the lot per night. “I have a feeling no one really knows,” Carter said.

What also drew Carter’s attention were not the parcels Soboroff had selected for housing but the ones he had not, namely the Brentwood School, UCLA’s baseball field, and Veterans Barrington Park, which he noted “the city supposedly maintains it but if you walk it, it’s as poorly maintained as possible.”

Soboroff countered that removing a city park would create a firestorm of political blowback. “I think there’s more of a firestorm from homeowners and renters,” Carter replied.

Thursday, August 22, 2024

Questions surrounding UCLA baseball’s Jackie Robinson Field led off the tenth day of the Powers v. McDonough trial, a day after Judge David Carter and attorneys toured the site on the West LA VA campus.

The plaintiffs called Tony DeFrancesco, executive director of the veterans affairs relations and programs for UCLA and liaison between the VA and the school.

While on the stand, plaintiffs’ counsel Mark Rosenbaum asked DeFrancesco about the terms of UCLA’s lease with the VA, pointing out that, among other issues, the school was paying well below market rate for its lease.

DeFrancesco did not offer any defenses of the lease practices and Rosenbaum noted his commitment to the veterans at the VA.

I’ve been serving vets my whole career, DeFrancesco noted.

“I think it’s obvious you care deeply about veterans,” Rosenbaum said.

The Rosenbaum asked bluntly if he thought that the baseball stadium did not principally serve veterans.

“Yes,” DeFrancesco answered.

“And that’s always been the case?” Rosenbaum asked.

“I believe so,” DeFrancesco said.

Before leaving the stand, Carter thanked DeFrancesco for his “candidness.”

“I understand how uncomfortable it is,” Carter said. “I wish the UCLA athletics director were here answering these questions.”

The plaintiffs’ counsel Roman Silberfeld next called real estate developer Randy Johnson, who had worked with Steve Soboroff in Playa Vista. Like Soboroff, Johnson had been retained by plaintiffs to strategize on how to place units of temporary housing on the campus. “My parameter is how do you get it done and the steps to get it done,” he said. “I’ve been looking at what is possible to do.”

As he did with Soboroff, Carter again poked at some of the granular details and issues with some of the sites identified as potential temporary and permanent housing locations. Regarding one site proposed by Soboroff and Johnson adjacent to the 405 Freeway, Carter again said that he would not build housing within 500 feet of the roadway.

“That’s not a restriction I was aware of,” Johnson said.

“That’s a restriction I’m placing on you,” Carter answered.

Carter and Johnson discussed housing density (whether three- or four-story structures would be feasible or necessary), costs (Johnson said the total would be a “big number” around $1 billion), and possible financing vehicles.

Carter expressed a distaste for four-story structures.

In selecting sites for temporary housing, if we ignore the UCLA and Brentwood School areas — which the judge noted in the prior day’s testimony Soboroff had not considered building on — Carter said, that leads to taller buildings. The judge said he had a hard time understanding why the developers had ignored those possible development sites.

Johnson noted that interruptions of the UCLA and the Brentwood School areas had been avoided in planning for additional housing.

“Why,” Carter asked.

“Litigation,” Johnson said.

The day also saw Carter weigh in on a settlement that had been proposed between Bridgeland oil and the plaintiffs which would have seen the company “quit claim” or turn over a portion of its lease to the VA. Carter said he had “extensive” concerns including issues with possible health risks of building on or around an oil field and close to a freeway.

“We may be running into problems that will make this, frankly, a nightmare,” he said.

Ultimately, Carter did not want to chill attempts at a settlement but inferred that it should be reworked.

For the first time since the early days of the trial, the court heard testimony from veterans who had experienced homelessness but were currently housed on the campus.

Joshua Petitt, an Army veteran who has served from 2002 to 2008, took the stand first. Petitt said he enlisted on Sept. 13, 2001, two days after the 9/11 terror attacks and was deployed on one tour to Iraq in the dangerous Anbar province.

“Americans were dying every day,” Petitt said.

During his 14-month deployment, his battalion took “heavy casualties,” he said. Twenty-six members of the battalion were killed in action while Petitt himself received three Purple Hearts. After returning home, he began suffering from mental health issues that included anger, nightmares and drug abuse.

With one month left until he was due to be discharged, he left the base one weekend to see his newborn daughter.

