The Old Guard and the New Fight

Relentlessly protesting the lack of housing on the West Los Angeles VA campus, a group of vets sparked a battle over the land’s misuse. But after a contentious legal settlement ended the dispute and failed to deliver much-needed homes, a new generation of service members is rising to continue their veteran revolution.

The American flag was hanging upside down — stripes up, stars down — just how Robert Rosebrock wanted it.

Standing at Landmark Gateway Plaza at the corner of Wilshire and San Vicente boulevards on February 28, 2010, the then 67-year-old veteran hoped drivers rolling past the West Los Angeles Veterans Affairs campus would see his flag, improperly hung, on the property’s wrought iron gate. He wanted them to know that on the vast property behind him, something was very wrong.

It was the 103rd consecutive Sunday protest outside the VA, a stretch that dated back nearly two years to March 9, 2008. In June 2009 Rosebrock had begun hanging the flag upside down to get the attention of passersby. The VA would eventually cite him six times for “unauthorized demonstration or service in a national cemetery or on other VA property,” but ultimately dismissed those rebukes. Still, the agency made clear to Rosebrock and his fellow protesters that they were not permitted to attach the upside-down flag anywhere on the government property — including its perimeter.

But when the Vietnam-era veteran did it again in February 2010, things changed. This time, after Rosebrock refused VA police’s demands to take the flag down, the officers removed it themselves. That’s when he decided to sue the VA for violating his First Amendment right to free speech.

The right to display a flipped over flag had never been Rosebrock’s point. It was what the distress signal represented — the veterans’ plight at the VA — that the former Army service member wanted to make known. “Our protest is an outcry that sovereign and sacred land deeded for the use and care of veterans is being stolen away and leased to private, special interest groups with no transparency or accountability for the money generated,” Rosebrock said in a 2010 statement. “The US Flag Code allows for the flag to be displayed upside down when property is in danger. It’s clear to us that this property is in danger and has been for a long time.”

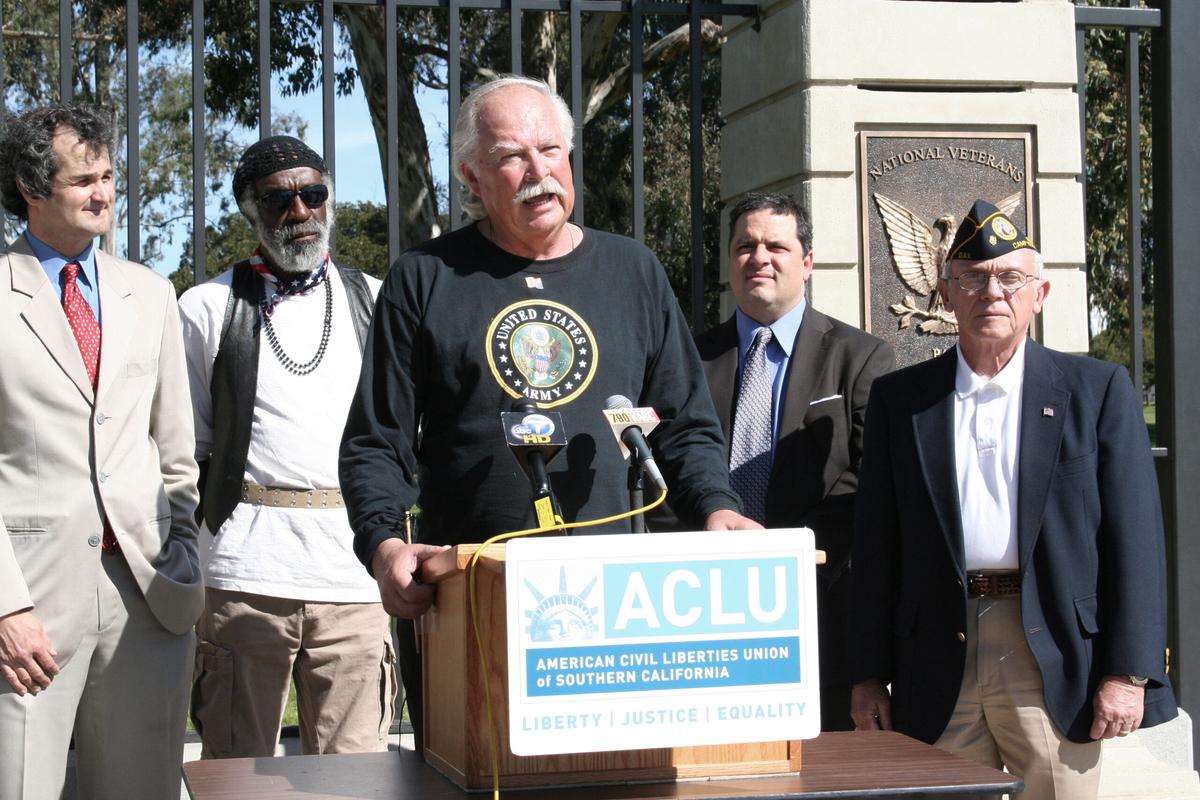

Ultimately, on May 27, 2011, a federal court ruled in favor of Rosebrock, backed by the American Civil Liberties Union, saying that the VA had violated his right to free speech. It was a hard-fought battle, but it wasn’t the war. That would begin 12 days later when the ACLU, buttressed by Rosebrock’s years of advocacy and research, filed another case against the VA, Valentini v. Shinseki — and it’s a conflict that continues to rage as of this writing, 13 years later.

