Who killed Andre Butler?

He was born on Independence Day, joined the Marines, and died as a disabled man living in a tent on the streets of Los Angeles. But this veteran’s death sentence came long before he set up camp outside a federal property that was founded to house service members like him.

When the cameras start rolling outside the gates of the West Los Angeles Veterans Affairs Medical Center in February 2019, it’s dark and raining. A homeless veteran named Kevin, who has been living on the sidewalk adjacent to the VA campus, squints under the bright light of Fox 11’s broadcast television crew. As he gathers his belongings to shield them from the weather, he tells a reporter that LA police showed up that morning to clear out a group of homeless veterans like him. “They tell us to get out,” he says, lowering his eyes. “Grab whatever personal belongings you have and go.”

The camera cuts to another veteran named Andre Butler. Clad in a black fedora and a matching hooded sweatshirt, Butler, 64, may not look like he’s lived on the streets of Los Angeles for a year, but he has. With a delivery that verges on the dispassionate, he tells the news crew that police sweeps have taken his belongings three times so far. When that happens, the Vietnam vet adds, he just gathers more things and brings them back to this spot.

The camera pans to a makeshift shelter — a pink satin sheet draped over a ring of white boxes — on the sidewalk of San Vicente Boulevard. This wide thoroughfare serves as a western boundary for the 388-acre West LA VA campus, as well as a Main Street of sorts for the well-heeled neighborhood of Brentwood. The news reporter explains that the number of homeless veterans living outside the facility has increased, and sanitation workers sweep encampments every few months in an attempt to “sanitize the area.” Advocates for homeless vets recall police arresting unhoused people around that time who refused to cooperate or turned confrontational.

The news report then turns to Houman Hemmati, a physician who lives nearby and has treated unsheltered patients for free. Hemmati tells the broadcast crew that when other homeless veterans — many of whom use services provided by the VA — found out they wouldn’t be bothered there, the population grew, the sidewalks became blocked, the trash increased, and crime ticked up. But it’s not their fault, he says. The news reporter says Hemmati used to do a rotation at the VA, when it used to do more to help its veterans return to society. “If they’re just roughed up for the day, or just locked up temporarily and then released back on the street, that doesn’t do anyone any good,” Hemmati says. “In fact, it does harm.”

The news brief then cuts back to the row of veterans on the sidewalk, where the camera captures Butler in the background, gaunt in his jeans, poring over his belongings. Though a sweep had occurred earlier that day, items sprawl across the concrete and pile against the metal fence of the VA campus. A shopping cart holding more objects sits in the foreground. Because Kevin and Andre are waiting for services from the VA, the narrator explains, they plan to return to San Vicente Boulevard tonight. More sweeps won’t change that.

The news segment ends with Butler, without flinching, telling the reporter, “I’m not gonna quit until the last breath is in my body.” Two and a half years later, while still searching for a permanent place to rest his head, Butler will die just feet away from where he says those words.

In death, there’s a tendency to paint someone as either a sinner or a saint, wicked or virtuous, but life is rarely that simple. Like most people, Butler lived somewhere in-between. Ask his family and friends and they will tell you he served his country with honor, worked his tail off as a manual laborer on public projects, and selflessly came to the aid of those around him. Yet they’ll also say Butler committed a raft of crimes large and small, did hard drugs on Los Angeles street corners, and had a short fuse, violent tendencies, and a penchant for vengeance that could make him a real pain in the ass at times and downright scary at others.

For all his virtues and vices, though, the facts, are these: Andre Maurice Butler was born July 4, 1954, became a Marine, and some 50 years later, sick and disabled, lived and died alongside other unhoused veterans in a makeshift camp outside the West LA VA that became known as “Veterans Row.” Put another way, the baby who shared a birthday with the United States of America lived — and ultimately died — on its streets. Worse, he suffered this fate mere steps outside a property given to the federal government more than 136 years ago to house veterans just like him. But over the last 50 years, that property’s stewards have been perpetually unable to accomplish this mission.

Lavon Johnson is a disabled Army veteran who served in Iraq and lived two tents over from Butler on Veterans Row. Three decades Johnson’s senior, Butler was in Johnson’s arms as he took some of his last breaths. Talking about the experience years later still makes the younger man’s forceful voice quiver. Butler was “extremely giving” to others in need, Johnson recalls, even as the Marine’s own outlook darkened.

“He was in his underwear in the gutter for two weeks straight but never asked for help,” Johnson says. “It wasn’t pride. His legs and arms had gotten stiff. He had given up. He manifested death.”

ALWAYS A MARINE

To begin to understand Pvt. Andre Maurice Butler, you must leave Los Angeles and fly about 2,000 miles to Ohio, where he and his five siblings — Gregory and Donna, who are older, and Kenneth, Carla, and Ronald, who are younger — were born.

It’s a rainy spring afternoon in the Cleveland suburb of Maple Heights, but rays of soft sunshine stream through Carla Butler’s window. Gospel music wafts in from the kitchen, and the sweet aroma of tea, fresh ginger, and lemon slices permeates the room, which is covered with photos of family and friends. A decorative sign reads, “Worry ends where faith begins.”

