Carving Up the Map

After prohibiting veterans from living permanently on land donated to house them, the VA entangled itself in a wild array of leases on the valuable Los Angeles property — from soccer pitches to parrot sanctuaries — inhibiting the government from solving a homeless crisis of its own creation.

In a car-forward city like Los Angeles, parking spaces hold special currency. Unlike New York City, its metropolitan rival to the East, it has a glut of spots. Across Los Angeles County, there are 18.6 million — or two for every man, woman, and child.

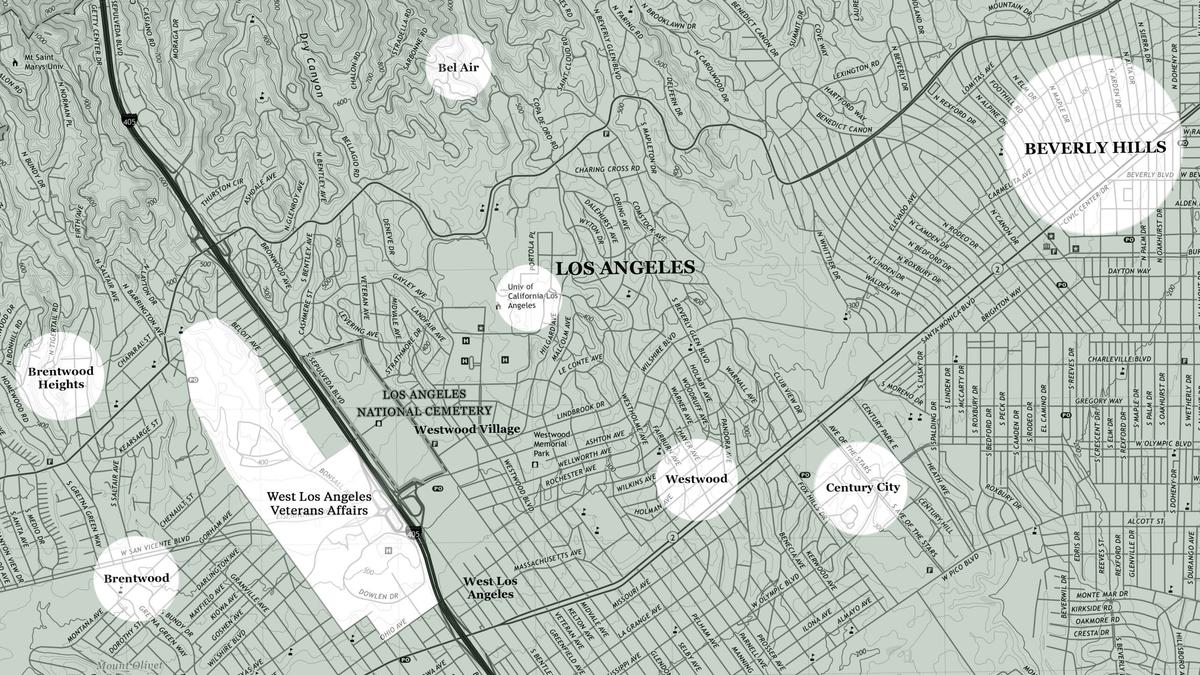

This surplus contrasts sharply with Los Angeles’ housing stock. The county government estimates it is short a half-million units, yet car lots continue to be carved out of prime, developable land — a phenomenon that played out in stunning fashion across the campus of the West LA VA, a 388-acre property that dates back to 1888, when the land was donated to the U.S. government to house disabled veterans. It’s a tale of greed, lies, and lost priorities that, in its betrayal of veterans, exposes just how valuable the campus land, sandwiched between the wealthy Brentwood neighborhood and prestigious UCLA, has become.

Over the last two decades or so, a diverse array of private interests secured parking spots across the campus, which, for much of this time, seemed perpetually stuck in redevelopment limbo. One was the 1887 Fund, a nonprofit focused on rebuilding an old chapel on campus, which secured three spots for its leaders. The City of Los Angeles gained an entire lot. A Brentwood businesswoman secured spaces for local shoppers. The biggest prize went to David Richard Scott, the bespectacled man who owned a parking company called Westside Services LLC. Scott, who had a background in parking lot management and limousine services, was handed hundreds of spaces — an asphalt jackpot that made him rich beyond his wildest dreams.

Scott first secured his parking contract with the VA in 1999. He negotiated the details with Ralph Tillman, a white-haired contract officer with decades of VA service under his belt. Unlike Scott, Tillman was a military veteran, serving in the U.S. Army for three years before being honorably discharged in 1977. The deal they struck made Westside Services the de facto proprietor of 450 spaces spread across four rolling acres. In exchange, Westside agreed to pay the VA $7,500 in monthly rent, plus about 60% of the gross revenue.

