The Rise and Fall of the Soldiers Home

In 1888, hundreds of acres of undeveloped Los Angeles real estate were donated to the U.S. government to house disabled soldiers. This visual history tells what happened to that land and why vets stopped living on it.

The story of the West Los Angeles Veterans Affairs campus begins in March 1865. One month before Abraham Lincoln’s assassination and the Confederate army’s surrender in the American Civil War, the president signed legislation establishing the National Asylum (later Home) for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers — a predecessor of today’s VA. Amid the staggering rise of injured veterans, one facility became many and formed an eventual network of at least a dozen soldiers homes nationwide that provided housing and services for those disabled by military conflict.

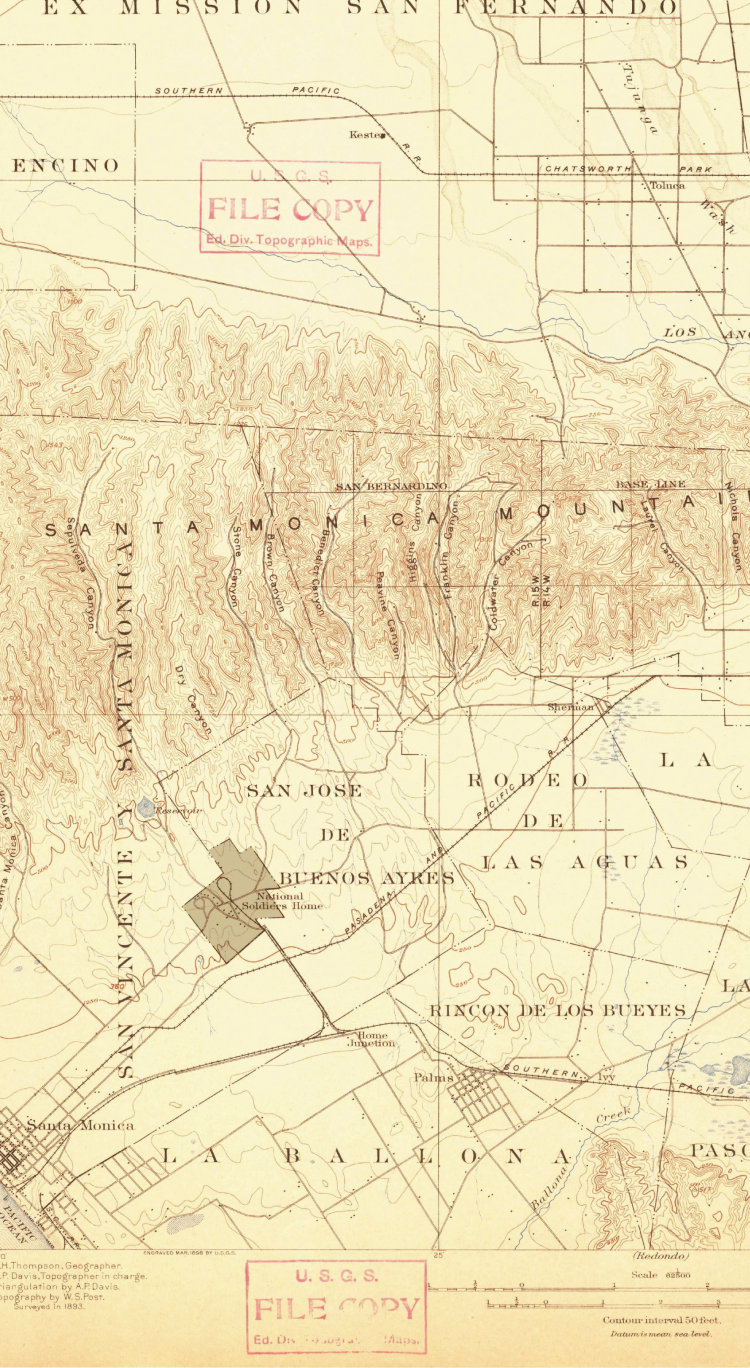

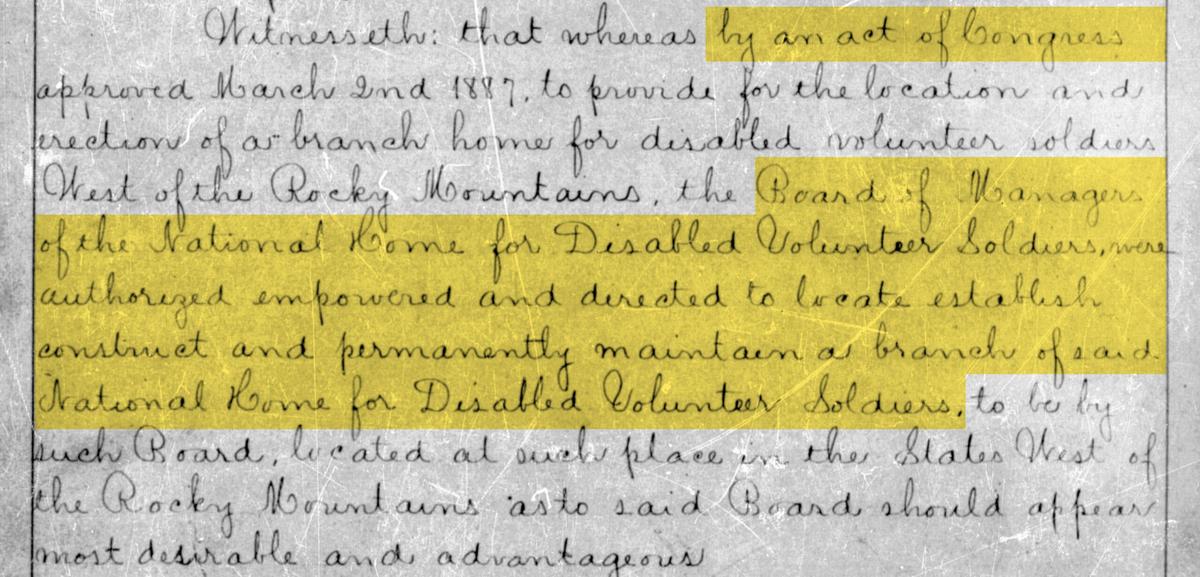

By 1887, with congressional approval “to provide for the location and erection of a Branch Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers west of the Rocky Mountains,” that network reached the West Coast. The burgeoning metropolis of Los Angeles, amid a population boom driven by the area’s mild climate, was chosen as the ideal location for the Pacific Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers.