Carla flutters around the house looking for the photos of her brother Andre that aren’t already on view. At the dining room table sits youngest brother Ronald — for whom Carla is, at 62, a full-time caretaker after a long career as a nurse. Her plump tabby cat, Miracle, weaves around the table’s legs.

Wearing a shirt that says “blessed,” Carla occasionally pauses to harmonize with the gospel melodies. “He used to play the keyboards and I’d sing Chaka Khan and Anita Baker,” Carla says of Andre. “He could play any day. He had a good ear for music.”

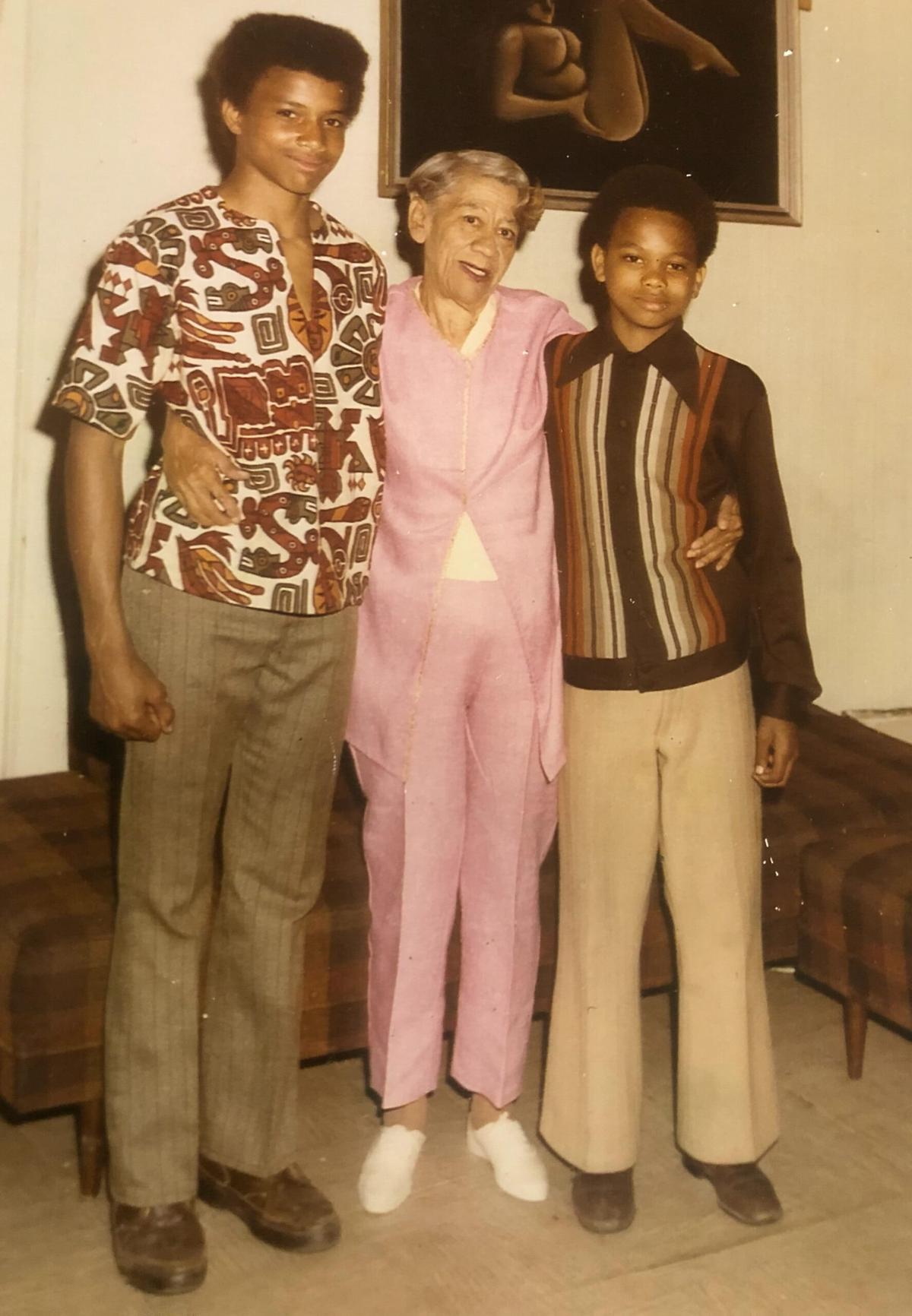

Carla sifts through a plastic tub of photos. There are hundreds of images before her, but she’s looking for something specific. Before long, a familiar face in the pile prompts her to smile. She has found what she was searching for. “That’s my brother,” she says. “That’s Dre.” She kisses the photo.

Andre didn’t have an easy childhood. He grew up in the foster care system, and his siblings say he grappled with feelings of abandonment — feelings that stayed with him throughout his life.

“Andre had some anger issues,” says Greg, who shared a foster home with Andre and their sister, Donna. “When we were younger, he always seemed to be angry. When we walked down the street and somebody looked at him wrong, he would get upset at the person. And it was always somebody bigger than us. So we would be running away or fighting, one or the other. And it was like, ‘Andre, quit starting these fights — we’re not winning the fights.’”