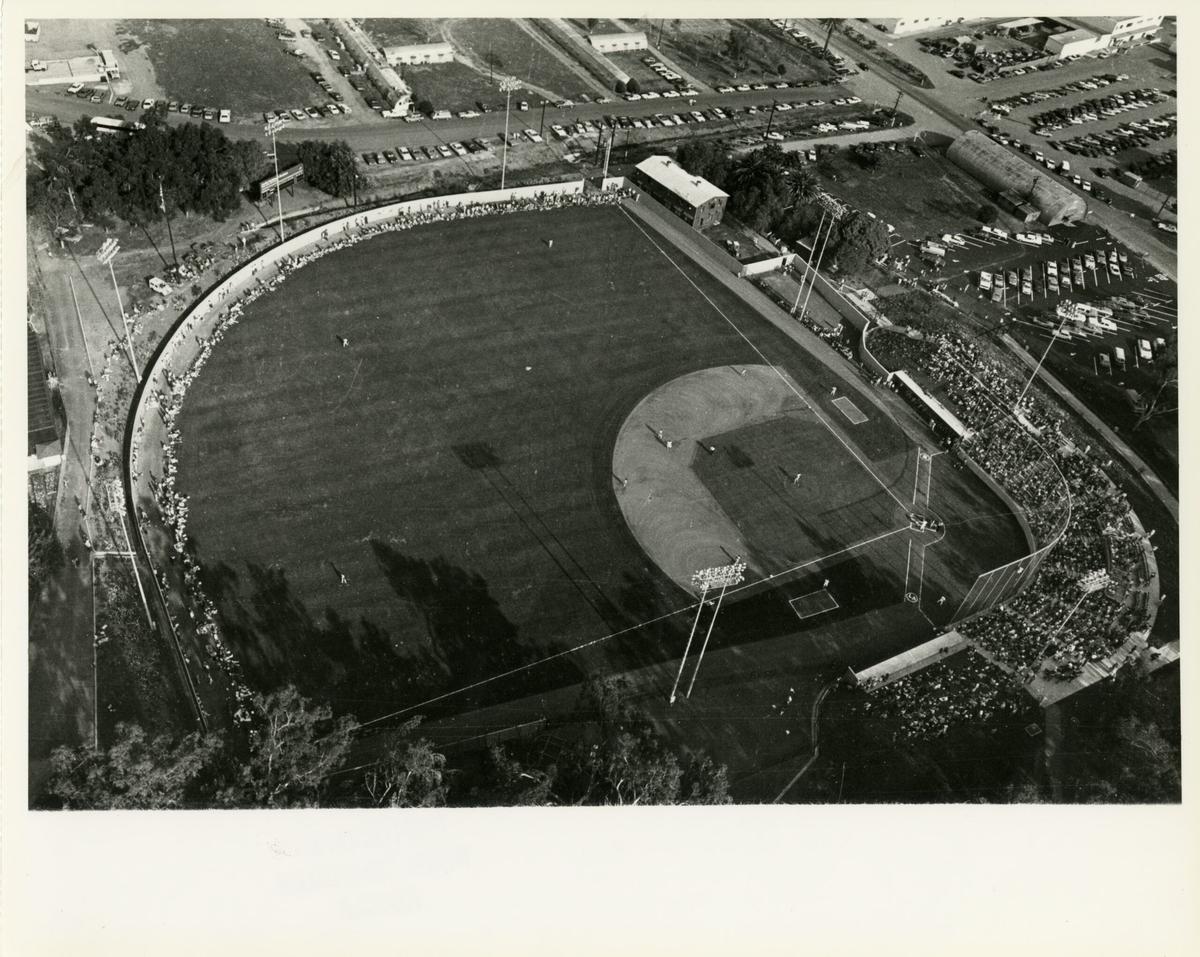

Scott sometimes subleased space to other entities, such as 20th Century Fox, which stored film equipment on the grounds. Under an arrangement with UCLA, he took in more than $4.5 million to serve as the premier parking service for events held at the university’s Jackie Robinson Stadium — which had been controversially constructed on VA land in the early 1980s.

But Scott’s scheme inhibited the West LA VA from reconstructing a well-connected living space for veterans. In an audit of campus land-use agreements, the VA’s Office of Inspector General would later note that the “large amount of paved parking areas contributes to an unpleasant walking experience, a lack of mobility, an emphasis on personal vehicles over other methods of transportation, and isolates parts of campus from one another.”

In an apparent attempt to blunt public criticism, Scott touted his entrepreneurialism as a form of charity. Because he was paying rent to the VA, he posted big signs across his lots that read: “Parking Fees Help Assist Programs that Benefit U.S. Veterans.” He and other lot operators also offered free or discounted parking to veterans — a perk that, for the city’s thousands of homeless former service members, meant little.

But because parking is a cash business, Scott seemed to figure that no one would notice if he skimmed a bit off the top, and he began enlisting employees to provide him with off-the-books cash. One parking lot manager testified that he regularly delivered payments of around $1,000 to Scott.

Scott formalized the embezzlement by creating a fraudulent set of books for the VA that obscured Westside’s real profits. He spread his off-the-books cash over five bank accounts, then used much of it to support a glitzy lifestyle befitting a Hollywood star. Scott bought three luxury condos worth a cumulative $7 million, plus a lot’s worth of collectable cars that included three Ferraris and several classic Corvettes. He also acquired a cigarette boat that he docked in Miami.

