The Land War

After a deadly earthquake and a flood of broken promises, Los Angeles veterans brought the fight to their own government, launching a 50-year battle for housing that’s still raging today.

In the morning twilight of February 9, 1971, a 6.6 magnitude earthquake struck Los Angeles. The shockwave rippled out over 300 miles, a stretch of land that ran from the California coast to Las Vegas. Highways split, bridges ruptured, and railroad tracks twisted out of shape. Some who experienced the disaster believed the United States of America, with Cold War relations lingering, had come under nuclear attack.

Gov. Ronald Reagan declared all 4,084 square miles of Los Angeles County — more land than Delaware and Rhode Island combined — a disaster area. When one of the Van Norman Dams, part of the Los Angeles Aqueduct that supplied the metropolis with water, threatened to collapse, tens of thousands of residents were ordered to evacuate. In all, 7 million area residents were on edge. Property damage to the city reached over $500 million, the equivalent of $3.8 billion in 2024.

As the dust settled, LA resembled the sprawling set of a disaster movie. Indeed, Hollywood used the day’s stark destruction to inspire the 1974 film “Earthquake,” which was later turned into a popular theme park ride. To some, the San Fernando earthquake felt tragic but inevitable: Los Angeles is, after all, an improbable city, a dream built into existence on semiarid land and an unstable tectonic plate. But the quake’s outsized devastation was fueled by poor regulation and weak infrastructure, the mistakes of men.

The earthquake caused indiscriminate damage to LA but wrought a disproportionate impact on those who had served in the military. At least 46 of the more than 60 people who perished that day were veterans. All were receiving care at the Veterans Affairs hospital in the city’s northernmost neighborhood, Sylmar. An entire wing of the clinic collapsed when the tremor hit. Lawmakers who later surveyed the razed facility compared its appearance to a “smashed-in orange crate.” Additional VA hospitals in the Valley, namely in Sepulveda — now called North Hills — and San Fernando, also suffered serious damage.

Before the disaster, none of California’s VA facilities had been built to withstand a major spike on the Richter scale. In its wake, Washington reexamined and strengthened its preparedness efforts, taking steps to, among other things, create the Office of Earthquake Hazard Reduction.

The VA and its overseers similarly promised action. They pledged to rebuild facilities and hired a team of seismic experts to assess the state of VA infrastructure across California comprehensively. “We have a lot of hospitals and a lot of veterans and staff who, in the wake of this tragedy, must be protected,” said then-U.S. Rep. Roman Pucinski, an Illinois Democrat on the House Veterans Affairs Committee. “Any way you look, it’s going to cost money.”

The results of the VA’s seismic analysis were withheld from the public. Instead, a year after the earthquake, the VA declared 30 of West LA campus’s 236 buildings uninhabitable. It then ordered the nearly 1,500 veterans who lived on the campus to vacate within a month. It was a grand eviction from land deeded to former service members, one that lacked any tangible plans to reinforce the infrastructure and rehouse the veterans of the future.

“[The VA] had no answers when we asked them for long-range plans to replace the hospitals,” vented Richard S. Skinner, an official with the nonprofit veterans service organization Veterans of Foreign Wars, in a news article published by the Press-Telegram after the VA’s decision.

According to the VA, the department sought funding from Congress to update buildings, and was provided enough to update medical facilities. “No additional funding was provided for all other repairs, such as residential buildings,” the VA says in a statement issued for this feature. Over time the only veterans living at West LA VA were those receiving medical care in an inpatient residential setting like the domiciliary, or DOM (known officially as a Mental Health Residential Rehabilitation Treatment Program), the department says.

The quake’s timing was terrible for vets. After World War II, when the veteran population quadrupled, the quality of VA medical care had shifted from worthy of commendation to worthy of criticism. Hospitals were overcrowded, medical staff was poorly qualified. Though the VA made progress in the years that followed — separating the medical staff from the U.S. Civil Service and establishing partnerships with local medical schools like the one with UCLA — by 1970, the VA’s still-inadequate medical care received renewed scrutiny in the pages of the Los Angeles Times.

The series of articles in the Times outlined stifled, long-simmering complaints by residents and staff about conditions at the West LA VA. Residents protested the lack of recreational facilities that had been put in place back in the early 1900s to discourage residents from leaving campus for saloons and gambling halls. They also raised concerns about improper use of profits from oil wells operating on the property, and a lack of security to protect them from the “strong-arm robberies” that happened regularly in a tunnel that allowed them to cross San Vicente Boulevard, a street that was once part of the property.

“They want us to make the passageway to their bars safe for them,” a spokesman for the VA told the Times. “We’re not in the business of encouraging our boys to drink. It is not our tunnel to police, maintain, or make safe.”

Medical patients and staff had more dire concerns. Underfunding had rotted the campus’s 1920s-era Wadsworth Hospital, where patients were “naked and bathed in feces because of lack of privacy and inadequate personnel,” doctors testified at the April 1970 Senate Veterans Affairs subcommittee hearing. They also complained of broken windows, poor ventilation, grime, and the continued use of condemned structures.

Following the hearing, Sen. Alan Cranston, the committee’s chair, sought $174 million in increased VA funding. His advocacy was met with resistance. One of Cranston’s biggest adversaries was President Richard Nixon, a fellow Californian Cranston fought on everything from Supreme Court nominees to nuclear proliferation.

In June, the West LA VA received just $300,000 from Washington to patch up Wadsworth Hospital. “What we need is a new hospital,” one of Wadsworth’s doctors said at the time, “but that takes at least seven years.” The slight was prophetic. The next year the earthquake hit, and six years after that, in 1977, the West Los Angeles Wadsworth VA Medical Center opened its doors. Also known as Building 500, the $83.7 million facility was the largest VA structure west of the Mississippi and featured nuclear medical and brain surgery equipment — but 300 fewer beds than the 1,133-bed Wadsworth Hospital shuttered by the quake.

The funds for this new hospital didn’t come easily. Even after the earthquake, in October 1972, Nixon vetoed a veterans healthcare package that would have secured vital structural improvements to the California campus. Outraged, Cranston railed against the president, saying the commander in chief was happy to spend billions in Vietnam but only “pennies to care for the men who fought his war.” He wasn’t wrong: Spending to support veterans rose significantly after World War II, but Nixon did not make comparable increases following the Vietnam conflict. Many months later, Cranston found that Nixon’s reelection campaign had improperly solicited political donations from VA officials. That evidence became part of the Watergate investigation.