Still, Greg and his other siblings remember that Andre excelled in school and had a healthy repertoire of hobbies. He liked listening to and playing music, playing chess, and tinkering with cars. Andre attended a prestigious all-boys school in Cleveland, where he became known for his mechanical aptitude and love of fixing things. In his softer moments, he lent a hand to family and friends who needed favors, such as a car repair.

According to VA records, Andre enlisted in the Marine Corps three days after his 19th birthday on July 7, 1973, and three months after the last U.S. military unit came home from Vietnam. “Andre was a tough guy. He was into martial arts when he was young,” his cousin Renée Stoudemire recalls. “Andre was very proud of the fact that he was a Marine. Once a Marine, always a Marine. I was married to one — I know the spiel.” His time with the armed forces was short; the VA reports it ended on July 30, 1974.

Instead of returning to Ohio, he settled in Los Angeles, where his biological mother lived. Some siblings, including Donna and Carla, plus cousin Stoudemire, spent periods of their lives in California around that time, often living with Andre during their stays.

In the late 1970s and through the 1980s, Andre had some stability and lived the California dream. He earned wages from a union construction job, rode a motorcycle, and bought a townhouse in the San Fernando Valley, says Carla. “He worked hard,” she remembers.

For a time, he had a casting-director girlfriend who placed several family members in roles as extras in movies and television shows, such as Matlock and Quantum Leap, though he wasn’t much interested in being on camera himself. “Andre would take me to work on set and would watch my children in the evenings for me,” Stoudemire says.

But Andre’s mean and devious streaks punctuated that era. Court records show he was convicted of robbery in 1978, and his sisters, along with his former girlfriend and some extended female family members, recall him having violent outbursts and mental health episodes that left them alarmed and often fearful. “Ain’t nobody wanted to be around him except his mamma,” Carla says. “I couldn’t stand him. He was so mean.”

Then came the accident. One day in 1991 or 1992 — no one can quite remember — Andre was operating a heavy construction vehicle, grading the job site, when the soil gave way under his rig. The impact of the accident tossed him out of his seat, leaving his face lacerated. Over the coming years, Andre was in and out of the hospital as he endured multiple rounds of plastic surgery.

The wounds healed but the scars never went away. Andre was disfigured, and he frequently took painkillers, Carla says. “You can be all right if your leg is broke, but we’re talking about your face,” she adds. The incident and its aftermath took a toll on Andre’s life. “He liked working and couldn’t,” Carla says. “He was always in the hospital.”

Andre left his construction job in 1993, though he continued to hustle for side jobs. “Andre always had him some money ’cause he always knew how to do something,” Carla says.

Court records show police arrested Andre in 1994 for disturbing the peace after he got into an argument with the proprietor of an Inglewood laundromat. When they took him into custody, officers discovered two “cloned” mobile phones — handsets reprogrammed to use someone else’s legitimate service — in his possession. As a result, Andre was charged with two felony counts for receipt of an access card with the intent to defraud, and two misdemeanors for possession of an instrument with the intent to avoid a lawful telephone charge. He was convicted and sentenced to four years in prison for the crimes — double what it would have been otherwise because of his robbery conviction 16 years prior.

Andre was behind bars when his mother died of a stroke in late 1994. “He was mad because his mama died while he was in there,” Carla says. “And we was mad at him, too.”

A LIFE UNRAVELED

When you’ve gotten in trouble, there are facts you tell your lawyers, secrets you tell your friends, and stories you tell your family. Then there’s the rest — the stuff you tell no one.

There is so much we don’t know about Andre Butler’s life after he got out of prison in the late 1990s. When he died outside the West LA VA in September 2021, much of that story went with him. But here’s what is known:

The new convictions on Andre’s criminal record meant “he couldn’t get a loan with nobody,” Carla says. He also began using. For much of his adult life, Andre hadn’t been much of a drinker and limited his recreational drug use to marijuana, Stoudemire says. But by the late 1990s, “He would stand on Cedros [Avenue] with a person we knew and do drugs,” Carla says. “He’d hook up with the wrong folks. He started smoking cocaine then.”

Bit by bit, Andre’s life unraveled as he served periods of jail time on a variety of charges. Along the way, he fashioned himself into a jailhouse lawyer. In 1998, representing himself while in Pleasant Valley State Prison in Coalinga, California, Andre tried, unsuccessfully, to get his conviction overturned. In 2000, while serving a new five-year sentence for petty theft of goods from an LA grocery store, he filed a civil rights complaint against the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department for assault and denial of medical care while in custody. Four years later, he was awarded a $10,000 judgment for it. In 2002, while still in custody, Andre filed another complaint, this one alleging that corrections officers failed to prevent a prison riot that resulted in him “sustaining injuries to his knees, elbows, and hands.” It was dismissed on procedural grounds.

As he entered his 50s, Andre’s legal efforts didn’t slow down. In 2008 Andre — again incarcerated, first at North Kern State Prison in Delano, California, then at High Desert State Prison in Susanville, California — joined a class action lawsuit alleging discrimination against people with disabilities in the Los Angeles County jail system. It was settled seven years later with various changes stipulated and $2.2 million in legal fees awarded. Butler and six fellow plaintiffs were given $2,000 each. In 2008, Andre also filed another civil rights complaint, this one against the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. It was dismissed the following year. In 2013, Andre filed to get an earlier conviction for arson overturned. The judgment was related to a dispute over a shelter in a homeless camp, and Butler’s appeal was denied in 2014.