Valentini v. Shinseki was a class action lawsuit that alleged the federal government had discriminated against homeless veterans with disabilities and misused the 388-acre plot upon which the West LA VA sits by improperly leasing it out to third parties and not providing permanent housing for veterans on the land, which its original deed mandated. The case was contentious and controversial, partly due to its many veteran stakeholders, Rosebrock among them, who disagreed with how it was handled by the platoon of lawyers who represented them — as well as their myriad conflicts of interest, real and perceived.

But progress was progress, and as the ACLU’s case worked its way through the legal system, Rosebrock and his band of protesters stopped signaling distress with the flag. “The flag-turning upside down worked,” says Rosebrock, now 81 years old, in a phone interview from his home in Indianapolis, Indiana. “We got a lawsuit.” But they did not stop protesting.

THE FLAG WAS STILL THERE

Rosebrock says he originally got involved at the West LA VA after 9/11. Like many Americans, he wanted to find a way to express his patriotism, and he did that through his involvement in activities on the campus. But, according to the former Brentwood resident, the more he became involved at the VA, the more his doubts grew about the property’s management and its treatment of veterans at the facility.

In March 2006, tensions among vets boiled over when the Veterans Park Conservancy, a nonprofit group that wanted to turn the property’s great lawn into a public park, engraved “Beauty, Honor, Country” in concrete by the gate at Landmark Gateway Plaza. The brass-plated wordplay was a twist on the U.S. Military Academy’s since-mothballed motto “Duty, Honor, Country,” which was nearly as old as the West LA VA campus, itself. The phrase landed poorly with many veterans; Rosebrock told the Los Angeles Times in 2006 he was “stunned” when he saw it. According to the Times, John Keaveney, a Vietnam veteran running an on-campus home for 220 homeless veterans, wondered “whether the $2.3 million spent on the gateway could have been put to better use helping disabled veterans.”