Agents seized high end vehicles during today's arrest of man suspected of defrauding #VeteransAffairs of $11 Million https://t.co/dZUp1OJn4n pic.twitter.com/LB6NwYS12f

— FBI Los Angeles (@FBILosAngeles) November 9, 2017

Around 2003, Tillman, the VA contract officer, became complicit — Scott’s man on the take. A few months prior, Scott offhandedly told Tillman he should reach out to him should he ever need “anything.” Shortly after, Tillman told Scott he had a family emergency and needed a few thousand bucks. A few days later, the two met inside Tillman’s cramped office on VA grounds, where Scott handed him a FedEx envelope containing $6,000 in $100 bills. There was no agreement, no stated quid pro quo. But the payments continued.

Each month, Scott delivered a cash-stuffed envelope to Tillman, either at his office or over a meal at a nearby restaurant in Brentwood. According to federal records, Scott sometimes suggested to Tillman that he’d formed a similar arrangement with a contract officer at UCLA.

It took 14 years before Scott’s parking scheme was uncovered. The lead investigator on the case was Michael Torbic, an FBI special agent and certified public accountant who, alongside other officials at the bureau’s public corruption squad, forensically untangled Westside’s finances. Once investigators began asking Tillman questions, he immediately put in for his VA retirement, hoping to secure his pension and, perhaps, skip town. He ultimately agreed to cooperate with the feds and wear a wire.

Scott started to feel the government’s heat and began communicating over burner phones. Before long, he suspected that Tillman might have flipped. “You told me a hundred times you weren’t going to rat out on me,” he said in one taped conversation. “If I go down, you go down.”

In 2016, as the government closed in, Scott hatched a daring exit plan: to leave his wife and flee to either Costa Rica or Panama, perhaps in his cigarette boat. Instead, he surrendered peacefully in 2017 and was convicted on an array of fraud charges. The scheme had provided Scott with a long stretch as a member of the one percent and padded Tillman’s pocket to the tune of nearly $300,000. It had also deprived the VA of $13 million.

Forces at Play

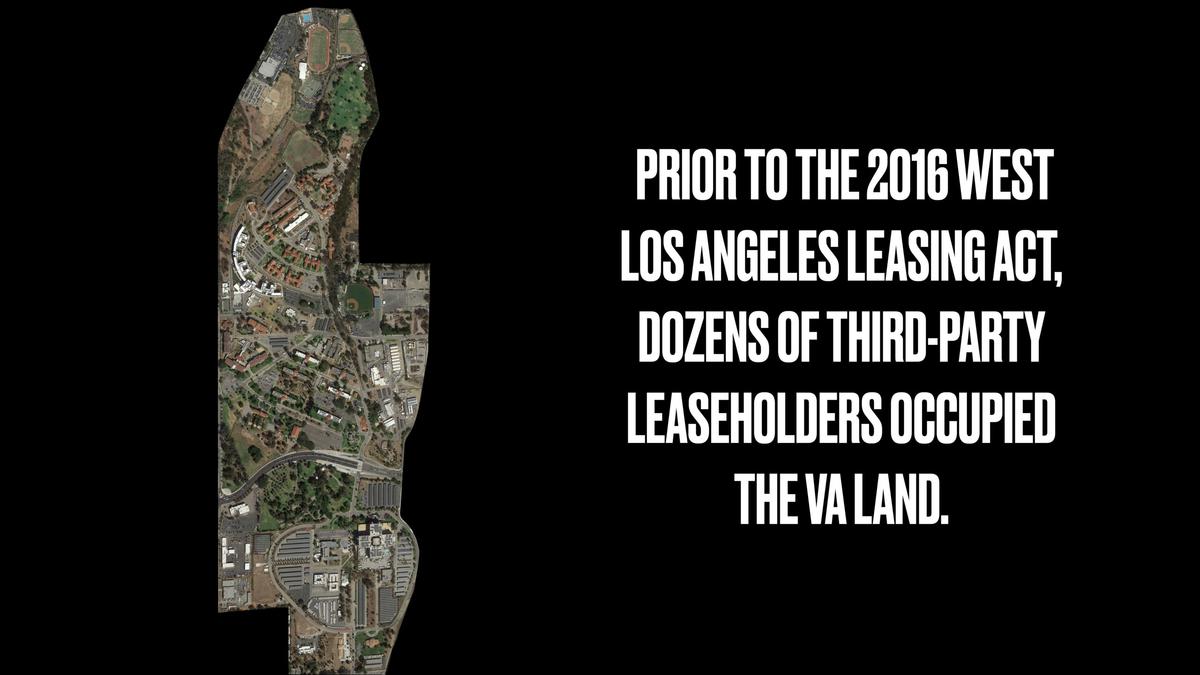

If the decades following the 1971 San Fernando earthquake were marked by fruitless government efforts to revive the crumbling West LA VA facility for veteran use, the last quarter century has been defined by unceasing energy among private forces to seize the land for their own lucrative means.