Meanwhile, with each new conviction and prison sentence, Andre’s mental and physical condition deteriorated. In supporting documentation for his legal claims, physicians diagnosed Andre with a mountain of health issues, including schizoaffective disorder, amphetamine dependence, colon cancer, and arthritis. Family members also recall an esophageal surgery for acid reflux and at least one stroke that altered his speech and left him confined to a wheelchair. In legal filings, Andre’s own descriptions of his conditions included eroding vision, mental instability, indigence, and “excruciating” mobility ailments. “Left side weakness and arthritis makes walking with a cane painful and unbearable,” he wrote on an accommodation request form for disabled inmates signed Sept. 18, 2008. “If I am expected to leave and travel around on a cane it just won’t do.” He took an array of prescription medications for his maladies.

In addition to health problems, Andre also grappled with housing insecurity. At some point he relied on a supportive housing program jointly run by the VA and the Department of Housing and Urban Development known as HUD-VASH. As the once-strapping Marine approached federal retirement age, but before he was allowed to take Social Security benefits, family members say he lost his last real home — likely by eviction for nonpayment of rent and/or drug use, Stoudemire says. (VA says Andre was never evicted from HUD-VASH housing.) “He had some income but he was using it on the streets,” she says. “Once he lost that house, everything really went downhill.”

Carla looks at it differently. “Andre lost everything and just kept starting over,” she says. “I guess the older you get, the more tired you get of starting over.”

But Andre hadn’t given up, not yet. As he sought relief from his myriad health issues at the West LA VA, he also waited for the facility to help him obtain ever-elusive Los Angeles-area housing.

The odds, however, were stacked against him.

THE HOME FRONT

Compared to other U.S. metropolitan areas, Los Angeles is home to more unsheltered people than all but New York City. Yet LA is far and away home to more unhoused veterans than any other American metro area.

There were 3,878 veterans experiencing homelessness in Los Angeles County amid a total homeless population of 75,518 in 2023, according to estimates by the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority. The accuracy of the count is a frequent source of debate.

A casual observer might assume Southern California’s 280 or so days of warm sun per year drives LA’s housing insecurity crisis. It doesn’t. Others point to mental illness, drug addiction, or simple poverty. But most rigorous studies on homelessness in the region reveal a wholly different cause: a dearth of affordable housing.

Veterans experience homelessness at a disproportionately high rate compared to the rest of the nation’s population, regardless of where they live. But LA is an all-American outlier for unhoused veterans at a time when the national population of homeless vets was cut in half between 2009 and 2023, according to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s 2023 assessment of the issue.

In theory, the VA’s sprawling facility in West LA should be sufficient to solve the problem. After all, if nearby UCLA can house 14,500 undergraduates on its 419-acre campus in well-off Westwood, why can’t the VA house 3,900 vets on 388 acres in tony Brentwood?

Historically, there’s certainly precedent. What we now call the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs is a combination of several precursor institutions established by law to provide returning service members both support, in the form of land grants or pensions, and shelter, via a National Asylum — later Home — for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, established in 1865. The VA’s foundational mission to provide veterans with support after they serve remains steadfast today. What has changed, though, is the agency’s scope of that support. A 1958 federal law restructured the VA and eliminated the Soldiers Home system. Since then, the VA has prioritized healthcare over housing. As the agency’s website states: “No longer would the VA be authorized to construct and manage permanent housing for veterans, but instead the agency’s focus narrowed to providing health care, benefits, and cemetery services to veterans.”

There’s also historical precedent to house veterans on the West LA VA campus, specifically. Once known as the Sawtelle Veterans Home and the Pacific Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, the campus was donated to the government in the late 19th century with the express purpose of housing military veterans — and it did, peaking at about 5,000 residents around the time of the Korean War. But the agency’s mid-20th century restructuring led the VA to stop accepting new long-term residents on the West LA campus in the 1960s in favor of providing medical and social services intended to help veterans reintegrate with society.

Since that time, the population and cost of living in metropolitan Los Angeles has skyrocketed. In the five counties that make up Greater Los Angeles, the population grew from almost 7.8 million people in 1960 to 18.6 million in 2020, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Household incomes and housing inventory have not kept pace. Since 1975, the earliest year for which government data are available, single-family homes in the LA metro area have risen 1.2 times faster than in California and 2.5 times faster than the rest of the country. In Los Angeles County today, median household income is $83,411 but the median price of a home is more than 10 times that. In the 21st century, housing insecurity is far and away the No. 1 political issue in the Southland, as locals call it. No one — neither veterans nor civilians — can escape the extraordinary cost of living in L.A, even as its population growth rate has slowed, from 29% from 1960 to 1970 to 4.3% from 2010 to 2020.