While this political theater played out, veterans’ suffering deepened. On the same day the American Legion publicly sought assistance for veteran victims of the earthquake, the leader of the Jewish War Veterans of the United States declared that America’s “underprivileged and disenfranchised” Vietnam veterans were returning home without proper help. He warned that, absent massive government help, many returning service members would “explode,” a statement that proved prescient.

In the years since the U.S. pulled out of Vietnam, lawmakers have built new medical facilities on the West LA VA campus and allowed outside interests, public and private alike, to use its grounds for their own benefit. What they have not done is build new permanent veteran housing. Today a once-sprawling sanctuary dedicated to housing America’s military veterans has been chopped up and reallocated to seemingly everyone except those who have served. Generations of veterans have responded with anger, activism, and — sometimes — violence.

A Vet Counter-offensive

In his time navigating the VA, Shad Meshad has seen “hundreds of promises unkept.” A former mental health officer in the Army, he split his head open when his helicopter was shot down in Vietnam. Decades later, he hides the scars from this encounter under jet-black bangs. Meshad has often found himself in the sometimes violent middle between government bureaucracy and veteran advocacy. His tone is firm and sometimes impatient, informed by decades of stressful work.

After Meshad returned home from the war, he became a psychiatric social worker at the West LA VA. Like many vets, he found the campus to be an environment hostile to those it’s bound to serve. This was best exemplified by William K. Anderson, the West LA VA director under both President Jimmy Carter and Reagan and a stoic World War II vet who seemed skeptical of the rougher and scruffier Vietnam generation. Meshad says Anderson “didn’t have any opinion” on the issues plaguing his generation, and “that was the problem.” Among his unpopular decisions, Anderson shuttered a mental health ward in Building 258 that treated and housed veterans.

A senior bureaucrat, Anderson was largely confined to his office, disconnected from the VA’s patient population. Meshad, on the other hand, saw the devastating toll of Vietnam up close. He watched clients and battle buddies struggle with anger, depression, and anxiety. Some became violent and were incarcerated. Others died of addiction, Agent Orange-related ailments, or suicide.

Many were also homeless. This cohort included John Keaveney, who, after coming home from Vietnam, fell into a life of crime to support a heroin habit. He received mental health treatment at the West LA VA, where he vented about his intractable struggles to reintegrate into society. His counselor would listen, which he found helpful, but, “Then they’d tell me my session was over and I’d have to go live on the streets again and come back tomorrow,” Keaveney recalled during a 1996 interview with NBC Dateline. The agency ultimately failed to stabilize his life.

Fueled by the urgency of the city’s interconnected veteran crises, plus his own frustration with VA bureaucracy, Meshad helped pioneer a new model — the Vet Center — in which former service members could secure help outside the VA campus walls. At first, Meshad facilitated group therapy sessions in church basements, apartments, and legal aid centers. Veterans often complained about government inaction and their own invisible war wounds in equal measure. “Whatever you were feeling bad about, you had a chance to say it,” says Jesse Jay Morales, a Marine Corps vet who had completed three Vietnam tours.

Meshad’s grassroots approach was modest but effective. It was later systemized through $10 million carved out of the VA budget. It was barely enough to keep the lights on, but veterans nonetheless streamed through the door. Meshad became one of the few trusted figures among indigent veterans, a key conduit between the VA and the streets. In 1974, when a Vietnam veteran decked out in combat gear took three hostages in Griffith Park, Meshad was called upon to lower the temperature. In the end, he helped secure their safe release.

Many veterans who gathered at Vet Centers were galvanized into activism. One early fight concerned veteran burial. By the mid-1970s, many poor veterans were being laid to rest in nameless graves at civilian cemeteries. Meshad and others successfully pushed the city and the VA to ensure that all eligible veterans were given a proper military burial at Los Angeles National Cemetery, which abuts the West LA VA campus. Morales and others also managed to preserve a historic veteran outpost, Patriotic Hall, from being razed and redeveloped.