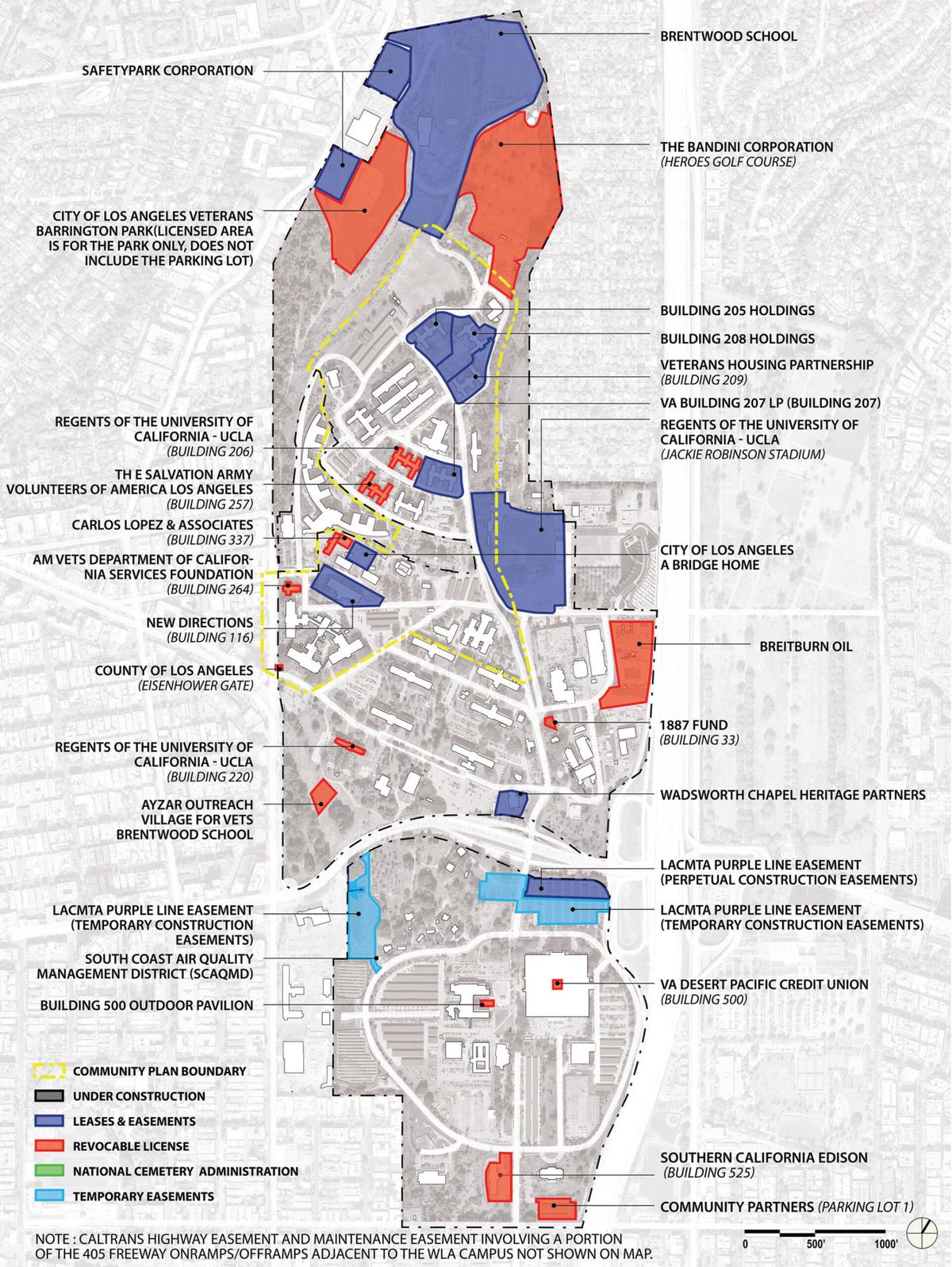

In its 2018 audit, the VA’s Office of Inspector General found that more than 60% of campus land-use agreements were illegal or improper, including for a dog park, sports fields, private offices, theatrical production space, a parrot sanctuary, and a private K-12 day school. Of the hundreds of acres originally deeded to house veterans, a tiny fraction is now in use for emergency, transitional, or permanent veteran homes — including 147 tiny shelters.