As the city surrounding the West LA VA campus grew ever denser — about 122,000 people now live in the three Los Angeles neighborhoods that border the VA campus, more than double the entire city’s population when the VA land was donated — careful observers started to ask questions. Such as why a relatively empty plot of land gifted to veterans stopped housing them. And why parts of a federal campus were instead leased out to private interests. And, most egregiously, why homeless and disabled veterans like Andre Butler were later living on the sidewalk outside the gates of the West LA VA, in view of land pledged to house them, as they waited for housing services that clearly weren’t coming.

Unhoused veterans have long howled about this neglect. A decade before Butler’s 2021 death, in 2011, the American Civil Liberties Union filed a class action lawsuit against VA Secretary Eric Shinseki and the director of the VA’s Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System on behalf of homeless veterans with severe disabilities. Valentini v. Shinseki contended that the VA’s benefits program discriminated against veterans by not providing them with access to the health services to which they were entitled because they were without permanent shelter as a result of their severe mental disabilities. It also claimed the VA misused its campus by leasing parts of it out to third parties that had nothing to do with the mission of providing services and support to veterans.

In 2013, the court ruled the VA’s private leases violated federal law and voided them. A 2015 agreement between the parties stipulated that the VA would create a new master plan for its West LA campus that would include appropriate levels of veteran housing.

But in 2018, unhoused veterans, including Andre Butler, still lived outside, rather than inside, the West LA VA. Two years after that, the encampment on San Vicente Boulevard had grown and matured to the point where it had become Veterans Row — a neat line, sharp as a military crease, of spacious tents pitched on the sidewalk and adorned with large, crisp, level American flags. This is where Butler lived out his final days as one of more than four dozen vets living “on the line,” waiting for promised VA housing somewhere, sometime in the distant future.

“No Veteran should experience homelessness in this country they swore to defend,” says VA Press Secretary Terrence Hays in a statement, “and VA is laser focused on ending Veteran homelessness — in Los Angeles and across America.”

SHELTER SKELTER

That the onset of Veterans Row followed the outbreak of COVID-19 was no coincidence. Following Centers for Disease Control guidance issued in March 2020, Los Angeles County suspended encampment cleanups — the kind Andre Butler had described when interviewed by television reporters in 2019 — that would have forced homeless people to pack up and move their tents. This allowed Veterans Row to gradually grow to include about 50 unhoused veterans of the Vietnam, Gulf, Iraq, and Afghanistan wars, many of whom received services inside the West LA VA campus.

As COVID-19 spread, the population of Veterans Row grew — a conspicuous result of the VA, like so many other organizations during the pandemic, reducing services to adhere to social-distancing guidelines. Hours shortened. Staff became less available. Waitlists lengthened. The VA relied on contracted service providers and nonprofits to fill in gaps. Many unhoused veterans, unable to acquire reliable transportation to the campus during the pandemic, simply moved to San Vicente Boulevard, where a community commiserated and survived together.

In April 2020, the VA announced the Care, Treatment, and Rehabilitative Services program. CTRS, as it’s known, is a “low-barrier-to-entry outreach program” intended to quickly get veterans off the street and onto West LA VA grounds. It promised to provide homeless veterans with a designated tented living area on campus and regular access to medical, behavioral health, and housing services. In theory, CTRS would address the bulging population living on Veterans Row.

But with VA staffing and services stretched thin due to the pandemic, some veterans initially found themselves unable to access the support CTRS provided. Additionally, restrictions on tent size and location on the VA campus meant veterans were limited to using compact “pup tents” — good only for lying down and sleeping — pitched on the hot asphalt of a parking lot and particularly inhospitable to vets with physical disabilities. According to one advocate who was trying to help the vets get housing services, the VA limited its hours, so those seeking a tent on campus after 2 p.m. were denied entry.

As a result of these barriers, many veterans lived in larger tents on Veterans Row, on the perimeter of the campus. That strip of sidewalk was exposed to the dangers of vehicles traveling along San Vicente Boulevard.

Like Butler, Iraq war veteran Robert Reynolds sought services and treatment at the West LA VA. Frustrated with his experience, the former U.S. Army specialist and infantryman dedicated himself to advocating for unhoused veterans and today advises AMVETS, a congressionally chartered veterans service organization. “Los Angeles is still the nation’s capital for veteran homelessness, and it’s absolutely unacceptable,” Reynolds, standing on Veterans Row, told an interviewer in July 2021. “The VA is more concerned with their real estate business and leasing out the [West LA VA] property, always making these promises that they’re going to use the revenue from the leases to go to build housing, but it never happens.”

Months later, the VA changed tack and announced a new initiative to dovetail with its initial CTRS push. In addition to providing services, the VA said it would issue licenses for private donors to place 60 to 70 “tiny shelters” — 8 feet by 8 feet structures equipped with a bed, air conditioning and heating, electricity, and fire safety equipment — on the lawn. The agency also said it would work with county officials to sweep the sidewalk along San Vicente and place unhoused veterans inside campus gates. One way or another, Veterans Row would be no more.

“A stable, clean, and safe living environment colocated with behavioral and medical health care helps to improve outcomes for veterans who participate in these VA programs,” said Dr. Steven Braverman, director of the VA’s Greater LA Healthcare System, in a statement when the program was announced on September 30, 2021.

But for Butler, this news came two weeks too late.