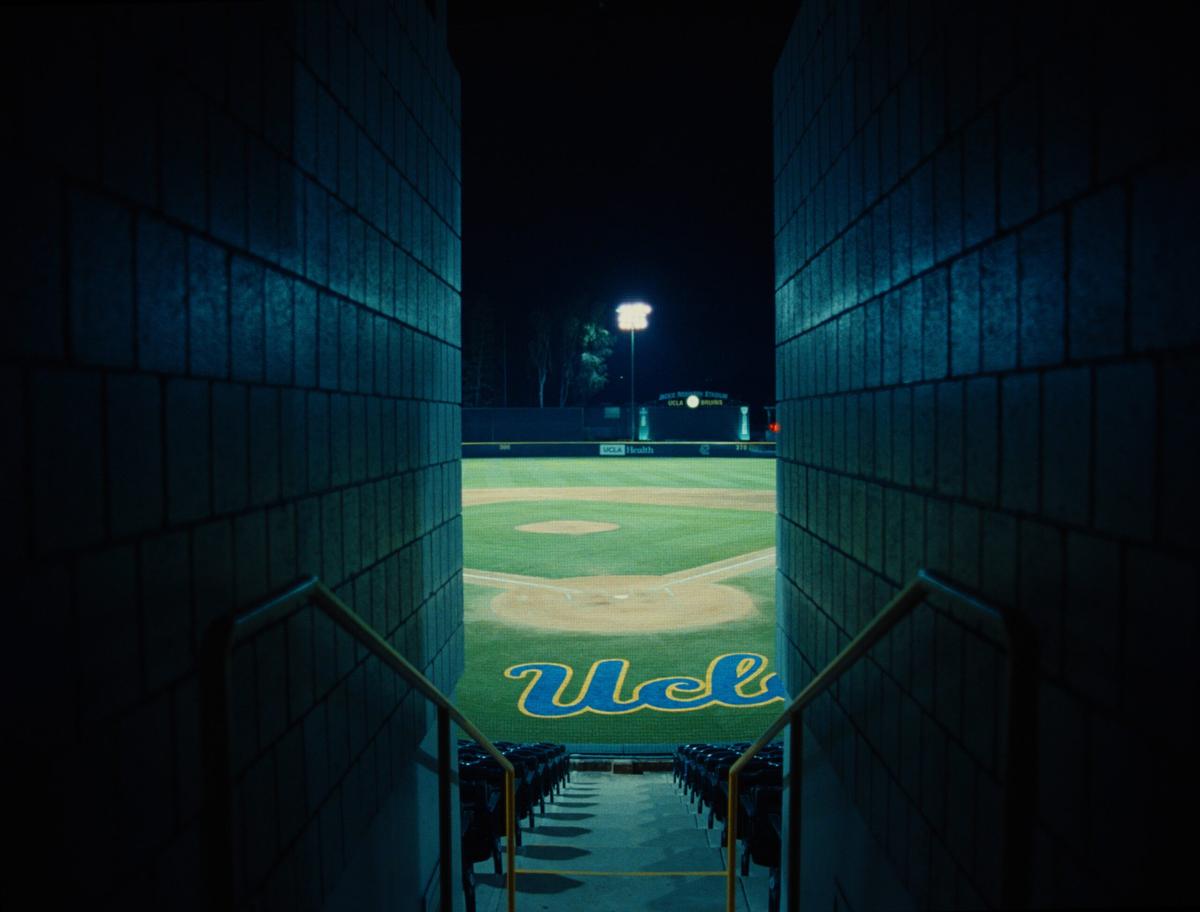

Keaveny’s sentiment cut to the core of the vets’ emotional wound as they had watched outside interests take control of the West LA VA across the decades. For instance, the 10-acre ballfield where veterans’ beloved American Legion teams once played had been controlled by UCLA’s baseball team going back to the early 1980s. Between 1998 and 2012, Brentwood School started a construction spree, spending an estimated $17 million to build athletic facilities on the 22 acres of land it had leased from the VA. And by 2007, VPC had secured a rent-free lease across the campus’s 16-acre great lawn, which it wanted to turn into a $7 million public park and amphitheater.

Meanwhile, there were signs all over the VA campus that the agency was failing in its mission: Still-standing Depression-era buildings were woefully inadequate (if they were even in use), and veterans suffering from conditions like post-traumatic stress were being discharged from short term treatment without a place to go — which meant they could end up living on the streets of Los Angeles.

Around 2008, Rosebrock says, he and some fellow Vietnam veterans teamed up with surviving World War II and Korean War service members to form what they called the Old Veterans Guard. Rosebrock describes the group as an ad-hoc team and takes pains to note that it’s not a nonprofit organization. “We chose not to make it a nonprofit because we didn’t want someone coming in, giving us $1 million and making us go away,” he says.

The group met and performed acts of patriotism, funding its efforts out of members’ own pockets. One such event was a gathering in the park — which Rosebrock says they had special permission from the VA to hold — that was broken up by campus police after attendees complained about the VPC and the property’s congressional representative, Henry Waxman, a Democrat from nearby Beverly Hills. According to Rosebrock, the VA police confronted the group and said it couldn’t voice political opinions in the park. In response, Rosebrock says, he announced to the crowd, “Next Sunday we start the veterans’ revolution.”

In all, the Old Veterans Guard went on to protest for 801 consecutive Sundays at the corner of Wilshire and San Vicente boulevards. Sometimes the protests consisted of just one vet; other times experienced demonstrators from the VA hunger strikes in the 1970s, like Ron Kovic, showed up. But for more than 15 years of Sundays — rain, shine, or holiday — there was always someone on post at the VA’s gate.

Shortly after the January 2015 Valentini settlement, in which the two sides agreed to a new master plan for refurbishing the VA campus and building 1,200 housing units, Rosebrock went back to attaching the flag to the VA’s fence. He figured he had cooperated long enough; it was time to get back to raising awareness of conditions on the campus. One specific concern the vets had was the leasing out of the lawn to the VPC. Rosebrock and others believed it should have been used as a shelter for unhoused veterans. After months of veterans protesting in this way, VA police again came out and asked Rosebrock to take the flags down, which he again refused to do, so they cited him. Sunday after Sunday, he incurred more citations, and after each one, he had to appear at the LA County courthouse. Representing himself each time, he got them dismissed.

According to Rosebrock, because he didn’t draw benefits like disability from the VA — he did not see combat during his service — he could keep protesting in this way, and the VA had no recourse. “We have veterans who didn’t want to come out there because they were afraid of being seen holding a flag or something,” Rosebrock says. “I had [the VA] over the barrel, and I knew it.” Fear of the VA remains a problem among veterans; multiple sources connected to the VA refused to go on the record for this story, over concerns of reprisal.

Eventually, Rosebrock was handcuffed and had his camera confiscated after a trio of citations starting on Memorial Day 2016 for placing small flags on the VA fence and taking photographs of them without permission. In court, the VA’s attorney protested that Rosebrock was operating without legal representation. Though he had gotten many cases dismissed prior, Rosebrock was facing prison time for these most recent alleged criminal acts. A trial was set for December 2016, and the judge said the court would assign him counsel. That’s when Rosebrock connected with Judicial Watch — a legal group that is the ideological opposite of the ACLU — and it arranged for him to have an attorney. The case was dismissed on April 18, 2017, appealed by the government a year later, and dismissed again by California’s Central District federal court. Afterward, Rosebrock told the local NBC affiliate that he felt “honored that the flag was exonerated — and for once the veterans got a victory.”