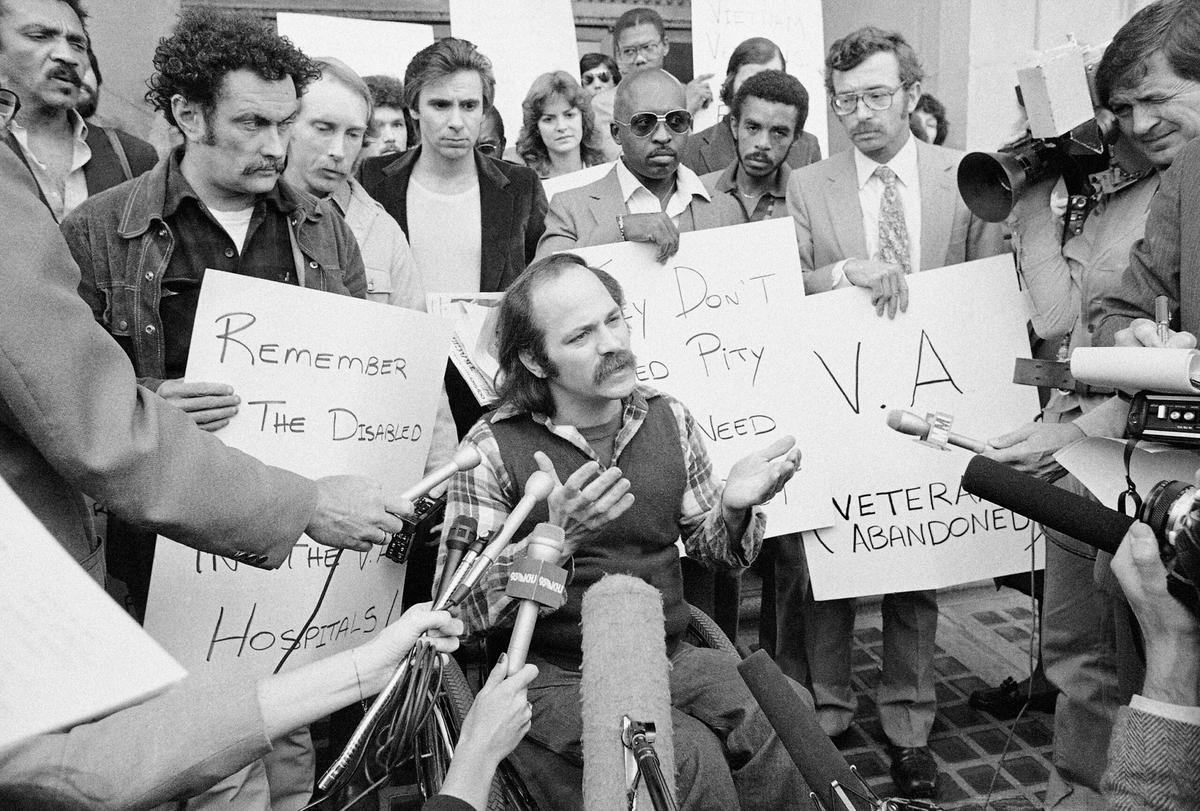

In 1972, Vietnam veteran Ron Kovic, author of the autobiography “Born on the Fourth of July,” interrupted Nixon’s Republican nomination speech to speak out in protest. In 1974, around a dozen disabled vets, including Kovic, staged a hunger strike in LA, the first of several such protests over the next decade. Incensed by an array of mistreatment, the vets demanded to meet with VA administrator Donald Johnson, who gave in after weeks of mishandling the issue and was dismissed months later, rather than face embarrassment at a Cranston-helmed Senate hearing.

These veterans also fought for the VA to better assist its most vulnerable patients, work that was marked by fitful progress. In 1977, for instance, the West LA VA launched New Directions, a popular program that provided temporary housing, treatment, and job training to veterans. Over the years that followed, however, the program was slowly starved of resources, then shuttered around the turn of the decade.

Reagan played the role of soldier numerous times during his Hollywood acting career. As president, he praised his real-world inspiration, once remarking that “veterans know better than anyone else the price of freedom.” His policies told a different story. As part of his broader plans to shrink government, he consistently underfunded the VA, exacerbating staffing issues and wait times. At one point, he attempted to ax the Vet Centers, though the model’s success made it politically impossible to kill. There are more than 300 Vet Centers across the country today.

The agency’s uneven and oscillating policies engendered deep frustration among vets in Los Angeles and beyond. An extraordinary example was James Hopkins, who, in early 1981, drove his jeep through the West LA hospital’s plate glass doors and started shooting. Miraculously, no one was seriously injured. Hopkins was apparently angry that the VA wasn’t assisting him with his hearing issues. A month after his attack, he died alone of an apparent drug and alcohol overdose.