A FINAL SALUTE

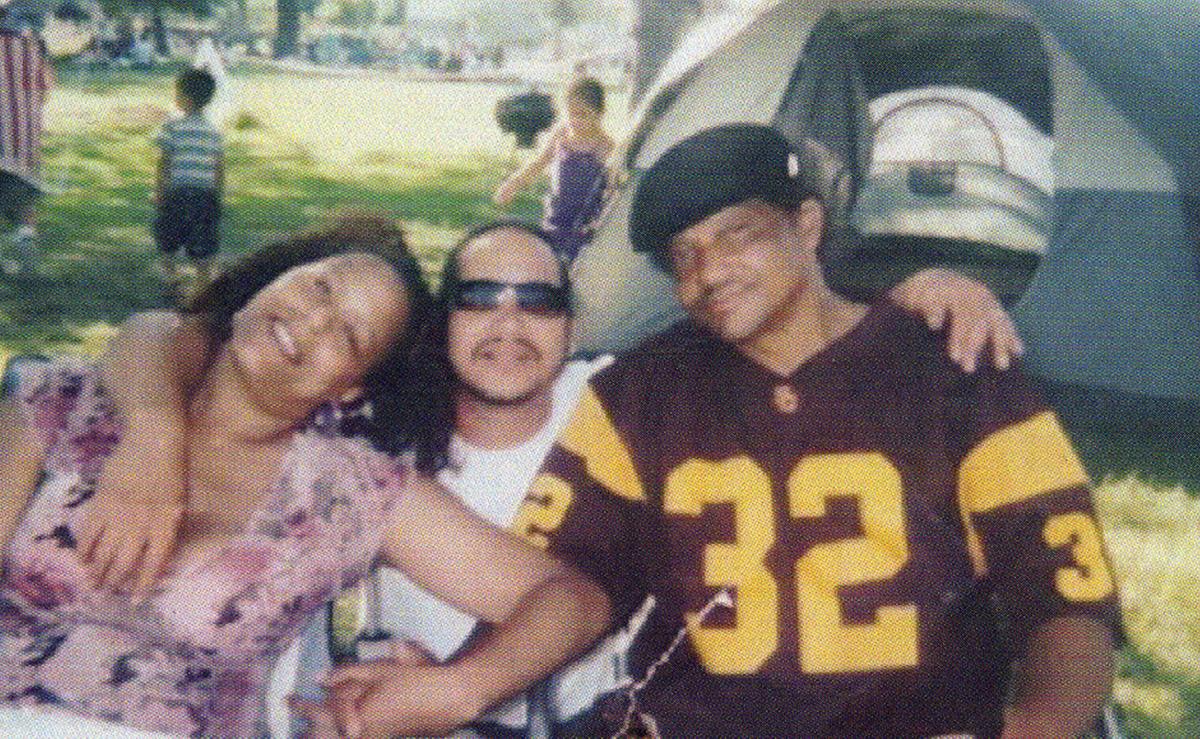

Toward the end of Andre’s life, Stoudemire says, friends and family visited him on San Vicente Boulevard. Age had softened his harder edges. He was kind, generous, and always willing to help others, even as he was relegated to a wheelchair following a bout of muscle weakness that may have been triggered by a highly rare reaction to a COVID-19 vaccine shot, his family says.

“He was always pretty mellow,” says Reynolds, who came to know Andre well in 2021 and remembers specific times when Andre would help to keep the area clean and safe, despite not being ambulatory. “He would stand his ground if people said anything to him, but he was not aggressive.”

Andre required numerous services from the VA, including occupational therapy. But when it came to housing, Stoudemire says the VA “dragged its feet” in finding him accommodations of any kind, including temporary shelter. Johnson says Andre repeatedly requested housing from the VA, to no avail. “He gave a lot, a whole lot, and didn’t receive what he deserved,” the Army veteran says.

No one knows this better than Reynolds. Since he first encountered Veterans Row, he has tracked encampments, organized veterans, and corresponded with VA staff and housing coordinators to get unhoused veterans into both temporary and permanent housing.

While Veterans Row was an active encampment, Reynolds took detailed notes. One on Andre, written in May 2021 — four months before the Marine’s death, reads:

“He is paralyzed from the waist down, has minimal mobility in his arms and hands, and cannot push his wheelchair. I told the staff that he needs to be inside because we can’t take care of him…. He was immobile and unable to go to the bathroom by himself in a tent until Friday, April 30, 2021, when he was transported back to the VA hospital. He is gravely disabled and needs to be inside with assisted living. Living in a tent is a death sentence for him.”

Sister Carla last saw Andre three days before he died, through a FaceTime call. “He was trying to get forgiveness from everybody,” she says. “You know when you’re gonna die — he probably knew.”

They reminisced about happier times when they’d make music together. Andre told his sister he had written some songs. She asked him to send them to her so she could sing them. He said he loved her and appreciated her. “That last conversation was really intense,” she says. “It was like he was saying farewell.”

“Andre’s in a better place,” she adds, solemnly. “He knew the Lord.”

IN THE LINE OF FIRE

In the spring of 2021, two incidents left the Veterans Row community shaken.

The first happened shortly after midnight in early March when a black SUV drove through several tents before crashing into the metal fence that encloses the VA campus. Three people, including the driver, were injured, but miraculously no one was killed.