DOWN ON THE CORNER

As trivial as the VA’s charges against Rosebrock seemed to be, and as low-stakes as the Old Veterans Guard’s weekly flag-waving protests appeared, there was a weighty undercurrent to this conflict: The government wanted to assert its control over the land, and the veterans were not going anywhere. But the slow development of veteran housing at the West LA VA following the Valentini settlement would soon haunt parties on both sides of the fence.

As years ticked by after the settlement, more veterans were gathering on San Vicente’s sidewalk — and they weren’t just members of the Old Veterans Guard. From the group’s perch on the corner, they could see unhoused veterans coming to live on the street. Rosebrock remembers some of them first taking refuge in the shrubs along the VA’s fence. Eventually they brought their belongings. Then they started building makeshift structures.

Rosebrock recalls a Marine veteran named Andre Butler arriving in 2018, perhaps earlier. The two got to know each other and learned about each others’ lives. One time, Rosebrock said Butler “used to be” an engineer. “I still am,” Butler reportedly replied. “I just haven’t had a job.”

One day, a city crew came through to “sweep” the sidewalk, move the unhoused veterans along, and throw away any items they left behind, Rosebrock says. Butler, who previously had mobility issues, resisted and an LA County sheriff’s deputy detained him. After being placed in the deputy’s car, Rosebrock says, Butler kicked the window. Six months later, Rosebrock says, Butler returned to San Vicente, only then he was using sticks for crutches. Butler is now deceased, allegedly stabbed to death in September 2021 by another unhoused veteran while they both lived on San Vicente.

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit in early 2020, even more veterans flocked to that sidewalk to live near VA services that they needed to survive. As the crowd grew, conditions worsened and the protesting veterans on the corner came to their aid. In April, Rosebrock wrote an editorial published by the American Legion, noting that “for years, we have been respectfully requesting public portable toilets and showers for the homeless Veterans living directly outside the Los Angeles VA but have been repeatedly rejected. Now they are bowing to the federal judge’s order and providing these humanitarian facilities inside the VA and veterans who sign away their life and freedom can live in a pitifully small ‘pup tent’ and have access to public toilets and showers — only during the virus lockdown.”

The VA effort that Rosebrock was referring to was the Care, Treatment, and Rehabilitative Services program. CTRS, or what the Los Angeles Times called a “tent city,” initially provided 25 tents in a VA parking lot, with room to double that count if needed. According to a local NBC News report at the time, a VA spokesperson said that vets didn’t need to live in tents — that they were choosing to do so and that there was transitional housing available to former service members who wanted it.

But, NBC also reported, the agency was not permitted to provide food for the vets in the tents, because the vets weren’t technically residents of the campus — which left nonprofit groups like Village for Vets, operating out of the Brentwood School’s kitchen, to make three meals a day for those in need. Meanwhile, the Times was reporting, a bridge shelter was indeed open on the campus, but with social distancing it could only accommodate 50 people. Plainly stated, the VA, like many institutions during the pandemic, had been caught flat-footed by the crisis and stretched thin by its demands.

Many vets were reluctant to move into CTRS, despite the access to medical, behavioral health, and housing services that the VA was providing inside the property’s gates. Living on the campus meant abiding by its many rules: Vets who wanted to overnight on the VA campus had to arrive before 2 p.m., recalls one advocate who was helping to connect the homeless vets to housing resources, and could not leave the property until the morning. Also, the tents that were provided, initially set up on an asphalt parking lot, were small and good for little more than lying down and sleeping. Veterans with mobility issues would not be able to enter or exit them without assistance.

Like Village for Vets, Rosebrock and his fellow vets tried to fill the gaps. According to his American Legion editorial, the Old Veterans Guard “offered to provide 14×10 walk-in tents with cots so the veterans would not have to sleep on the cold and damp asphalt. As would be expected, the VA rejected our offer and instead created a fenced-in, imprisoned, skid row-like internment camp directly inside the VA.”

In response, he announced, the Old Veterans Guard would create “a new mission by upgrading the fenced-off area directly outside the VA into a patriotic ‘Veterans Pride Row’ that will include American and U.S. military branch flags.” Rosebrock says he bought the first tent, his sister and brother-in-law bought the second, and Judicial Watch and Marine veteran James Spencer bought more. The first eight uniform tents were erected on San Vicente less than two weeks after the VA’s CTRS was announced, and the Old Veterans Guard planned to buy and install dozens more. “How we’re approaching this is more on the Golden Rule. If you were homeless what would you want somebody doing?” he told Spectrum News a month later. “And that’s what we’re trying to do.”

GROUND CONTROL

When Jeffrey Powers first saw the West LA VA in July 2020, the sprawling campus seemed like a paradise: temperate weather, historic Mission Revival-style buildings, and lush parkland. The campus was only made nicer by its central location in the city — prime real estate right beside the upscale neighborhood of Brentwood, with all its tony amenities. But the Navy veteran soon found that despite the ample space, the land lacked the thing he needed most: housing.