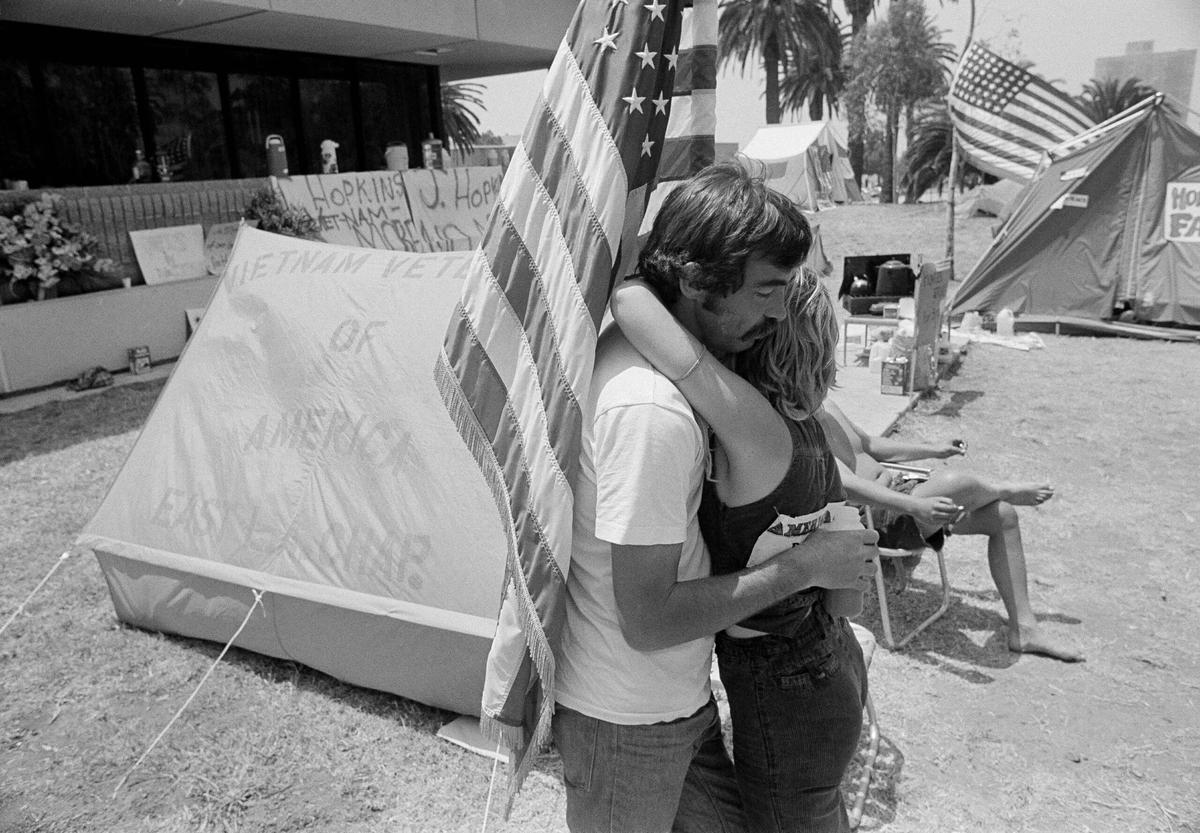

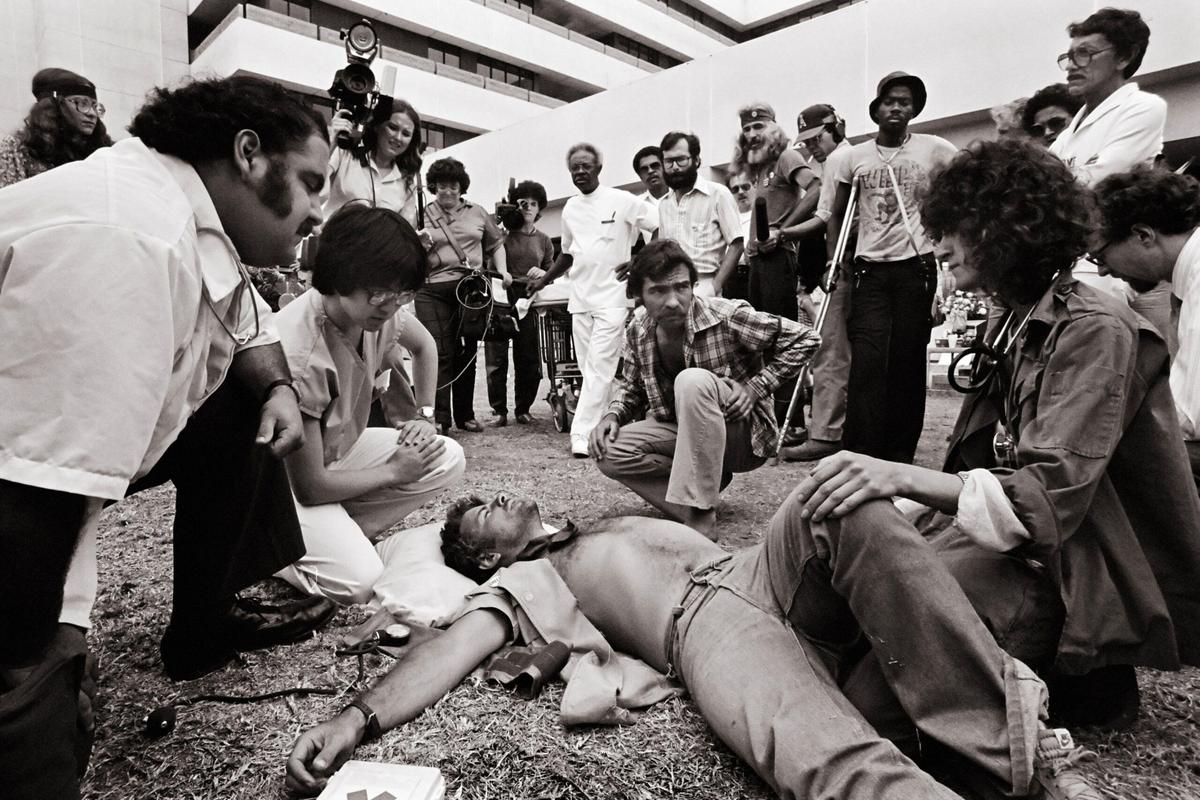

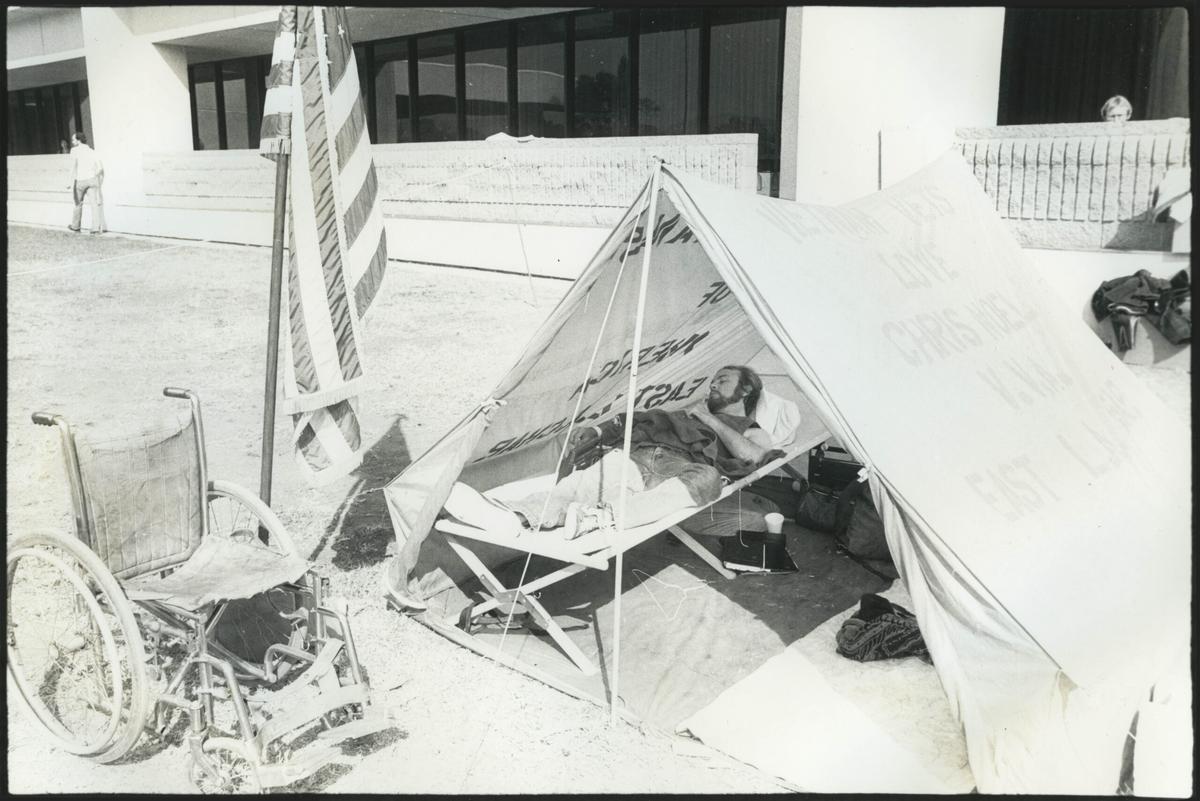

On a warm May morning, three days after Hopkins’ death, Keaveney, Morales, Kovic, and other combat vets erected a tent city on the hospital’s sprawling lawn and launched another hunger strike. Each had his own issues with the VA. Some were homeless and wanted beds. Others suffered from welts, blisters, and other puzzling ailments they suspected were the result of Agent Orange exposure. The striking vets demanded the VA provide them with better treatment and more support. They also called for an investigation into how the VA failed Hopkins. For weeks, they refused to leave the campus lawn, ingesting fruit juice and vitamin pills.