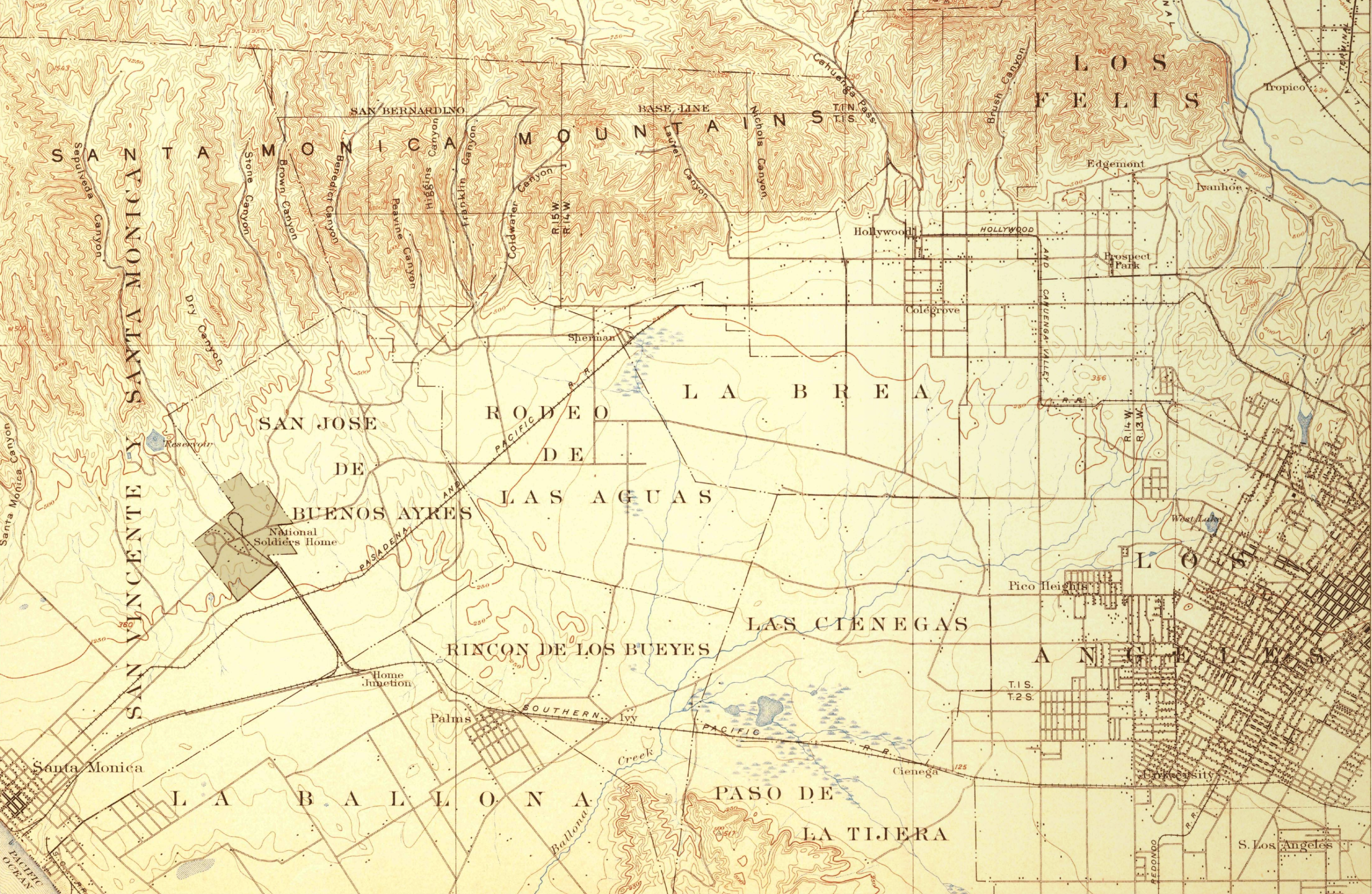

Competition for the facility — and the federal spending that came with it — was fierce. The National Home’s Board of Managers considered more than 70 sites in California before accepting an offer to place it at the foothills of the Santa Monica Mountains, about 5 miles from the Pacific Ocean, in an area that would first be called Barrett Villa, then Sawtelle, then West Los Angeles.

The winning bid came from a powerful trio that had incorporated the nearby City of Santa Monica only a couple of years prior: industrialists Sen. John Percival Jones and Col. Robert Symington Baker, along with Baker’s wealthy landholding wife, Arcadia Bandini Stearns de Baker.

The group offered the federal government 300 acres of free land, 150,000 gallons of water a day, and $100,000 for property improvements (equivalent to more than $3 million today). In 1888, the Los Angeles Times praised the location, writing, “It will cause land in that section to advance in value, and the trade thrown into the way of our merchants will be considerable.”