Upon arriving at the campus, after he cleared COVID testing, he was sheltered in a tent at CTRS and then was rescreened for the virus twice a week. “The fear was that the unhoused population out on the street was the highest-risk population,” Powers says. “So the VA was actually trying to do something to help veterans avoid getting COVID, which I give them props for.”

The day after Powers arrived at CTRS, the VA moved the occupied tents — which Powers estimates numbered under a dozen — from the asphalt parking lot to the grass, where there was shade. It was a relief from the hot summer sun, but it didn’t necessarily improve conditions in the small tents. Powers says he had a problem with his knee that was being aggravated by the getting up and down to exit the shelter. Organizations and private donors “offered the big tents that you could stand up in, but [the VA] refused to accept them,” he says. “The ones they gave us were — they call them three-man tents, but if you got three people in there, they’d better be skinny.”

And then came the gophers. One night Powers was sleeping in the tent, which was erected on a tarp over the grass, with his sleeping bag under him for cushion. “I’m sitting there and I see this little thing is just bumping against the sleeping bag.… I reached out and I touch it and I’m like, ‘Oh, what is that?’” Powers pulled back the sleeping bag to discover that a gopher had chewed through the tarp and the tent and was now inside the shelter with him.

Powers told the VA officials about the gopher, and they decided to put the tent on a palette to keep the animals out. When they showed him his new accommodations, Powers noticed something else had changed: The tent was smaller, down from a three-man to a two-man shelter. In September 2020, Powers got a room at a local Motel 6 and then fell into a labyrinth of bureaucracy that included seven case managers as he was shuffled between various sheltering options, agencies, and voucher programs all around the county (and took a trip back home to Phoenix) until he ended up where he had started: CTRS. After resettling there, he left the campus to stay at a friend’s apartment for a weekend. When he returned to his tent, he found a rat sitting on his cot eating a granola bar. “I just lost it,” says Powers, who ended up tearing the tent apart to get the pest out. “That’s when they decided that I should leave CTRS,” he says.

Powers left CTRS and found a home at Veterans Row, as the residents had begun calling the sidewalk encampment. That’s where he and other veterans began to learn about the history of the West LA VA from the generations of vets who had protested on the campus before them. They learned how the land had been donated to the federal government in 1888 to serve as a home for disabled veterans, how about 5,000 former service members called the campus home at its peak, and how the housing fell into disrepair as the VA shifted from housing to health care, starting in the late 1950s. They also learned about the improper leases, the Valentini case, the settlement that hadn’t yielded housing — all of it.

And from veterans like Rosebrock who had protested on San Vicente for decades, they were being told who to blame for all this misfortune: the lawyers.

CONFLICT ZONE

When Mark Rosenbaum is in the classroom instead of the courtroom, one of the first things he teaches his students is not to be a “paratrooper lawyer.” “It’s not about getting notches on your belt; it’s about actually bringing about social change,” the 76-year-old civil rights attorney says.

With a five-decade-long career that has included four appearances before the Supreme Court, blocking the Trump administration’s efforts to end the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, and reversing the murder conviction of Black Panther Geronimo Pratt, Rosenbaum’s belt has plenty of marks. Among them is the 2015 settlement negotiated with the federal government in Valentini v. Shinseki, in which the VA promised to provide housing and end illegal leases on the West LA VA campus. Rosenbaum looks quite differently at that case now, describing the settlement as “the worst mistake in my career, bordering on malpractice.”

While Rosenbaum takes responsibility for what he sees as the shortcomings of the settlement, his name and signature do not appear on the document. Rather, his co-counsel, Ronald Olson, cofounder of the white shoe firm Munger, Tolles & Olson, was the lead negotiator on the agreement with the government. Olson has long been well-connected in both Los Angeles and the legal profession generally. He has served as a member of the UCLA Stein Eye Institute board since 1995 and has worked as the general counsel for both California’s Democratic Party and former Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger, a Republican.

Olson, whose firm had worked with Rosenbaum on other civil rights cases, first became involved in the VA suit at the urging of Santa Monica Mayor Bobby Shriver, another lawyer on the case. Shriver did not respond to requests for an interview.

At first, the government fought the case with surprising gusto — “like the vets were terrorists,” Rosenbaum says in a phone interview. In 2013, a federal judge ruled that the VA had, in fact, violated the law by leasing out the land to commercial interests, but the government vowed to appeal the ruling.

Before the appeal could be heard, reports of systemic delays in care at VA medical facilities across the country resulted in the 2014 resignation of VA Secretary Eric Shinseki. In his place, President Barack Obama appointed Robert McDonald, a West Point graduate who had reached the rank of captain before striking out for the private sector, where he became the president, CEO and, ultimately, chairman of Procter & Gamble. McDonald says news of the lawsuit came as a surprise to him when he took over the position.

“I was working on homelessness, which was a priority for the president,” McDonald says. “The number one place for homelessness in the United States is Los Angeles, and so I scheduled a trip to go to Los Angeles and our general counsel says, ‘Well, you can’t go there, because we’re being sued.’”