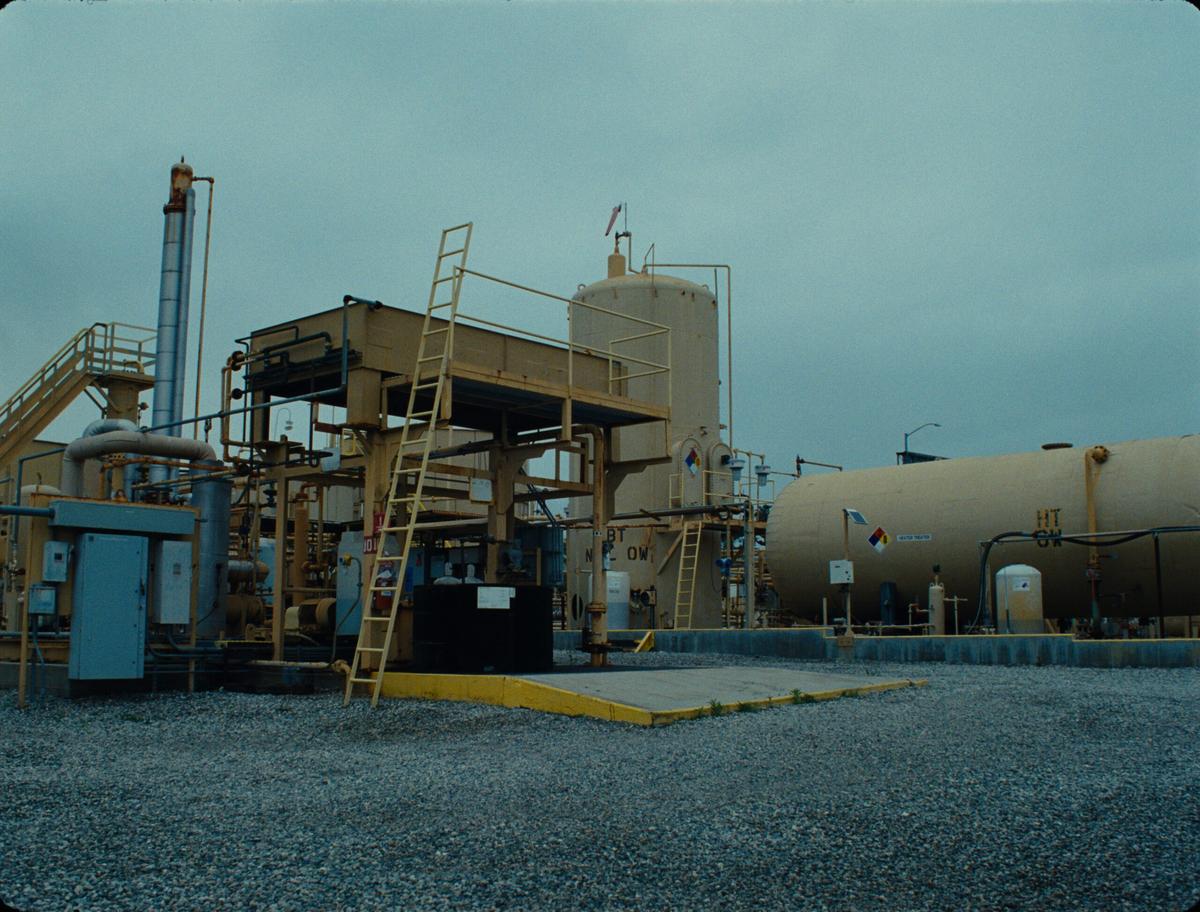

Westside Services may be gone, but other organizations continue to operate on large swaths of West LA VA land, even though their presence has been declared illegal by veterans’ advocates, lawyers, and the VA’s own investigators. This includes the Brentwood School, which was leased 22 acres, and the City of Los Angeles, which rents 12. A modest oil drilling operation located on campus, just outside the gates of the Los Angeles National Cemetery, pumps crude from beneath neighboring nonveteran land and donates just 2.5% of its gross production to the LA chapter of the Disabled American Veterans — not to the VA — for that privilege.

Many VA critics say developments that have been repeatedly deemed illegal are allowed because some of the city’s most powerful entities, including politicians and members of the Hollywood elite, have pushed for them. Other critics point to the logistical headaches associated with removing these brick-and-mortar tenants and simply shrug their shoulders.

Like Scott with his patriotic parking sign, several entities operating on campus today say their efforts chiefly benefit veterans, but when profit and promotion enter the picture, it’s difficult to know what comes first. For instance, the City of Los Angeles leased and maintained a parkland on the VA campus. The park became popular with neighborhood residents but was closed in 2016, after its lease went under examination following the January 2015 settlement of the Valentini v. Shinseki lawsuit. When it reopened soon after, the city renamed the space Veterans’ Barrington Park, from Barrington Park, and pledged to spend $200,000 to employ veterans with park-related jobs and to build a memorial in the space. The resulting monument consists of five plaques — representing each military branch, pre-Space Force — in the dirt situated near the parking lot, a display dwarfed by the adjacent sports fields and off-leash dog run.

Some veterans have equated what is happening here with a far bigger LA story, one in which lawmakers and government officials forged dubious ties with real estate developers while subverting the interests of the public. “A lot of what’s going on here ties right into the pay-for-play corruption that you see going on at LA City Hall,” Rob Reynolds, a veteran turned scrappy agitator for VA housing, told Los Angeles magazine in 2020.

The players involved in privatizing parts of the West LA VA campus have often seemed as concerned with drafting a happy narrative as they are with securing their slice. In a 2015 settlement agreement between the VA and homeless veterans, the judge, James Otero, mandated the VA to rebuild housing on the campus. But he also ordered the two parties to “coordinate a unified, positive message to stakeholders, the press, and the community” — a provision that was perhaps inevitable in a place like Tinseltown, where a good story is everything.

This kind of framing has turned the West LA campus into a public relations tool where everyone from President Joe Biden to Arnold Schwarzenegger to Rihanna appear as veterans advocates, whether their motives are truly selfless or not. All this has created incongruities between the rhetoric around LA’s veterans in need and their realities living on the streets.