The borders of the Soldiers Home property have ebbed and flowed greatly in the years since its establishment. Additional donations of land by the Santa Monica Land and Water Company (formed by Jones and Baker), John Wolfskill, and Roy Jones (son of the senator) added at least 330 more acres to the property. In 1890, the National Home’s annual report listed the Pacific Branch’s area at 570 acres. Government records in 1900 said it was 631 acres. By its 1919 annual report, the property had swelled to more than 722 acres, making it the largest veterans’ campus in the country and almost one and a half times the size of today’s Disneyland Resort. As of 2024, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, which now oversees the land, lists the West LA VA campus at 388 acres.

Veterans in need awaited the Pacific Branch with great interest, even though its opening came two decades after the Civil War’s end. The first resident, Pvt. George Davis of New York, did not even wait for the completion of the construction of the first barracks; he camped out on the campus grounds in 1888. By February of the following year, around 50 disabled veterans had made their home on the property.

Two years later, the campus had more than 600 occupants. There were four two-story barracks, hot water, and about 40,000 ornamental trees that provided shade. Vets could visit a commissary, blacksmith, shoemaker, and tailor — and a beer hall that poured free suds on July 4. “The arrests at the Home and in the town have been very few,” wrote the branch’s governor in his annual report. “The only dissatisfaction has been on the part of the proprietor of the ‘Blazing Stump,’ a disreputable saloon near the Home.” The campus also had a hospital that included influenza patients during the pandemic from 1889 to 1890. As of the report date, 47 people had died there.

By the turn of the century, a couple thousand pensioners were using the property, which by then had become a working farm, producing 640,000 pounds of vegetables and 100 tons of hay annually — all harvested by veterans.

A HAVEN FOR HEROES

On May 9, 1901, more than 12 years after the Pacific Branch opened, thousands gathered to hear President William McKinley, a Union Army veteran, formally dedicate the Pacific Branch of the National Soldiers Home. “The government for which you fought, to which you gave the best years of your lives — that government will see to it that in your declining years you shall not suffer,” he said, “but shall be surrounded with all the comforts and all the blessings which a grateful nation can provide.”

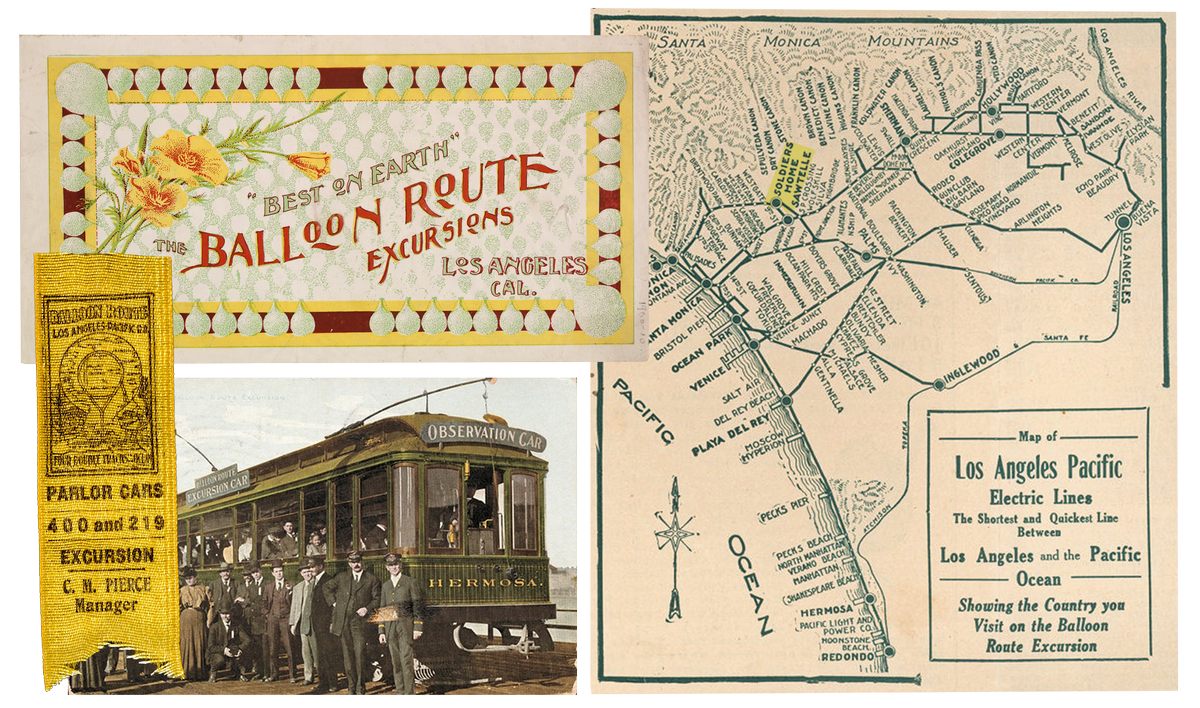

By 1904, the Pacific Branch had established its place on the LA map, becoming a stop on the Pacific Electric Railway’s “Balloon Route,” an elliptic sightseeing train line designed to entice residents of downtown Los Angeles to explore coastal areas where real estate was still for sale. One brochure described the National Soldiers Home as “a park covering 700 acres — aptly termed the ‘Old People’s Paradise.’”

Some 2,300 veterans lived there by mid-1910, and they enjoyed the benefits of a small town. The landscaped campus included two recreation halls, a library, billiard and pool tables, and a 20-piece brass band that played daily concerts. Retired soldiers kept to strict military protocol, slept in close quarters in the barracks, ate communally, and were made to wear dark blue uniforms. Veterans also needed permission to leave the campus for longer stretches of time and answered to codes of military discipline.

1.