McDonald got hold of the complaint against the VA and saw a familiar name, Ron Olson, who had worked as Warren Buffett’s attorney during McDonald’s time at Procter & Gamble. Buffett was the largest shareholder of the Procter & Gamble Company.

Interviews with key players involved in crafting the settlement suggest the relationship between Olson and McDonald raises questions about conflict of interest. McDonald refutes this claim, citing the number of parties to the negotiation — including Shriver, the ACLU, and veterans groups — ensured there was no conflict. “It wasn’t just Ron and me in some smoke-filled room,” he says. Olson describes their familiarity as the foundation of a mutual trust. Because of that relationship, Rosenbaum says he took a backseat during the negotiations, allowing Olson to lead on behalf of the vets.

The results of those negotiations, outlined in the “Principles for a Partnership and Framework for Settlement,” called for the VA and the lawyers for the vets to “work together in good faith.” That included the drafting of a master plan laying out appropriate uses of the land, with an emphasis on “bridge housing and permanent supportive housing.” It also dictated that both parties “[d]evelop an exit strategy” for the illegal leases, so long as the strategies “present a minimum level of litigation risk and expense to the Government.”

The second to last item in the settlement — the provision that would come to haunt Rosenbaum — held that “[t]he Principles Document is not to be enforceable in any court.”

Olson and McDonald signed the document on Jan. 28, 2015.

Olson recalls the issue of enforceability being a “sticking point” for the government. “The government did not think they could give away, in a settlement, the authority that we were agreeing to in that settlement,” he says.

McDonald, meanwhile, suggested that the enforceability of the settlement would not have made a difference to its outcome. “The court doesn’t build houses for veterans,” he says. “The fact that there was a lawsuit got my attention, but you could also get my attention by Ron or Bobby or Mark picking up the phone and calling me. Now, maybe that’s not working with the current guy. I don’t know, but that’s what you do.”

Without the ability to enforce the terms of the settlement through the court, however, veterans had no recourse once problems began popping up.

SETTLING FOR NOTHING

Months after the settlement, freshman Congressman Ted Lieu introduced a bill to authorize the settlement agreement. The bill, eventually renamed the West LA Leasing Act, would empower the secretary of the VA to enter into third-party leases for housing and services that “principally benefit veterans and their families” and adhere to the master plan.

In a congressional hearing, Lieu touted the public-private partnership housing model — also known as enhanced-use leases — as “[t]he best vehicle for the development of this housing.”

But the reliance on outside developers for housing introduced new problems for veterans. Los Angeles housing officials highlighted these issues in a letter to the city’s mayor, Karen Bass. “In order to build affordable housing, developers apply for funding from multiple sources, including City, County, State and private financial institutions, each of which may have different eligibility restrictions tied to its funding,” the letter states. “In order to be competitive for public funding, developers often agree to the most restrictive income limitations, generally the 30% [area median income] level.”

Under the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s policy, disability payments count as income. This has created a situation where disabled veterans — those most in need of housing — may make too much to qualify for the housing built for them. For instance, to receive a housing voucher from HUD, a veteran cannot make more than $48,550. But vets who are considered 100% service connected disabled receive $44,854 a year, meaning additional benefits or income totaling more than $3,696 tip them into ineligibility.

At 62-years-old, Powers, who now lives in one of the VA’s newly renovated units, is eligible for Social Security payments.

“My income will be too high once I start Social Security, and I will have to leave here,” he says.

McDonald says that having the VA build the housing itself would have required Congress to allocate the necessary funding. “To do it through Congress would just take forever, and you’d be [a] prisoner of the politics, left and right,” he says.

Rosenbaum pushed back, pointing to the VA’s $336 billion budget already green-lit by Congress and saying that “to build 1,200 units would be chump change compared to that.”

Problems also arose with the West LA Leasing Act around the illegal leases on the VA grounds. While the settlement promised to remove “non-VA entities” that did not “comply with applicable law,” the West LA Leasing Act provided a caveat for UCLA.

The university had decried the 2013 ruling that invalidated the lease for its Jackie Robinson Stadium two months after the school won the College World Series. Lawyers for the school complained in court filings that the ruling “would render UCLA’s championship-winning team homeless by the start of its next season.”

But under the terms of the West LA Leasing Act, the VA may lease land to UCLA so long as the “predominant focus” of the university relates to services for veterans and the university provides “additional services and support” over the term of the lease. While Jackie Robinson Stadium is not explicitly named in the text of the law, it was widely understood to be the subtext.

In a congressional hearing about the bill, then Michigan Rep. Dan Benishek characterized the provision as a “carve out,” which Lieu denied, insisting that “it simply authorizes the VA secretary, if he wants to, to approve this lease.”

McDonald, for his part, says he saw no reason to kick UCLA or Brentwood off the campus. “I had no use for that land anyway. So, for me, it was more interesting getting fair market value for that and something that would benefit veterans,” he says.