Today, many veterans feel the private organizations present on VA grounds are ripping them off — a sense compounded by the fact that Tillman, who was involved in the parking lot scheme, represented the VA in a slew of contract negotiations, including with UCLA and the Brentwood School, two institutions seen to have sweetheart deals. When reached for comment, neither the VA nor UCLA answered questions about potential Tillman-negotiated contracts. A representative for Brentwood School says Tillman was gone, in no way involved when the current lease was negotiated, and that all leases have been reviewed and approved through the Department of Veteran Affairs in Washington.

Lessees that operate on campus today purport to deliver direct services and financial support to veterans, assistance that is legally mandated as part of quiet deals that have allowed them to remain on campus. But few tenants provide the one thing that veterans want most: housing.

Playing the field

Of all the private interests operating on the West LA VA campus, UCLA is arguably the most powerful. The school has close ties with city, state, and federal officials caught up in the VA grounds’ war and wields special leverage with the department through an academic affiliation dating back to the 1940s that provides the West LA hospital with clinical staff and research resources crucial to its ability to provide care for veterans. All of this has allowed the university to operate with unprecedented impunity.

The university has leased more than 10 acres on the VA campus dating back to 1981. That February, UCLA held its first game at a massive new baseball facility that the VA allowed to be built on campus grounds. “Located on the site of old Sawtelle Field, Jackie Robinson Stadium provides the Bruins with one of the top college baseball fields in the nation,” reads a 2013 description of the facility that notes its verdant setting “along trees in a natural environment.”

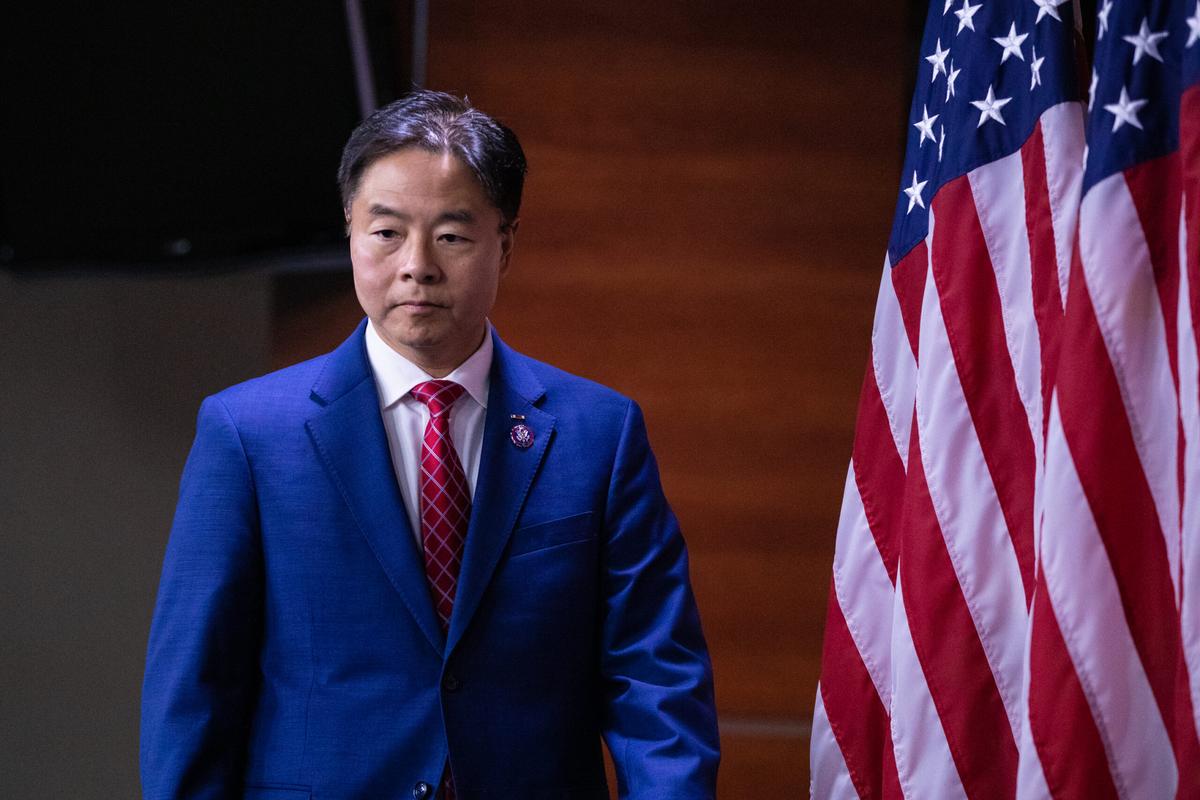

In August 2013, a federal judge deemed the arrangement, and eight others, illegal. In response, the university secured what someone involved in the execution of the VA’s leasing agreements described as a “special relationship” in the form of a lease for the stadium involving a 10-year commitment to pay rent and provide at least $13.5 million in in-kind support to the veterans. It was tucked into the West LA Leasing Act, a 2016 law co-authored by U.S. Sen. Dianne Feinstein and U.S. Rep. Ted Lieu, two California lawmakers with close ties to the school. “They did that because the regents are the most juiced-up players in California life,” explains a source involved in the leasing efforts, “and because VA needs a huge number of UCLA medical residents.”