1.1. The Barracks

There were four two-story barracks to start. Each was 207 feet long and 26 feet wide, and featured a 12-foot-wide piazza along the front and around each end. The center-gabled structures were warmed with steam and lighted with oil lamps, and they had one fireplace. The residents’ lockers were made of redwood but resembled mahogany.

2.

2.2. The Chapel

The interior of the Wadsworth Chapel, built in 1900 and still standing as the oldest structure on campus, was separated by a “heavy brick wall,” according to a 1907 brochure of the campus, allowing for both Catholic and Protestant services.

3.

3.3. The Dining Hall

The Pacific Branch’s dining hall served three meals daily: breakfast, which often consisted of heartier proteins like beef stew, potatoes, onions, bread, butter, and coffee; dinner, which doubled-down with dishes like boiled beef, gravy, pink beans, potatoes, bread, and tea; and supper, which included cold meat, bread, butter, and tea. Seasonal fruit, including melons, also found its way onto veterans’ plates.

4.

4.4. The Memorial Hall

Completed in 1898, Memorial Hall had a stage and assembly room for plays and concerts for veterans. Amusements and recreations like these were provided to discourage residents from leaving the Soldiers’ Home for off-campus saloons, gambling halls, and other vice dens.

Though idyllic in many ways, the Pacific Branch was not immune to challenges. Returning soldiers sometimes carried illnesses that included yellow fever, tuberculosis, and smallpox. Some veterans were robbed in their sleep, beaten by the Home’s police force, or left for dead when they couldn’t work the fields, according to newspaper reports from the time. And though the strict military protocol was familiar, it wasn’t always preferable. In 1911, muckraking journalist John S. McGroarty found the conduct in the mess halls and barracks was “such as to degrade the men, not to speak of the sufferings it imposes on them.” Documents from a Senate hearing the following year described the Pacific Branch as “a vast detention barracks, under an unnecessarily rigid system of discipline,” and led the inspector general of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers to assume control of the campus for a stretch.

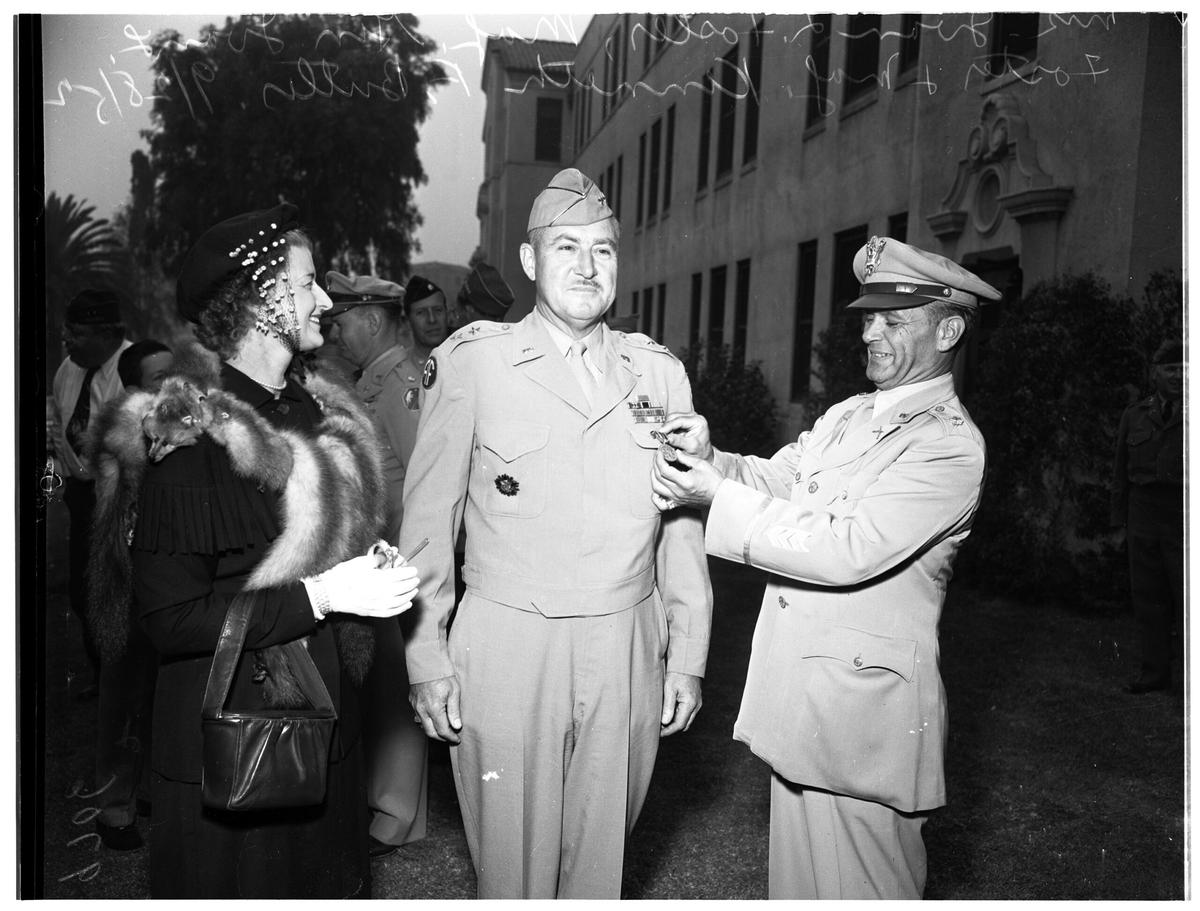

MILITARY INFIRMARY COMPLEX

It wasn’t long before the old people’s paradise became a young man’s purgatory. After the United States entered World War I in 1917, the need for health services and living space for veterans surged. The conflict’s trench warfare and new weaponry meant more than 204,000 of nearly 5 million veterans returned home with novel disabilities, often to their faces and upper bodies.