In the case of Brentwood School, in order to fulfill its obligations under the new law, the school allowed veterans to use the athletic facilities at designated times. Brentwood also extended scholarships to the children of veterans and donated tiny homes for temporary shelters. “While vindictive people would say just throw them out, to me, it didn’t make any sense to throw them out if I didn’t have a good use for the land,” McDonald says.

But in 2018, the Office of the Inspector General issued a scathing report that undermined the cooperative vision laid out by McDonald, finding that UCLA and Brentwood School paid dramatically less than the independently appraised value of land. The report further found that Brentwood School violated its lease terms under the Leasing Act, citing figures showing that only 67 veterans had used the athletic facilities. In 2021, the OIG again found that Brentwood was still not in compliance with the West LA Leasing Act.

Despite promises of transparency and inclusion, the report faulted the VA for failing to include veterans and veteran groups in discussions on how to improve the campus following the 2015 settlement, prioritizing groups that “represented the public at large versus veteran interests.” Specifically, in developing the draft master plan that would dictate the future of the property, the VA “focused largely on political partners and neighborhood councils.”

Rosenbaum expressed doubts about the commitment of elected representatives to the goal of building housing. In early meetings with Sen. Dianne Feinstein’s and Rep. Henry Waxman’s offices, prior to filing the 2011 lawsuit, he says that both of them “drew the line” at housing veterans on the campus.

“They let it be known that community homeowners had opposition, and they wanted to know why there wasn’t other solutions as well,” recalls Rosenbaum.

Rosebrock had already been howling about Waxman for years. “One member of the California Democratic Party brought disgrace upon the entire Party by turning his back on 20,000 homeless Veterans and blocking a resolution on their behalf, while defending the Westside Machine’s wealthy constituents who live in multi-dollar homes,” the veteran wrote in an editorial in 2008.

In 2015, months after the VA signed off on the settlement, according to Brentwood News, Lieu told a group of local neighborhood councils, including Brentwood’s, that “it neither makes sense nor is it the VA’s objective to have the campus become the depository for large numbers of homeless veterans,” according to a summary of the meeting.

“[Lieu] pointed out that housing is not in itself a solution,” the report states.

The master plan set a goal of 1,200 units by 2026. As of May 2024, the VA had built only 233 units — far short of the 770 projected by the department by that time.

While Olson, one of the architects of the settlement, expresses disappointment about the rate of progress, he continues to stand behind the settlement. “There’s no question in my mind that the settlement was a net positive,” he says.

ONCE MORE INTO THE BREACH

With the sense that the case remained “unfinished,” Rosenbaum met with Rob Reynolds down the street from the West LA campus at the Coral Tree Cafe several months before filing a new lawsuit on November 15, 2022. An Iraq veteran, Reynolds had developed a reputation for wrangling the unhoused veterans first on Veterans Row and then on CTRS, which had since transformed from being a pup tent encampment to a village of 147 tiny shelters with electricity and air-conditioning. Though Reynolds had worked with Rosebrock around Veterans Row’s founding, the two no longer saw eye to eye, a discord similar to those found among prior generations of service members who couldn’t identify with each other’s experiences.

Acutely aware of the veterans’ dissatisfaction with the outcome of the settlement, Rosenbaum acknowledged the mistakes of the first suit. “You have no reason on the planet to trust me,” he remembers telling Reynolds, “but I want to do my part, and I think a new case should be filed.”

Rosebrock was not party to the conversation with Reynolds, but holds Rosenbaum accountable for the inadequacy of the first settlement and its failure to produce any substantial improvements for vets on the VA campus. “I was on record going after him afterward; I said you never, ever honored that settlement,” he says. “Rosenbaum wants to go in and try to clear up his name because they screwed up bad.”

But the rare admission of responsibility earned Reynolds’ trust, and within a few weeks, Reynolds gathered Powers and other veterans in a park to meet Rosenbaum and his team.

Rosenbaum’s new lawsuit was filed against VA officials, HUD, and the Housing Authority for the County of Los Angeles, or HACLA. Though suing the VA for failing to provide supportive housing, the suit takes wide aim at the byzantine system of benefits that has grown around the country’s former service members — a system that Rosenbaum and veterans say has, by design or by accident, evaded responsibility for its charges by virtue of its own bloated bureaucracy.

Summarizing the two decades of legal and political strife over the property leading up to the moment, the complaint opens, “Despite a lawsuit, two Acts of Congress, and two reports of the Office of Inspector General detailing the VA’s failings, Defendants are leaving thousands of veterans to live and die on the streets of Los Angeles.”

The complaint advanced the argument that the 1888 deed donating the land to the federal government established a trust on behalf of disabled veterans. The government violated its fiduciary duty to veterans by failing to provide housing, the suit argues. Furthermore, it violated the West LA Leasing Act by entering into land deals that did not “primarily benefit” veterans, such as those with Brentwood School and UCLA.