This exemption emboldened UCLA to expand its footprint via the stadium through a practice field named after another famous Dodgers ballplayer, Ralph Branca. In a January 2021 call discussing the plan that was later leaked to the press, VA brass worried that “testy” veterans’ advocates — already vocal about the growing “Veterans Row” encampment of homeless vets on the sidewalk outside VA gates during the COVID-19 pandemic — would “get up in arms” over the deal, which would allow the construction in exchange for the VA regaining use of some parking spaces. The practice field opened the following year.

The ballpark expansion wasn’t UCLA’s first attempt at growing its recreational footprint on the VA’s land. Ten years before, UCLA nearly gained access to a nine-hole golf course on campus originally given by the Hillcrest Country Club in 1946 as a gift to World War II veterans. In 2009, the course was padlocked for what the VA initially said were “operation issues.” In fact, it was shuttered after investigators found employees had embezzled $200,000 in green fees and concessions revenue.

According to 2011 reporting by the Los Angeles Times, UCLA explored a partnership with U.S.Vets, a nonprofit housing developer run by the son of Gregory Peck, Steve, for management of the course. According to Peck, UCLA and U.S.Vets discussed an arrangement where the university’s golf team could use the course during certain hours “in return for some support and the veterans who would be using it.” Amid vocal concerns from veterans that the school would prioritize students over veterans and the public, the partnership died. The course management contract went to the Bandini Foundation, a group led by an heir to the 19th-century landholders who donated the land the VA now occupies. “From our point of view, it was never contemplated that [UCLA] would manage the course,” Peck says.

In a statement, UCLA notes that the university pays for its use of the VA property, including the baseball complex, consistent with the terms of the Leasing Act and its lease. “The latest VA Congressionally Mandated Report, issued in 2023, shows that UCLA provided annual compensation — in rent, direct payments, and in-kind compensation — totaling $2,383,477,” the statement says. “This exceeds the amount required under the Leasing Act.”

Indeed, UCLA pays around $300,000 a year in rent, but after the 2013 ruling, to keep the land they had been leased, UCLA and other leasing entities became legally bound to provide a robust slate of veteran-centric services and support.

One such program the university launched was a Veterans Legal Clinic that seemed attractive on paper but proved less helpful in practice. Two former students, who requested anonymity over fear of losing future work as legal professionals, contend that the clinic prioritized academic busy work over tangible assistance. “I’d say we spent less than half our time helping veterans,” one says. “We were like 1.5 miles from a crisis we could be alleviating, but it didn’t feel like that was the focus.”

The clinic launched with $400,000 and two professors, a relatively modest initiative when compared to some of the school’s other clinics, the students say. “Given the value UCLA receives from the VA land alone, it’s clear that we are getting more from them than the VA is getting from us,” the second former student says.

In response to inquiries, UCLA said the UCLA Veterans Legal Clinic has assisted approximately 900 veterans and secured over $6 million in estimated lifetime benefits on their behalf. Within the last few years, the clinic added three staff members, two staff attorneys, and one client services clerk, doubling the staffing level of the original annual lease commitment.

UCLA established other veteran-centric programs — including the UCLA/VA Family Resource and Wellbeing Center, and the UCLA/VA Center of Excellence on Veteran Resilience and Recovery — when it launched the Veterans Legal Clinic as part of the in-kind services required to secure the stadium rights.

The person involved in the execution of the West LA VA’s development said many offerings from leasing interests seemed broadly insufficient in meeting vets’ needs but still met minimum requirements to stay in the government’s good graces. “Congress gave them a really generous, I think, pretty easy-to-meet test,” he says. “And I think they meet it.”

But the VA was on the hook, too. A review of publicly available compensation data for the UCLA faculty working on these VA programs reveals the VA paid many of them six-figure salaries in 2022 — on top of their six-figure UCLA earnings — for serving and supporting, as the law allows, the “medical, clinical, therapeutic, dietary, rehabilitative, legal, mental, spiritual, physical, recreational, research, and counseling needs of veterans and their families.”

The analysis shows VA paid more than $2 million in salaries to UCLA staff working on research and services for veterans in 2022 — payments made at the same time that Knock LA reports the VA’s Care, Treatment, and Rehabilitative Services (CTRS) program denied petitions from unhoused veterans because it lacked vacancy in its limited supply of tiny homes. According to a VA spokesperson, the tiny shelter occupancy rate hovered between 85% to 95% in 2022, and over the course of the year, the department added 30 units. CTRS also offered six “drop-in” tiny shelters, available at any time for overnight housing.

Neither the VA nor UCLA responded to specific questions or follow-ups about these salaries.

Additionally, UCLA’s influence on the VA campus would sometimes surface in curious ways. For decades, the university gave American Legion clubs priority to use Jackie Robinson Stadium when its students didn’t need it; the Legion clubs had, after all, played on the grounds since before the university moved its baseball team there in 1933. But around 2010, that agreement was canceled without notice.

“I called UCLA almost on a daily basis to see what we can do to get our field back,” Legion member and Purple Heart recipient Julio Yniguez told Knock LA in 2021. “They eventually let us back, but UCLA wanted us to pay $500 to use lights for our games, and we couldn’t afford that.”