The Pacific Branch modernized its campus to expand medical capacity and established specialized facilities, such as those for neuropsychiatric use, to help treat “shell shock” — what we now call post-traumatic stress, or PTS.

Though the Pacific Branch served only male veterans, women made up the majority of the facility’s 162 nonmember employees in 1919, some working as nurses. In 1925, a Soldiers Widows Home was constructed on three acres using donated funds — a notable example of civilian housing on land meant to exclusively house veterans. Today a National Guard recruitment office stands on that plot, just one of many federally owned properties on the campus — including staff housing, office buildings, parking and storage lots, a university’s baseball fields, a high school athletic center, Army and Air Force facilities, a post office, and an interstate freeway — that do not principally benefit veterans.

This was not the first time Pacific Branch land was considered for nonveteran purposes. In 1912, branch officials ceded land to Los Angeles County to extend San Vicente and Wilshire boulevards. A Los Angeles Times article noting the transfer stated that the “regal boulevards” were “bordered by the beautiful lawns, shrubbery and graveled walks bespeaking the true manorial homeplace” — signs the tony adjacent neighborhood of Brentwood, “the perfection of suburban home places,” had arrived.

Later, in 1926, Congress explored the sale of 160 acres of the Pacific Branch to the State of California, which sought to establish a larger campus for what would become the University of California, Los Angeles. In return, the federal government would receive $1.5 million, which it could use to create fireproof barracks. Ultimately, UCLA struck a deal with a different landowner in 1929, cutting the ribbon on a Westwood campus abutting the Pacific Branch to the east. The 160 acres of Pacific Branch land later became a large part of the Los Angeles National Cemetery, which, as of 2024, has interred more than 90,000 veterans.

Four years after the scuttled deal, UCLA’s baseball team relocated from Westwood to the Soldiers Home, where Pacific Branch and American Legion-fronted teams played. The university continues to field its collegiate baseball team on the West LA VA campus as of 2024, while the veteran-associated clubs do not.

ADVENT OF THE VETERANS ADMINISTRATION

In July 1930, President Herbert Hoover signed an executive order to create the Veterans Administration, consolidating the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers and other veteran bureaus into one body. For the West LA VA specifically, which by then had swelled to 157 buildings serving around 3,420 veterans, the order would prove to be an opening jab in the forthcoming fight between veterans and the federal government over permanent housing on the campus.

During the Great Depression, Works Progress Administration programs kept development of the VA property rolling. Older buildings were razed and new ones — designed in the Mission Revival style in fashion at the time — were erected on a reorganized campus intended to provide modern standards of medical care. The changes proved to be shrewd: An influx of veterans from World War II led the VA to further expand the medical services available on campus. Replacing a tuberculosis ward built in the 1920s, the VA constructed seven neuropsychiatric hospitals on campus grounds.

As the 1940s drew to a close, the West LA VA’s hospital bed count outnumbered that of the domiciliary: 3,545 to 3,200. Women veterans also began receiving medical treatment on the grounds, with three wards providing care for around 500 women service members.

The VA also began to form associations between its hospitals and medical schools. In 1947, it formalized a medical research partnership with UCLA that took over four buildings on the north side of the VA campus. The following year, Congress passed another law allowing the VA to transfer 35 acres of the Soldiers Home property to the state of California through a quitclaim deed so UCLA could use it as a medical school. Its doors opened three years later.

“Our aim, actually, is to be in such proximity that we are actually almost one in operating in a very integrated manner,” Dr. Charles Modica, director of the Veterans Administration Center in Los Angeles, later testified to Congress in 1967.

Though health technology breakthroughs came as a result of the campus partnership — including the first nuclear medical scanner, the foundations of MRI and CT scanning to diagnose brain injuries, and research leading to the invention of the nicotine patch — veterans were subjects in sometimes risky research, including for illnesses as varied as alcoholism and epilepsy.