Soon after that collision, Bryan Prentiss, a 51-year-old veteran, arrived at the encampment hoping to find a place to shelter. Reynolds helped to get Prentiss registered and tested for COVID so he could enter New Directions, a shelter program started by a Vietnam veteran decades earlier. On the Friday before Easter, Prentiss was told he could enter the program the following Monday.

Just after midnight on Easter Sunday, an altercation erupted on Veterans Row. In the scuffle, a mentally ill homeless man drove into the veterans, striking Prentiss and dragging him hundreds of feet. Prentiss died in the street. Another veteran in his mid-30s named Darby Sandoval sustained two broken legs from the incident. Sandoval’s legs healed, and he soon returned to Veterans Row, but the event left him traumatized.

Less than six months later, Sandoval was involved in a third Veterans Row tragedy.

On September 15, 2021 — two weeks before the VA unveiled its plan to move the vets from tent shelters to the tiny homes — Lavon Johnson woke up to screams. The Army veteran burst out of his tent and saw a commotion in the street. People were running around, losing their heads, he says.

It was overcast and humid. Johnson was confused. Before nodding off, he had been on night watch along the line, and it had been quiet.

Then, he says, he saw Andre Butler’s limp figure. A man Johnson didn’t immediately recognize jumped off Butler’s body and walked away.

Pulse racing, Johnson rushed over to his neighbor. Butler was still breathing — barely. “He said, ‘I’m going to die,’” Johnson recalls. A piece of metal was sticking out of the back of the older man’s skull. He had stab wounds around his ear, neck, chest, and arm.

Butler’s body started shaking. Or was it Johnson’s? Butler struggled to take another breath, Johnson says. Paramedics rushed him to Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center, barely a mile away. He didn’t make it. “It didn’t register that Andre had died,” Johnson says. “I was getting hysterical.”

Johnson had found Butler’s body near Sandoval’s tent. That’s when Johnson realized the man he hadn’t recognized amid the pandemonium was Sandoval. “I knew who to be angry at,” he says.

Both Johnson and Reynolds knew Sandoval had been particularly unstable leading up to that night. A day earlier, social workers and police had called Reynolds, asking him to come to the encampment to calm Sandoval, who was “screaming, yelling and flipping out” in his tent, Reynolds says. Sandoval eventually calmed down, the police left, and Reynolds headed home for the night.

According to news reports and recounts from veterans, Sandoval became agitated again during the night. Butler heard Sandoval fighting with his girlfriend, so he rolled out of his tent in his wheelchair and tried to intervene, but Sandoval then turned on Butler, allegedly stabbing him 12 times, killing him.

Furious and panicked, Johnson set out to find Sandoval, racing down the street. But the suspect had already been taken into custody. Other veterans searched for Sandoval’s girlfriend, who they already resented as a troublemaker, believing that she instigated the incident. But the police had already escorted her away. Sandoval’s criminal proceedings are currently suspended while he seeks restoration treatment.

“Nobody could believe what had happened,” Johnson says. “It was all a dream. Nobody was really saying anything. Just crying.”

Andre was gone.

Andre was gone.

A FINAL RESTING PLACE

Veterans receive a number of benefits from Veterans Affairs for serving in the U.S. military. Barring extraordinary circumstances, most service members receive some or all of them; even incarcerated vets can still be eligible. Of the many types of military discharge, only “dishonorable” — issued as punishment for the worst offenses and representing less than one-tenth of one percent of the U.S. armed forces — fully disqualifies a vet from VA programs.

The VA offers dozens of veteran benefits. Some are widely recognized by the average American, including the GI Bill; a military pension; primary medical, dental, and prescription drug coverage for veterans injured or sickened because of their service; various grants, loans, and insurance policies; and counseling for things like substance abuse, or career advancement. A handful of career, health, and housing services — such as rental assistance vouchers — target unhoused or at-risk vets.

Alongside general government relief like Social Security, many residents of CTRS and Veterans Row, as Andre Butler did, receive a mix of benefits and services from the West LA VA. Proximity to the sprawling medical campus is one reason their encampment formed on the sidewalk outside its gates — an irony since the hospital was first built there to care for and house the disabled Union soldiers from the Civil War.

VA benefits don’t end when a veteran dies. Eligible vets receive a gravesite in any national cemetery with available space; the opening, closing, and perpetual care of that grave; a government headstone or marker; a burial flag; and a Presidential Memorial Certificate — “The U.S. honors the memory of…” at no cost to their families.

In a populous place like Los Angeles, “available space” can prove a challenge. Some 90,000 veterans have been buried in the Los Angeles National Cemetery, first opened in 1889 and located east of the West LA VA campus, separated by Interstate 405. The 114-acre burial grounds were closed to interments in 1976 (with the exception of family members of those already buried there) and closed to cremation interments in 1998. But in 2019, the cemetery added a columbarium on 13 acres on the western edge of the freeway, closest to the VA, to house the cremated remains of almost 91,000 more veterans and their family members.