“I didn’t come back,” he said. “When they did catch me, they charged me with desertion.”

Petitt was ultimately given an honorable discharge but felt that he was ill-equipped to return to civilian life.

Petitt said he had been homeless intermittently since 2011 and struggled with drug abuse, PTSD and other issues.

“It’s like being back in Iraq,” he said of being homeless. “You do things to keep yourself awake and alert.”

Eventually, Petitt made his way to the Greater Los Angeles campus, first living in the tiny shelters and then waiting for one of the renovated buildings to come online.

“I wanted one of those apartments,” he said. “They said, ‘You can’t, you make too much (disability) money.’”

Eventually, after the lawsuit was filed, he obtained an apartment in Building 205 where he lives today.

Why do you want to live near the West LA Campus, plaintiffs counsel asked.

“Because I love my bro-vets,” Josh Petitt said, adding, “It helps with my mental health.”

Lavon Johnson, another Army vet, followed Petitt on the stand. “I’m a little nervous,” Johnson said as he sat in the witness box. “There’s a lot of people.”

Johnson served as an attack helicopter mechanic after enlisting in 2004. He served a 15-month tour in Iraq. “It didn’t even register that I could die one day,” he said of his deployment, during which he suffered a traumatic brain injury.

Johnson said after being discharged he was “immediately homeless” as he struggled to adapt to civilian life. For eight years he was homeless in Texas before he made his way to Los Angeles and the VA where he obtained a HUD-VASH voucher for an apartment 15 miles from the campus, leading to 30-mile round trips for appointments and care.

He called the experience of living away from campus “lonely.”

One day, he said, he left the apartment and “wandered for about a week” before returning to the VA campus and was eventually hospitalized for nearly a year.

Johnson eventually obtained housing in Building 208. “It’s the best thing for me,” he said of living on campus. The community of other veterans “actually get me,” he said.

Asked if the campus needed additional housing Johnson answered, “Yes, yes we do. There are a lot of veterans out there.”

Following Johnson’s testimony, Keith Harris, senior executive homelessness agent for the GLA campus, testified about his role at the campus.

Plaintiff’s attorney Mark Rosenbaum asked Harris about attempts to address the issues facing the GLA campus with VA officials, like Sec. Denis McDonough, White House officials, or other parties.

Friday, August 23, 2024

Housing vouchers, and veterans’ ability to make use of them in Los Angeles, were centered on the 11th day of proceedings in Powers v. McDonough.

Carlos VanNatter, director of Section 8 housing for the Housing Authority of the City of Los Angeles (HACLA), took the stand first and explained to the court the state of the HUD-VASH voucher system in LA. HUD-VASH (Veterans Assisted Supportive Housing) vouchers are allocated to local housing authorities and pay for the rent of homeless veterans up to certain rent thresholds. The thresholds are based on an area’s fair market rent.

There are two types of vouchers: project-based, which are tied to specific properties that serve mainly or only low-income residents, and tenant-based, which can, theoretically, be used by a renter at any rental property that meets certain conditions or criteria.

VanNatter explained that around 4,900 HUD-VASH vouchers were in use in Los Angeles and noted that the program faces several challenges including the rental market and utilization rates.

If a housing agency, such as the HACLA, falls below a certain utilization rate (in which a person is referred to the program and receives a voucher) the agency could lose a portion of its allotment of vouchers. The utilization rate, VanNatter said, depended on the VA referring homeless veterans to the program.

But low referrals from the VA had “persisted” since the start of the program in 2008, VanNatter said, adding that he had met with local VA officials Sally Hammitt and John Kuhn and some national officials to address the issue. It was not the first time the issue had been raised during the trial: HUD official Michael Seeger Dennis testified to referral issues last week.

VanNatter also addressed the issue of attrition in the HUD-VASH program where veterans fall out of housing that had been obtained. In some years, the number of residents lost to attrition had outpaced the number of referrals to the program, VanNatter testified.

Attrition can be caused by various factors like death and “skipping,” when a person leaves the residence without notice, VanNatter explained. But one of the major factors of attrition is “non-compliance” in which a tenant loses housing due to lapses in paperwork or other issues. Non-compliance-based attrition could be addressed with additional case workers, VanNatter said.