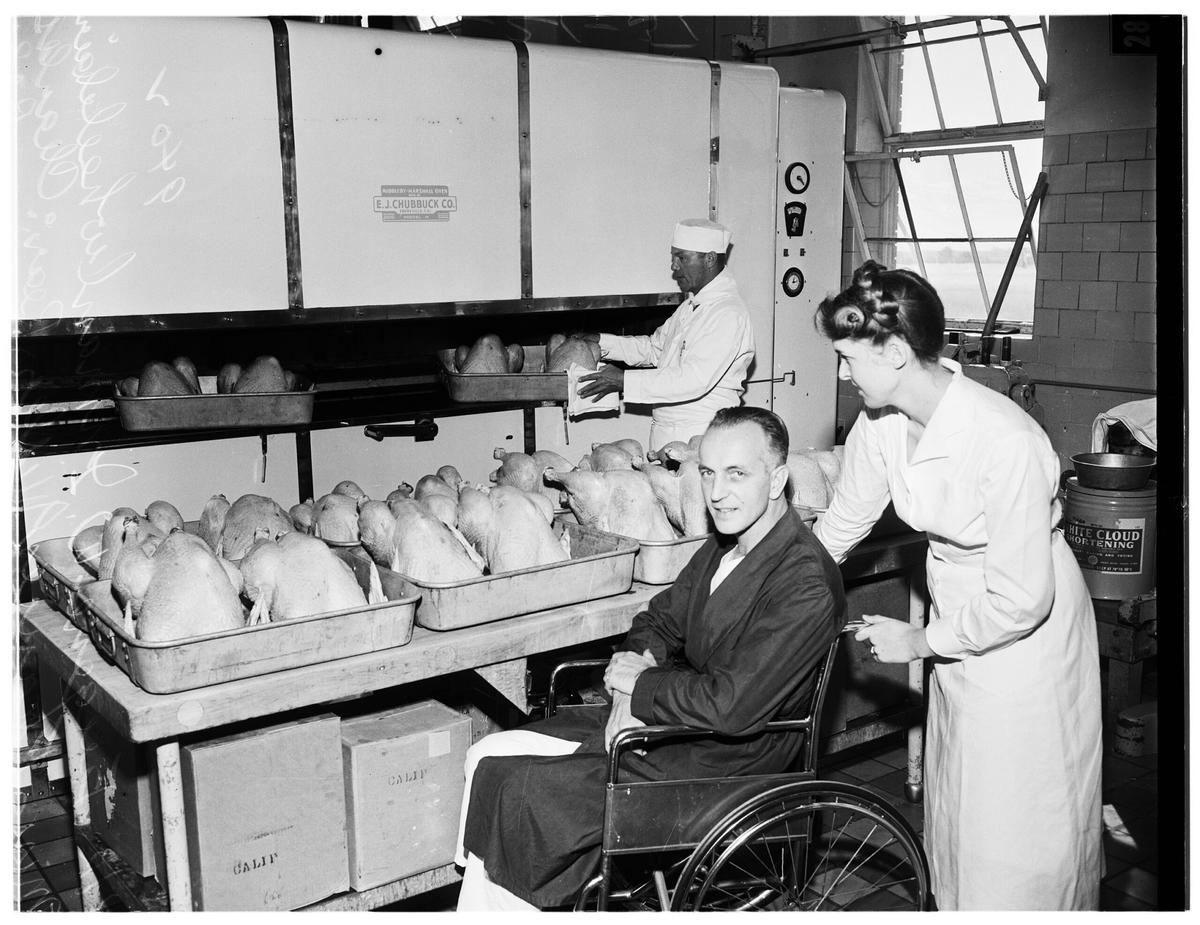

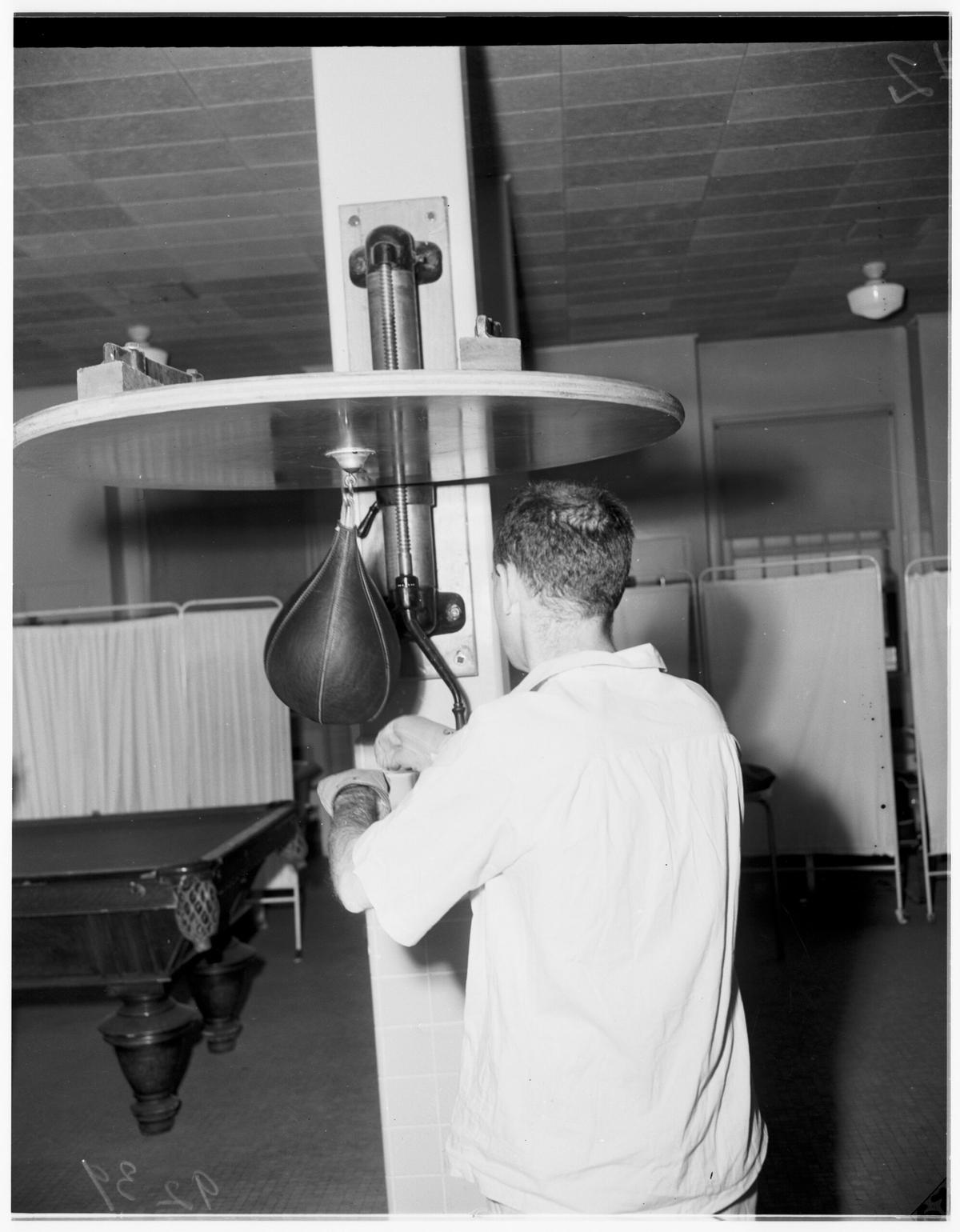

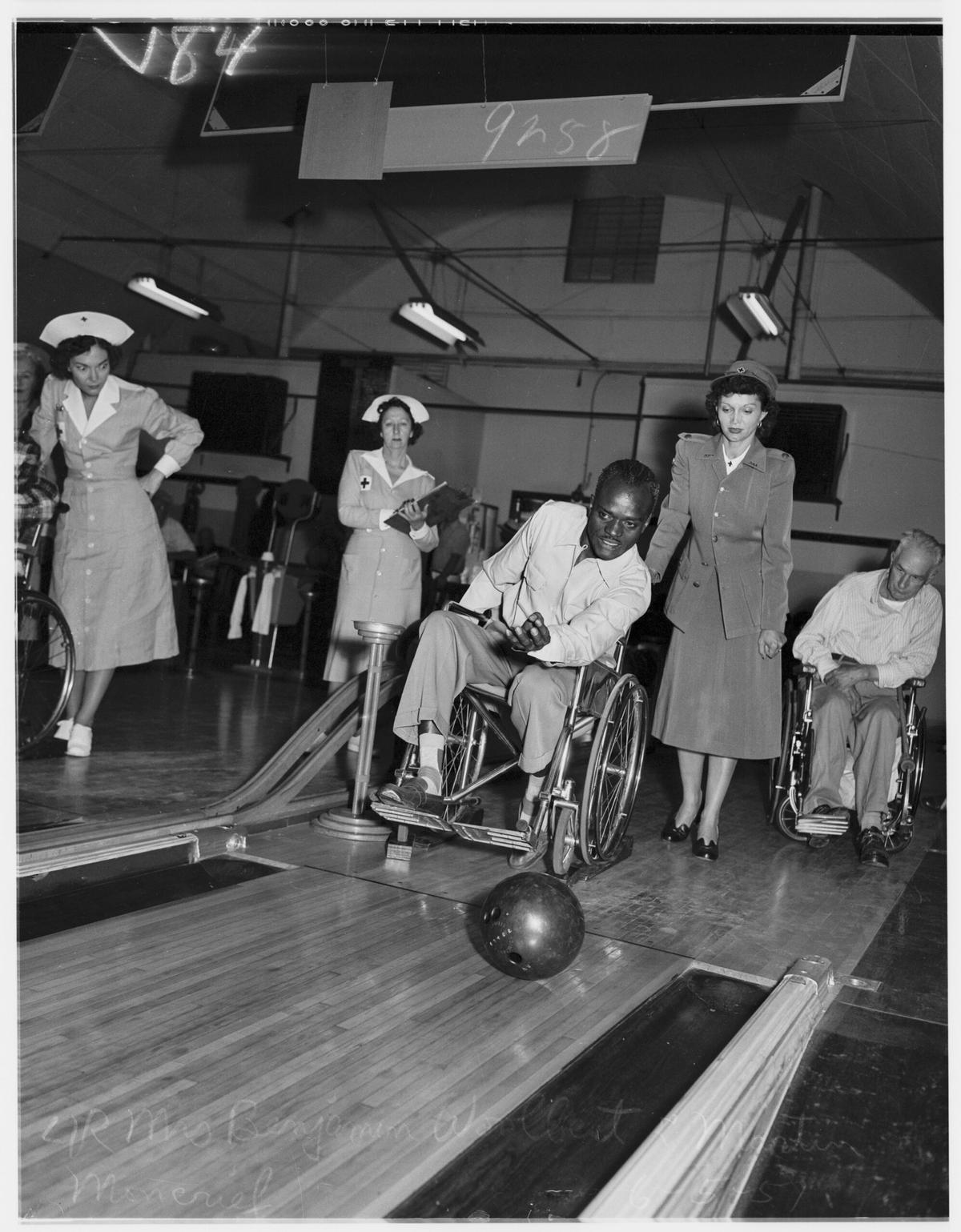

As postwar patriotism reached its peak and the VA was awash in resources, the campus offered a wide array of occupational therapies, including rug and basket weaving, book binding, and on-campus work programs. Residents had access to two theaters, three libraries, a softball field, croquet courts, a horseshoe pitch, and a nine-hole golf course — christened the Heroes Golf Course — that had been donated by nearby Hillcrest Country Club in 1946. In the 1950s, in the midst of the Korean War, the West LA VA saw its population top out at about 5,000 resident veterans.

But a landmark shift arrived in September 1958, when Congress formalized the VA’s evolving role by passing Public Law 85-857. The law established the comprehensive veterans’ benefits system that we know today — but also, according to Veterans Affairs, removed the VA’s authorization to build and manage permanent housing for veterans. Instead, the agency, and therefore its West LA campus, would narrow its focus to healthcare, cemetery services, and other benefits.

Neighboring institutions interpreted the change as an opportunity to use “surplus” VA land for their own purposes. UCLA campaigned for 44 more acres of VA land. Brentwood officials floated building a road through the property. A local official advocated for building a community park. By the early 1960s, none of these deals had materialized, but the borders of the Soldiers Home had begun to erode.

NO MAN’S LAND

The U.S.’s slow march into the Vietnam War dramatically altered the public’s view of veterans. Curdled by controversies in Southeast Asia and fueled by unsavory media depictions, sentiment had changed from people viewing veterans as All-American heroes toward seeing veterans as mentally scarred, prone to violence, and unfit for society. The communities surrounding the West LA VA were not immune to these opinions. In January 1972, Brentwood residents complained to the Los Angeles Times “that winos from the VA panhandle on the streets and litter lawns with empty pint bottles of Thunderbird and Triple Jack.”

While these stereotypes proliferated, many service members did struggle to readjust to civilian life after Vietnam, especially those who had inadequate public support to return to — a reversal from what veterans had experienced after previous wars.