The vets’ activism elicited national news coverage that highlighted the terrible impacts of conflict, and also the government’s failure to heal war wounds. “We want vets to stop being killed by the Veterans Administration,” said Virgil Neigel, a 30-year-old vet with long hair and a thick mustache, to a local paper during the strike. Various Hollywood luminaries visited the veterans, including Jon Voight, who’d recently earned an Oscar for his portrayal of a vet with a disability in the film “Coming Home.”

Rather than listen to the concerns of the strikers, the VA took a war footing. Administrators militarized the West LA campus and called security on frustrated vets seeking care. Meshad, who served as the de facto middleman between the government and the vets, recalls hospital police, the LAPD, SWAT teams, and FBI agents on the campus during the hunger strike. “They had snipers on the roof or whatever.”

It was on the lawn that Morales first realized the incredible potential of the surrounding campus. “They had completely empty buildings where they had housed and helped World War II and Korean War vets,” he says. There were signs of former splendor on the campus, and, in Morales’ words, the VA had “let it go to hell.” The Japanese garden had wilted. Sewage and medical waste leaked across the lawn.

A few weeks into the protest, Sen. Cranston visited the strikers and listened to their concerns. He arranged for some to speak in Washington. Despite pleas from Kovic and others, President Reagan refused to meet with the protesting veterans. Inside the White House, staff called the vets’ demands “absurd.” The first request on the veterans’ list was “a Housing Program be implimented [sic] for Vietnam Veterans that is comenserate [sic] with that given to veterans of World War II.”

The strike ended after seven weeks, in July 1981, after the White House — which, that March, had floated at least $700 million in VA cuts — pledged more support to the VA, including action on Agent Orange. The administration noted that the University of California had just secured a $114,000 contract to study the effects of the herbicide.

Meshad, who had helped broker the deal, says he hoped Reagan would deliver. But the president’s promises were little more than political posturing. Not long after the strike ended, Reagan pushed to end free VA care for veterans older than 65. And though the vets’ pressure campaign compelled Reagan to sign the Veterans’ Health Care Act of 1984 — which provided guidelines for VA police officers, allowed for the designation of post-traumatic stress disorder programs, and more — it also included a rider that expanded the terms of the 1948 law that allowed UCLA to build a medical school on VA land. “I am concerned that this provision ignores both the justification for the original transfer in 1948 and the taxpayers’ interest,” noted Reagan upon signing the 1984 law. “That federal real property is an asset that deserves management in the interest of the taxpayer.”

It wasn’t long before his administration had a change of heart about what was “in the interest of the taxpayer.” In 1986, Reagan’s VA leadership deemed more than 100 acres of the West LA campus as “excess” to the needs of veterans, potentially positioning it to be sold off to offset a federal deficit. Congress defeated the effort.

Some former strikers were pushed to the breaking point. In September 1981, a 35-year-old veteran named Clarence Stickler jumped from the 11th floor of the Los Angeles Hilton and died. Keaveney, for his part, felt deeply cheated by the government and saw Meshad as complicit in the VA’s broken promises. Once the deal fell apart, he made threatening phone calls to Meshad. Then, in 1982, he took Meshad hostage at his VA office, where Keaveney held a 12-inch knife to the man’s throat. Keaveney was dizzyingly high and drunk. After six hours of holding Meshad hostage, he passed out, giving Meshad a brief opportunity to flee. But Keaveney quickly regained consciousness, and, still desperate to punish Meshad, stole the captain’s bars from Meshad’s jacket, which hung on the office door, and replaced them with a private’s stripe. Keaveney viewed that theft as a down-and-dirty demotion. Then he fled to the streets.

Keaveney was eventually arrested, though Meshad declined to pursue charges. Meshad was angry, yet aware that the war had damaged Keaveney, as it had many of his clients. Meshad’s compassion allowed Keaveney to secure a spot at New Directions where he was provided housing and job training. There, Keaveney got clean and wrote an emotional apology to Meshad.

Keaveney later became a VA janitor, cleaning up the campus where he’d once almost killed a man. “The change in him is a miracle,” Meshad told a reporter in 1992. “He’s on a mission like nobody I’ve seen in a long time.”

Friendly Fire

New Directions provided Keaveney the space and support to find a new path in life, but the treatment and housing program shuttered completely in the late 1980s, foreclosing future opportunities for other veterans in need.

The end of New Directions came as major changes in federal economic policy took hold under President Reagan. Budget cuts and reallocations targeting the poor and near poor led to widening income inequality and increasing poverty. Veterans were not spared: Reagan’s 1987 budget slashed spending on vets’ health care benefits even as he signed the Department of Veterans Affairs Act into law, elevating the VA from being the government’s largest independent agency to the 14th Cabinet-level department in the federal government — still just as big but theoretically more influential in the White House.

Meanwhile, veteran homelessness spiked across the nation. By 1987, as many as 700,000 homeless people had once worn a uniform. That year, the West LA VA opened a housing program called the Comprehensive Homeless Center in Building 212, which remains in operation today. Around this time, U.S. Circuit Court Judge Harry Pregerson, a World War II veteran who’d been badly injured during the Battle of Okinawa, helped establish the Salvation Army’s Haven Program, located on the West LA VA campus, which provided additional housing and support services for homeless veterans.

Ambitious ideas were floated to address veteran homelessness, many of which focused on reviving the West LA campus, but few left the drawing board. In 1987, the House Veterans Affairs Committee failed to secure $15 million to turn unused buildings at VA hospitals across the country into rehabilitation centers. That same year, Cranston also unsuccessfully pushed to pass legislation mandating that the VA convert homes it had foreclosed on through its loan programs into shelters.

In its capacity as the federal government’s budget authority, Congress didn’t just fail to solve the problem, it exacerbated it. In the late 1980s, legislators slashed the number of VA benefits counselors — officials meant to connect vets with jobs, healthcare, and housing. As a result, less than 5% of Los Angeles-area veterans were receiving their earned benefits, a stark gap that illustrated profound failures by VA leadership to serve its constituents.