During cross-examination from the defense, VanNatter was shown HUD-VASH statistics from the first half of 2024 that seemed to indicate an improvement in the number of referrals made by the VA and in attrition.

“Voucher utilization is a very complex problem,” said Keith Harris, executive homelessness agent for the VA Greater Los Angeles, who continued his testimony from Thursday.

Harris acknowledged issues with attrition and referrals but also detailed that one of the major factors plaguing veterans was the average median income issue at the heart of the lawsuit. He said he has been “flabbergasted” by the AMI issue and has spent much of the last two years attempting to address it.

Harris detailed that for Building 207 on the VA campus, for instance, he had lobbied for the developers to raise the AMI threshold above 30% which they did. But he noted that about half of the units on track to open at the campus were still being built with a 30% AMI restriction.

As had been noted previously in the trial, one of the major hurdles to fully addressing the AMI issue were not only HUD rules, which the agency has proposed changing, but Treasury Department guidelines as well.

Harris testified that last year he made a presentation to a federal advisory committee regarding the issue in which he outlined two main solutions: raise the threshold and remove disability payments from consideration as income.

He said he “became a thorn in the side of other agencies” over the issue with developments, like the HUD rule change, occurring within the past few weeks. Harris also inferred that the Treasury Department was mulling its options in addressing the issue.

At that, Judge David Carter interjected.

“What’s taken a year? Why should this court have any confidence that this (rule change) is going to happen?” Carter asked. “These are going to be some wide-ranging decisions I have to make,” he added.

Two veterans also testified on Friday, speaking about their issues with HUD-VASH program despite its benefits.

Joseph Fields, an Army Artillery veteran who enlisted at 17 years old, spoke about his experiences with homelessness. Afflicted by back problems due to his service as well as his homelessness, he walked to the witness stand bent over at the waist; his torso was all but parallel to the floor. After leaving the Army, Fields said, he had issues “dealing with life on life’s terms.” He struggled with homelessness, spending several years on Veteran’s Row, PTSD, and muscle and joint pain.

Eventually, he applied for the HUD-VASH program but said he had to “fill out the application two or three times” before being successful. Nonetheless, he was elated with his apartment on the West LA VA campus, which he had visited with his grandfather, a Korean War veteran, decades before.

“It’s been 10 years since I had an apartment,” Fields said, his voice breaking. “Hanging out with vets on that property means a lot to me,” he added.

The comradery of veterans was something the second veteran witness to testify, Laurianne Wright, was missing at her HUD-VASH apartment in Lancaster, Calif., which is located 65 miles from the West LA VA campus.

“My depression has gotten really bad,” Wright testified. “I feel isolated. I’m trying to get out of there.”

Wright enlisted in the Army in the 1980s while still in high school. But a few years into her service, while stationed in Italy, she was sexually assaulted by a squad commander. After the incident was investigated, she was honorably discharged.

“I left the military very ashamed… I didn’t do anything wrong,” Wright said. As with Fields, she struggled with PTSD, substance abuse, and homelessness.

Despite being homeless and spending time at places like Veterans Row and the tiny shelters at CTRS, Wright found comfort among other veterans and near the VA campus.

There’s nothing like being able to do a walk-in at the clinic, she said.

Regarding why she had joined the lawsuit as a class representative, Wright said she didn’t want anyone who had reached out for help to suffer.

Taking the podium, a defense counsel thanked Wright for her service. He paused and then, with a shaky voice, commended her for being a survivor.

Monday, August 26, 2024

The 12th day of Powers v. McDonough was focused on process, specifically the process of enhanced-use leases (EULs) on the West LA VA campus.

After the completion of testimony by Keith Harris, the VA’s senior executive homelessness agent for greater Los Angeles who had originally taken the stand beginning on Thursday, the defense called back to the stand C. Brett Simms, executive director of the VA’s Office of Asset Management, who oversees the VA’s real property.

Simms had previously testified in the trial two weeks prior when called by the plaintiffs. During his testimony then, he spoke about the VA’s interpretation of a clause in the 2016 West Los Angeles Leasing Act which dictates how EULs on the West LA VA campus are operated.

According to the VA’s interpretation of the clause, EULs are “the only method to deliver housing,” Simms said on Day 8 of testimony.