Unlike in the 2011 case, the government immediately reached out with interest in discussing a settlement. The negotiations stretched on for several months, according to court records, at which point the government presented its final offer. Rosenbaum could not share the terms of the offer, but said that it contained restrictions so severe as to make it dead on arrival. The federal government would not commit any resources, would not build on the land and would not ask Congress to pass legislation that would authorize construction, he says of the offer.

Another participant in the negotiations confirmed Rosenbaum’s account but requested anonymity before discussing sensitive legal matters. Instead, he says, negotiators told Rosenbaum that they hoped that he and the veterans would go to Congress themselves and ask for funding and housing.

“We said, ‘OK, we’re just going to go to war,’” Rosenbaum says.

“EVERYTHING IS ON THE TABLE”

The government soon filed a motion to dismiss the suit entirely. As Rosenbaum and his team were preparing to fight the government’s motion, they learned that the case had been assigned to Judge David Carter — a promising development for the veterans and a blow to the government.

In over two decades on the federal bench, Carter has garnered a reputation as a colorful — albeit serious — jurist with a streak as an advocate for the unhoused. He runs his courtroom with an, at times, theatrical flair and has conducted courtroom proceedings on Skid Row and at other homeless encampments.

But Carter comes to this case with even more background than that, he made clear in a handful of disclosures in court. He shared “a disclosure I rarely make”: that he had served as a Marine in Vietnam and spent a year in various hospitals after sustaining a gunshot wound. He even had personal familiarity with the West LA VA campus. As a cross country runner at UCLA, he had trained throughout the VA complexes, which, he noted, constituted trespassing.

“But the statute has passed,” he added.

In September 2023 at the First Street U.S. Courthouse in Downtown LA, parties for both sides gathered for the hearing on the motion to dismiss. A handful of veterans, including Reynolds and Powers, sat in the gallery. From his seat on the dais, Carter remarked that they were in the same courtroom as the 2011 case.

“The obvious question is: What happened?” Carter said to Department of Justice trial attorney Zachary Avallone.

Avallone conceded that the original construction timeline of 1,200 units by 2022 was “unrealistic” and that environmental reviews and needed improvements to the infrastructure created significant delays, but Carter voiced his general frustration with governmental obfuscation.

“We couldn’t cut through the federal bureaucracy to speed that process. We in the federal government?” Carter asked. “I understand the segmentation of the federal government. But I don’t have much patience with the argument that we’re all segmented.”

To Powers, sitting in the gallery, Carter’s directness came as a relief, a chance for a public airing of nonsensical experiences like his. The veteran struggled to understand, for instance, why he had to submit the same materials to three different agencies to get housing — first to HUD’s Veteran Housing Supportive Housing program, which certifies him as a disabled veteran and disburses vouchers for supportive housing; then HACLA, the local housing authority, which goes through its own certification process; and then Step Up, the nonprofit that manages his unit, which also goes through its own certification process.

“This is the 21st century. There’s no reason that this should not be in a central database where all the different agencies can go and get the same information,” Powers says.

Showing a degree of skepticism himself, Carter questioned the arrangement between federal and local agencies, asking the attorney for HACLA why the VA doesn’t distribute housing vouchers itself.

“Because, I would imagine, the bureaucracy involved with trying to deal with this from D.C. would be less than efficient than having local housing authorities involved in this,” the lawyer responded.

Carter pressed: “Doesn’t that segmentation allow, in a sense, non-accountability?”

But Carter went into the hearing with a predrafted, tentative ruling before either side had argued its points. Much like the judge before him in 2011, Carter’s tentative ruling split both ways, for plaintiff and defendant, finding that the leases with UCLA and Brentwood School violated the West Los Angeles Leasing Act, but that the VA did not have a legal obligation to provide housing.

But Rosenbaum had come to court with a novel argument, one that drew from disability law and argued that the VA had discriminated against disabled vets who could not access care without permanent supportive housing. In Rosenbaum’s argument, housing was akin to a wheelchair ramp. Afterward, Carter announced that he had to “rethink the entire jurisprudence and the research I’ve put into this.”

“Everything is on the table,” he said.

In a ruling issued in December 2023, Carter ruled in favor of the veterans on every count. The ruling does not obligate the VA to construct housing or evict any leaseholders, but it sent the case on path toward trial. In court to issue the ruling, Carter pressured both sides to resolve the conflict in mediation.

“If you can’t settle, then we’ve got a date,” he warned.

Even while Carter noted the gravity of the problem, Powers feels its urgency all the more acutely. In late January 2024, he received a letter from Step Up notifying him that he was “ineligible for further housing assistance payments.” While he had successfully filed paperwork to prove his eligibility with HUD and HACLA, he had missed a deadline with Step Up.

But he remains committed to the lawsuit. “I don’t expect to get anything out of it myself,” he says in a phone interview from his apartment on the VA campus. “But there’s more that can be done for the people that come after me.” Much like when he joined the Navy at age 18, he’s fighting to be a part of something bigger than himself.

GET UPDATES FROM THE FRONT

Follow the veterans’ fight for housing at the West LA VA and receive court briefings from the trial.