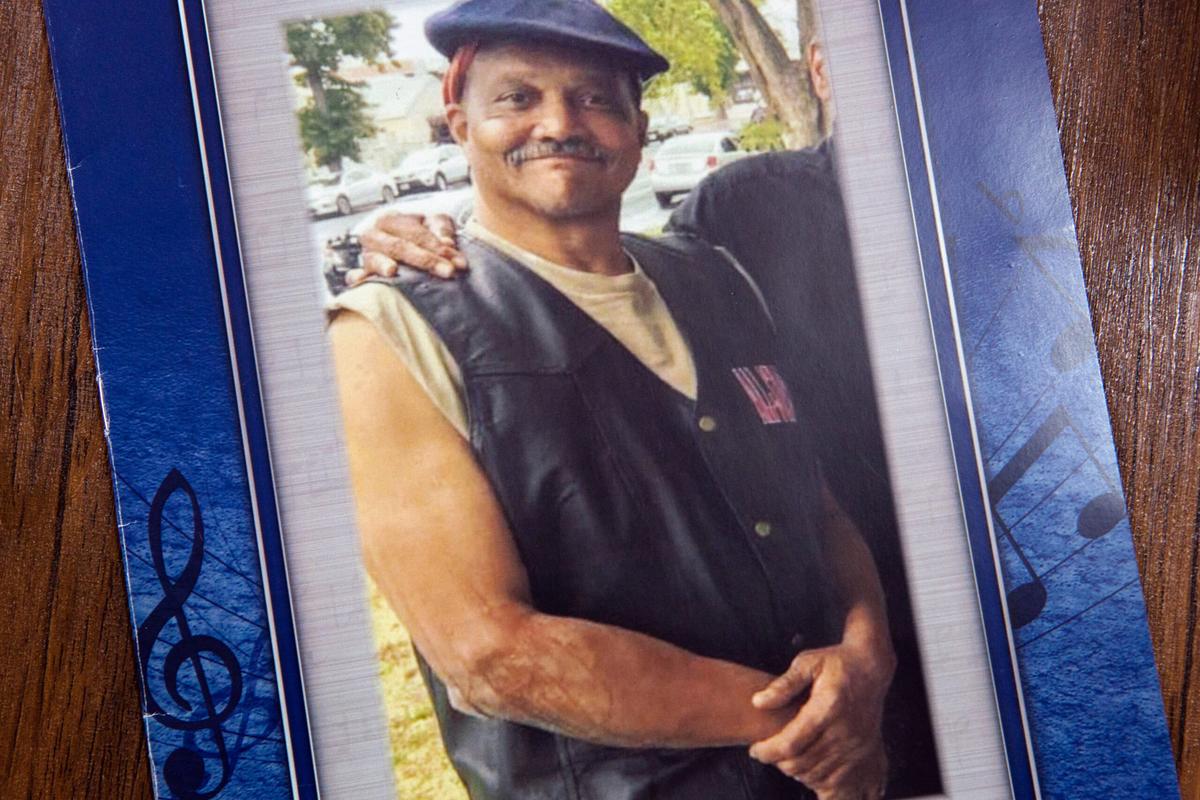

The 2019 dedication event for the columbarium, held on a cloudless and sunny LA day, was a celebratory affair. “In keeping with the cemetery’s proximity to Hollywood,” a VA press release noted, the ceremony featured a red carpet, a large suspended American flag, and remarks by VA Secretary Robert Wilkie, actor Gary Sinise, and Congressman (and Air Force vet) Ted Lieu. Along the opposite side of the VA campus, about a half-mile from this star-studded affair, lived unhoused and disabled veterans, including Andre Butler.

Butler is not honored at the Los Angeles National Cemetery, despite having lived for years right outside it. To find his grave from the West LA VA, you must drive south to make your way to the freeway, then drive west — into the congested, frenetic heart of Los Angeles, then right back out of it — for almost 80 miles. Sandwiched between sprawling Amazon fulfillment warehouses and March Air Reserve Base, and under a sweeping sky punctuated by palm trees, is Riverside National Cemetery. At more than 1,200 acres, this final resting place is the largest and busiest military cemetery in the U.S. — more than 10 times the size of the Los Angeles National Cemetery and twice the size of Arlington outside Washington, D.C., albeit with fewer graves to date.

Tyron Seaborn, Stoudemire’s brother, remembers the wake for his older cousin Andre. It was a modest affair — several of Andre Butler’s immediate siblings were unable to attend for health reasons, and the drive from central LA is more than two hours of smoggy gridlock. Still, a smattering of family loved ones made the trip for the reception and funeral, which included the customary military honors. “It was heartbreaking to see my cousin lying there,” says Seaborn, who works for U.S.Vets, a nonprofit organization committed to, among other things, ending veteran homelessness in the U.S.

Past the winding entrance and beyond Eisenhower Circle, just off Korea Avenue, Pvt. Andre Maurice Butler’s modest grave marker sits among hundreds arranged in neat lines, sharp as a military crease. Adorned with a Christian cross, the stone is Butler’s final, enduring VA benefit for the service he provided to his country. His middle name, carved into the granite, is misspelled.

With additional reporting by Emily Barone, Jon Peltz and Sarah Rogers.

GET UPDATES FROM THE FRONT

Follow the veterans’ fight for housing at the West LA VA and receive court briefings from the trial.