Efforts to mitigate dwindling veteran support faced fierce opposition at the local level. The suburban Brentwood neighborhood surrounding the VA campus had become especially affluent. Some homeowners were made uncomfortable by the presence of struggling former service members and eager to revive the century-old campus for their own interests. In 1988, Judge Pregerson floated a new plan to house homeless veterans and their families in 15 modest trailers on the West LA campus, but he abandoned the initiative in the face of community criticism. “We know there is a homeless problem out there, but the Veterans Administration property is not the place to solve it,” Sue Young, the president of the Brentwood Neighborhood Association, told the Los Angeles Times.

Few of Brentwood’s elite expressed outward disdain for veterans. Instead, some masked their opposition under the guise of veteran advocacy. A prominent example of this strategy was a nonprofit called the Veterans Memorial Gardens Foundation, which was chartered in the late 1980s and later became known as the Veterans Park Conservancy. Both organizations were led by Sue Young, who could not be reached for comment. Shortly after she established the foundation, Young secured free office space from the VA in the Eisenhower Office Building, which the organization described in its own documents as offering perks such as “abundant free parking” and “close proximity to the project sites and the easy access to VA administrators.” The conservancy’s foundational documents outline plans to raise millions from local community interests to support programs including tree plantings and outdoor concerts. A proposed job description for the executive director included overseeing projects “after they are completed per agreement with the VA” and maintaining a “positive and close relationship with VA.” The nonprofit took an intense interest in how the West LA campus would be used.

When the VA undertook a land utilization study in 1986, its stakeholders included Young and officials from UCLA, which had raised the prospect of adding a women’s softball field, a storage center, and research buildings. The resulting report, published in 1989, lists and blesses many “joint ventures” that had popped up on the campus, including oil leases, UCLA’s baseball stadium, and parking for a retail center called Brentwood Village.

Anderson, the West LA VA director at the time, appeared open to further development. In 1990, the Brentwood School proposed plans to construct six tennis courts, which it billed as jointly benefiting veterans and citizens alike. In a letter to the VA’s regional director, Anderson requested approval for courts, writing, “We appreciate your continued support for the planned development and use of this valuable VA land.” A representative for the Brentwood School notes that the school has partnered with the VA dating back to 1972, adding the relationship “has always been a mutually beneficial collaboration.”

When veterans raised concerns over these developments, forces across the city showed little interest in joining their cause. “We veterans were essentially powerless,” says Dave Culmer, a Vietnam veteran and long-time activist. He recalls raising VA land issues to Zev Yaroslavsky, the powerful supervisor of Los Angeles County. “He promised to pick up the issue in three months,” Culmer recalls. “That never came.” It seemed, at times, that Brentwood’s allies were everywhere. As Culmer ramped up his advocacy, he says that “various attorneys came to me and wanted me to relax my grip on this issue.”

Frustrated by these failures, the Vietnam Veterans of America, with the National Coalition for the Homeless, sued the VA to implement a nationwide housing program. “Nothing happened,” says Meshad. In 1991, California’s Republican governor Pete Wilson vetoed a bill that would allow California voters to check a box on their tax returns to designate money for homeless vets. The same day, he signed a law to build a veterans’ memorial. “Little is being done because the public has this perception that the VA is taking care of veterans,” Michael Blecker, a long-time veteran advocate, told the San Francisco Examiner that year. “It isn’t.”

In 1992, perhaps anticipating broad spending cuts under President-elect Bill Clinton to address a yawning national deficit, President George H.W. Bush — a Navy pilot in World War II and Reagan’s vice president — signed into law the Homeless Veterans Comprehensive Service Programs Act. The bill funded new pilot programs for homeless veterans and granted the VA the authority to lease, for a term in excess of three years, “any real property at the West Los Angeles Veterans Affairs Medical Center” solely “for the provision of services to homeless veterans and the families of such veterans.”

That same year, Keaveney revived New Directions, the program that saved his life. This time it would be funded with a mix of private and public money. Keaveney signed a 50-year lease and stood up the program in a West LA VA building that had been vacant for 20 years.

Yet that same year, developers proposed building a football stadium on VA grounds for potential use by the NFL and UCLA. The Veterans Park Conservancy rallied against it, instead pushing for a 45-acre memorial park for quiet reflection. This was a revision of its previous proposal for tennis courts, a rose garden, and a jogging track, according to a special report in the Los Angeles Times. The report noted that the Conservancy raised hundreds of thousands of dollars from affluent neighbors who received letters exhorting them to “save our community from illegal commercial development [and] preserve the last open space in” West Los Angeles. Escalating the private-interest turf war, the Conservancy claimed that the stadium’s boosters — “nonelected bureaucrats,” Young told conservancy supporters — circumvented normal VA channels and reportedly went directly to the White House with their plans. A Clinton administration official denied the charge.

By 1995, the stadium proposal was dead. UCLA said it was no longer interested in such a facility and both Los Angeles NFL teams, the Rams and the Raiders, decamped to new cities. The memorial park proposal was a different story. After a bill that would have facilitated its creation died in session, Sen. Barbara Boxer, a Democrat, reintroduced it in 1997. Outraged veterans wrote letters and made calls to her office. Boxer’s own personal landscaper, a Vietnam vet and president of the Vietnam Veterans of America California State Council, went to the senator’s house and “told her there’s something stinky about this whole thing,” he recalled to the Los Angeles Times in 1998.

The following year, the master plan for the West LA VA listed a 20-year agreement, starting in 2007 and with an optional 10-year extension, with the Veterans Park Conservancy for a 16-acre memorial park and “healing garden.”

A New Generation Rises

In 2000, the issue of veteran homelessness was supercharged in the public consciousness by an unlikely advocate: Miss America. Moments after winning the title, Heather French, draped in an ocean blue dress and wearing a sparkling crown, appeared before dozens of reporters and flashing cameras. At a lectern, she laid out her desire to travel the country and push forward common-sense veteran housing policies: “It’s not the prettiest platform, ladies and gentlemen, but it’s one that I believe is necessary.”