Though service members who predated the 1958 policy shift still lived on the West LA property, new veterans weren’t allowed to live permanently on the grounds. Deteriorating conditions ensured they wouldn’t want to. In 1970, residents told the Los Angeles Times they were being indiscriminately searched and punished, repeatedly victimized by “strongarm robberies” on campus, and treated in buildings that had been condemned. The Times report appeared next to another story about a Senate subcommittee hearing that outlined how patients “often die unattended in their own filth” at the “medieval” Wadsworth Hospital, a 1,133-bed psychiatric facility that had been built in 1927. A doctor at the hearing displayed a photo of a sign on a wall that read, “Leaking roof. Move the bed when it rains.”

The Times report led to an inquiry from Sen. Alan Cranston, a California representative who headed the Senate Veterans Affairs subcommittee. Wadsworth doctors testified that several patients had died because of broken equipment and too little staffing. A director for the state’s nurses association said he “seriously doubts” the facility met accreditation standards. The center’s director, Dr. Modica, called the conditions “atrocious,” saying, “We’re giving subminimal patient care now and this situation is ready to explode as a major crisis.” Cranston demanded $174 million in increased VA funding, hounding the Nixon administration, which was loath to spend on veterans while being bogged down in Vietnam.

Everything changed on February 9, 1971. At precisely 6 a.m. local time, the 6.6-magnitude San Fernando earthquake rocked Los Angeles, destroying a Veterans Administration hospital in Sylmar, about 20 miles north of the West LA campus. Though the VA’s West LA buildings didn’t collapse, the Sylmar devastation triggered a review to determine the structural integrity of the West LA buildings. Thirty of them, including Wadsworth Hospital, were deemed uninhabitable and ultimately demolished. In January 1972, the VA ordered the approximately 1,500 veterans living on the grounds to vacate the property. They were given just one month to move out.

For the once-proud Soldiers Home, the earthquake proved to be a mercy killing. It snuffed out the congressional inquiry, buried the scandals, demolished decrepit structures, and sent remaining resident veterans packing for good.

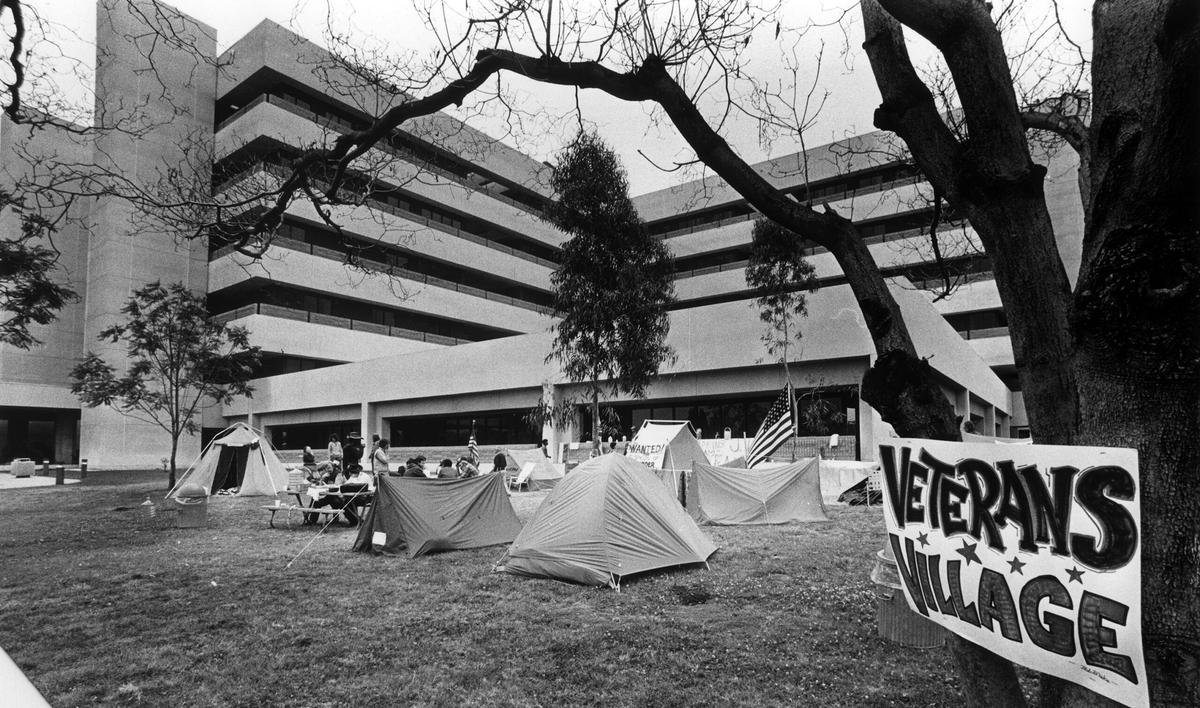

Where did they go? A 2015 congressional report on veterans and homelessness states, “In the 1970s and 1980s, the number of homeless persons increased, as did their visibility,” but it does not take responsibility for evicting veterans from land designated to house them. It does, however, state this telling government statistic: “The exact number of homeless veterans is unknown.”

Since then, for more than 50 years, unhoused veterans have been trying — vocally, fiercely, and in some cases in recent years, somewhat successfully — to again live permanently at the West LA VA. With fresh challenges to the government’s stewardship of this property winding their way through the courts, just 233 veterans live in permanent housing on the campus as of this writing. It’s a small army whose ranks pale in comparison to the thousands of veterans who once called this land home.

GET UPDATES FROM THE FRONT

Follow the veterans’ fight for housing at the West LA VA and receive court briefings from the trial.