Over the next year, French traveled more than 300,000 miles across the United States on a national speaking tour titled “Our Forgotten Heroes: Honoring Our Nation’s Homeless Veterans.” A Kentucky native, she had grown up accompanying her father, a disabled Vietnam veteran, to appointments at the Cincinnati VA. “Issues that face veterans face the whole family,” she said. French spotlighted the country’s 250,000 homeless veterans and demanded the government do better. “She has done a great job for the veterans,” said Pete Gnirk, a Wisconsin veteran, to an Associated Press reporter during the Midwest leg of her journey. “She has done more for us than the Congress has.”

In Washington, French advocated for an ambitious bill, named in her honor, that would extend more VA services to homeless veterans and ramp up resources to get them housed. The urgency of this issue was illustrated in June 2001, when a homeless Army vet named James Clark was beaten to death as he slept at an encampment on the edge of Ventura, California, 60 miles up the coast from the West LA VA. He was 58.

In December 2001, President George W. Bush signed a version of French’s bill into law that allocated more than $1 billion for the issue, including through the creation of a joint HUD-VA housing voucher program.

Two years later, in 2003, the House tried to slash nearly $15 billion worth of veterans’ programs. At risk, according to an opinion column for The Boston Globe, was “money for disabilities caused by war wounds, rehabilitation and health care, pensions for low-income veterans, education, and housing benefits, and even — nice touch — burial benefits.” Even President Bush’s VA Secretary, Anthony Principi, publicly complained that the president was not adequately funding the agency. “I asked [the Office of Management and Budget] for $1.2 billion more than I received,” he told a House committee.

In 2009, President Obama’s first VA Secretary, Eric Shinseki, penned an op-ed heralding a five-year initiative to solve homelessness. Not long after, he announced funding for a plan, introduced three years earlier, to convert three West LA VA buildings — 205, 208, and 209 — into housing.

It was a good time for unhoused vets to be optimistic: In 2010, then-Calif. Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger broke ground on a $253 million, 396-bed housing facility on the same campus to be run by the state’s Department of Veteran Affairs. But the good vibes would be short-lived. Plagued by design defects and bureaucratic boondoggles, the state facility had filled only half its beds four years after its construction, and Shinseki’s effort was similarly dysfunctional. It wasn’t until 2017, nearly a decade after his pledge to end veteran homelessness, that the first building – 209 – went live. Three more opened in 2023.

The Vietnam generation was frustrated but unsurprised by these deflated promises. Many veterans were irked by other shiny and mostly unhelpful initiatives, like when the VA spent 18 months and $1.1 million renovating the Historic Women Veterans Rose Garden — the “healing garden” in the Veterans Park Conservancy’s memorial park plan. At the grand reopening, Robert Rosebrock, an outspoken veteran activist, said the money and resources would be better spent on providing a roof for vets to sleep under, according to the Los Angeles Times article covering the event.

Vietnam-era activists continued to fight, but many were getting old and sick. Morales, the hunger-striking, three-tour Marine, had cancer and serious respiratory problems. But he was motivated to help the post-9/11 veterans. His son had served in Iraq and returned as a different person, mentally troubled and struggling with alcohol. “He was a good, clean all-American kid,” Morales says. “He’s been a wreck for the last 20 years.”

In the early aughts, many Vietnam-era stalwarts passed their research and knowledge to a new crew of post-9/11 advocates, a group Morales continues to occasionally advise. “I’m their guru,” he half-joked. One of the first people he connected to from this generation was Michael Dowling, a fellow Marine vet he met at a veteran hiring event in front of the city’s federal courthouse. Dowling and a dozen or so other younger vets began to organize in the mold of the Vietnam generation. Laser focused on housing veterans, they weren’t afraid to use their predecessors’ most effective tool: encampments.

The group soon found an ally in Bobby Shriver: nephew of John F. Kennedy, brother of Maria Shriver (who was married to Schwarzenegger for more than three decades), and, at the time, mayor of nearby Santa Monica. Shriver, who today runs a veterans’ nonprofit, first became involved in LA politics around 2004. That’s when a spat with the city over the height of his hedges pushed him to run for the Santa Monica city council. He won. Once in office, Shriver turned to more substantive issues, including the growing homeless population. After a friend mentioned that there were massive unused facilities on the 388-acre campus of the West LA VA — just a mile down the road from Santa Monica’s city boundary — Shriver set up a formal visit with an eye toward turning the buildings back into apartments.

“They hadn’t been well maintained, there was a bunch of dirt, asbestos, and other bullshit,” Shriver recalled in a 2021 interview. “I thought, ‘I will be able to fix this up pretty quickly.’ Of course, I was wrong.”

Like many before him, Shriver strived to remake the West LA VA campus into a place that supported veterans, a goal that again ruffled feathers among California’s political and Hollywood class. Shriver remembered one memorable exchange with former U.S. Sen. Dianne Feinstein, a Democrat who is now deceased, in which she asked, “Are you sure people will want to live there?”

“Senator, it’s in Brentwood,” Shriver replied. “If you make it look like Brentwood, people will want to live there.”

The post-9/11 advocates were allowed to organize in the offices of Shriver’s sister, Maria Shriver, who had a roomy spot just across the street from the West LA VA hospital. “We were planning out how to rebuild a campus that we could see out the window,” Dowling says. The work was people-powered and received little support from traditional Veterans Service Organizations (VSOs), such as the American Legion, the VFW, or Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America (IAVA). Some groups saw the fight as too risky, others wanted to join in only to secure political power.

Some VSOs seemed more interested in name recognition than helping, Dowling recalls. “It felt like there was manipulation, kind of, you know, backdoor dealings that were going on instead of all of us coming together.”

By this point, new developments had sprung up on the West LA VA campus with little or no connection to the veteran mission. There was a dog park and a laundry facility for Marriott Hotels, as well as the sprawling athletic facilities for students of UCLA and the Brentwood School. Oil drilling and natural gas processing continued unabated. And 20th Century Fox used some space to store sets. Meanwhile, a new generation of nonprofits established to support the military carried ties to UCLA and Brentwood, stoking skepticism and concern among the veterans.

In 2011, Shriver spearheaded a lawsuit with the ACLU to sue Shinseki, alleging discrimination against disabled veterans and misuse of the West LA campus. The case’s lead plaintiff was Greg Valentini, a Lakewood, California, native who had spent time on the streets after returning from grueling combat tours in Iraq and Afghanistan. Valentini was a bit uncomfortable with the media attention the suit brought. “I don’t want to be a whiny vet,” he told the Los Angeles Times in 2011. He was also clearly troubled by his terrible war experiences, which the suit dredged up. In their legal complaint, lawyers chronicled how the Army veteran survived sniper fire overseas and watched fellow soldiers, as well as innocent children, die.

After returning home, Valentini couldn’t keep a job and struggled with drug abuse. At one point, he lived in a tent by Long Beach Airport, close to his hometown and 30 miles southeast of the West LA VA campus, bathing in a nearby lake and getting his meals from garbage cans. Valentini briefly secured housing from U.S.VETS, a nonprofit run by Steve Peck, a Vietnam veteran and the son of Oscar-winning actor Gregory Peck. Valentini also landed in a temporary housing program on the West LA campus, but had difficulty resisting easily accessible drugs. He said one of his roommates died of a heroin overdose.

The land misuse lawsuit came to an end in 2013. In a promising decision, U.S. District Judge S. James Otero sided with Valentini. Otero struck down the outside leases, saying they were “totally divorced from the provision of healthcare.” He also halted construction of an amphitheater on the property and ruled that the land was statutorily required to serve veterans. The decision paved the way for the campus to finally be rehabilitated to its former greatness.

Then, in a shocking turn of events, the Obama administration appealed the decision. That position crumbled, however, after summer 2014, when Shinseki resigned over an unrelated wait-time scandal at a VA hospital in Phoenix. He was replaced by Bob McDonald, a West Point graduate and the former CEO of Procter & Gamble.

Once settled into his wood-paneled office overlooking the White House, McDonald ordered an analysis of veteran homelessness. He quickly realized LA was the epicenter. According to McDonald, he told his staff, “If you don’t solve homelessness in Los Angeles, you don’t solve homelessness nationally.” McDonald says the general counsel refused to settle the suit and told him not to visit the West LA VA campus because of the pending lawsuit.

McDonald fired his counsel and began visiting LA every month or so to speak with veterans’ advocates, including Shriver. “When training in the military, you’re taught to run towards the sound of gunfire,” McDonald says. “A lawsuit certainly sounds like gunfire.”

Once he had the lay of LA’s land, McDonald replaced the local director, the chief of staff, and the chief medical officer. He then settled the court case and agreed to an expansive new master plan that promised to refurbish the VA campus, build nearly 3,000 housing units, and lease land only to organizations that help veterans — part of a national pledge to stem the homelessness crisis.

McDonald stood with Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti in January 2015 when Garcetti reiterated a promise to end veteran homelessness in the city by the end of the year. Two missed deadlines and two years later, the two leaders reconvened to discuss the more than 1,200 veterans still living on LA streets. “Every time we set a goal,” Garcetti offered to the Los Angeles Times, “we’re getting closer.”

Renewed Promises

There was reason to believe McDonald’s optimism would be unlike so many broken promises before it. With the arrival of the Obama administration came a broad push to house veterans, part of a 2008 campaign trail promise. With Democratic majorities in both houses, Congress provided funds for 10,000 additional vouchers each year from 2008 to 2010 — when automatic spending cuts known as sequestration eliminated 100,000 vouchers in 2013, a divided Congress moved to restore them over the next three years.

The White House, meanwhile, threw a spotlight on the issue. It challenged city and county officials to reduce veteran homelessness, facilitated coordination between levels of government to make change in the area, directed the VA to expand the capacity of its veteran crisis hotline by 50%, and launched a predictive data program to identify and intervene with those at risk of losing their homes.

By the time the Valentini v. Shinseki legal settlement was finalized in January 2015, more than 40,000 post-9/11 veterans had fallen into homelessness nationwide. Politicians seemed newly invigorated to tackle the issue. That August, U.S. Sens. Feinstein and Boxer introduced a bill to curtail illegal land leases and swiftly house veterans. The threat of this legislation alone pushed some leasing interests to embrace the veteran population. One was the Shakespeare Center, which eventually enlisted dozens of vets to work backstage at shows it staged in the VA’s Japanese Garden. As part of a broader charm offensive, Brentwood businesses began rebranding their parking lots as “veterans’ parking lots.”

President Obama’s broader veteran housing campaign proved successful. By the time Donald Trump came into office, the VA had essentially halved the country’s veteran homeless population. Roughly 80 or so municipalities had met the government’s definition of eradicating veteran homelessness entirely, as had a few states, such as Connecticut and Virginia. While the LA project was meant to be a crown jewel in this effort, work had repeatedly faltered.

Once again, another administration — bringing the total to eight presidents, including six who were veterans themselves — had failed to correct the missteps in LA since the earthquake hit four and a half decades earlier. Deadlines weren’t met, promises weren’t kept, and a new generation of veterans found themselves living and dying on LA streets. Among them was Valentini, who struggled to stay sober and, a few years ago, slid back into a transient life.

Meanwhile, the VA moved slowly on finalizing its master plan, missing major deadlines and falling years behind on its post-suit promise to build 1,200 units. They also allowed further development on the grounds, including a baseball practice field for UCLA. The VA also made unrelated moves that further frustrated patients. In 2018, for instance, the VA shuttered its group therapy PTSD program, which had helped homeless vets stabilize their lives and secure housing.

In April 2022, the VA released another new master plan. It was comprehensive but years behind schedule. A new VA secretary, Denis McDonough, rehashed the promises of his predecessors and acknowledged the string of prior mistakes.

“Talk is cheap,” Keith Harris, McDonough’s point man on homelessness, told reporters at the time. “Watch our actions.” Harris cited plans to create 180 new units by the end of 2022. “If we can bring those about this year on time, I think that’ll be an important step in rebuilding credibility,” he said.

The VA later failed to meet this deadline, opening just 54 units by year’s end. By June of the following year, however, 233 units had opened and today they are more than 95% occupied.

GET UPDATES FROM THE FRONT

Follow the veterans’ fight for housing at the West LA VA and receive court briefings from the trial.