Compounded Interests

Founded in 1972, the Brentwood School has reared the offspring of the city’s most powerful people, including Schwarzenegger, and counts Maroon 5 frontman Adam Levine as an alum. Its predecessor, the Brentwood Military Academy, had existed since 1902 in several locations as the Urban Military Academy before settling in Brentwood and changing its name. Today, the private, co-ed, K-12 day school is one of Los Angeles’ most expensive and esteemed private schools — not just a vessel for the influential, but an influence in its own right — and has little to do with preparing students for military service.

Since 2014, the elite academy has dropped nearly $1 million on a white-shoe Washington lobbying firm. Last year, a bill floated by an Oregon U.S. House member included an amendment for Brentwood that mirrored UCLA’s deal to secure land on the West LA VA campus. Kathryn Monet, the chief executive officer of the National Coalition for Homeless Veterans, recalled hearing from congressional staffers about Brentwood School lobbyists working Capitol Hill to retain their facilities. “We all know that in LA, land is everything,” she said, “and in that city, there’s not much of it left.”

To the frustration of veterans’ advocates, the VA testified in support of the Brentwood amendment, though it got cut from the bill before the House passed it in December. Brentwood School nonetheless remains on West LA VA land, promoting its veteran services while benefiting from the VA’s unwillingness to aggressively confront powerful lessees.

In 2001, the Brentwood School built what is now called the Veterans Center for Recreation and Education (VCRE) on VA grounds. There, the school provides veterans “services in physical recreation, health and wellness, education, as well as a range of special programs and events, all on facilities built and maintained by Brentwood School,” according to its website, published as early as September 2019 — which did not mention that the land is leased from the VA. An updated website appearing more than four years later, after veterans brought new legal challenges to its lease, states, “the rent Brentwood School pays for its 22-acre lease is required by law to stay local and be used for priorities at the West LA campus, including housing and emergency shelter, construction, maintenance, and renovation.” That annual rent comes to $850,000 per year, with required in-kind services of $918,000, which the school has regularly exceeded by holding events for veterans and their families, including movie screenings, picnics, food and clothing drives, educational services, transportation, and scholarships.

“The lease directly benefits Veterans in West Los Angeles — the funding it provides stays local,” Brentwood School said in a statement. “The school’s valued partnership with the VA, dating back to 1972, has always been a mutually beneficial collaboration.” The school notes veterans services that include camp and school scholarships for veterans’ children, fitness and educational programming, the funding for 20 CTRS shelters, and move-in kits with essential supplies for new residents in campus housing.

Functionally, the VCRE facilities are used by students and staff, with veterans allowed in only for limited windows — even though the school’s use of the land is explicitly required to be “veteran-centric.” Veterans are given access to the swimming pool, for instance, every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday between 5:30 and 7:30 a.m. In 2023 there were 5,883 visits by a total of 1,329 veterans, the school reports.

One of those veterans is Joel Ayers, an Air Force veteran who served three deployments in Afghanistan and struggled with heroin and alcohol addiction after he came home. He ultimately landed on the streets during the pandemic, losing his job due to his issues with substance abuse. He started using the Brentwood School’s workout facilities and received acupuncture therapy from UCLA staff after securing a spot in the VA’s domiciliary program in 2021. Besides his housing, Ayers says the gym community he’s found via the school is “the next most crucial part of my sobriety,” adding that he sees the leasing interests as positive forces. “They’re weaved into the community of the campus,” he says.

Veteran centricity is not in question when it comes to Marcie Polier Swartz, though depending on whom you talk to, the Brentwood businesswoman is either a veterans’ advocate or their opponent. Polier Swartz is the cofounder of Village for Vets, a nonprofit that provides veterans with basic supplies such as food, clothing, and sleeping bags. Since 2021, the group has provided dozens of tiny homes to homeless veterans living on the West LA VA campus, including 25 donated by Schwarzenegger through the organization. “Following Schwarzenegger’s donation, Village for Vets has received over $100k in new donations from $120+ new donors, as well as gaining thousands of new followers and millions of views,” the nonprofit states on its website.

But Polier Swartz has her own stake in the fight: hundreds of campus parking spaces she secured for use by customers of the Brentwood businesses located along Barrington Avenue, opposite the West LA VA campus. In late 2015, when the federal register was open to public comments concerning a new campus master plan, Polier Swartz wrote that Brentwood’s business district “will die if we are not allowed to use the parking lot.”

Polier Swartz founded and led a box office research company that she sold for millions to data giant Nielsen in the 1990s. She has been one of the most vocal advocates for Brentwood residents and business owners. Swartz and other local leaders have worked aggressively to maintain access to “our dog park and our parking lot,” as she wrote in a 2015 op-ed in Brentwood News that opposed a new VA land-use plan, adding, “We hope not to see our neighborhood destroyed.” Swartz could not be reached for comment.

Lawmakers and VA leaders have repeatedly and publicly promised the campus land would never be prioritized for private interests. In 2000, Philip Thomas, then the chief executive officer of the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, told the Los Angeles Times the campus would remain in veteran hands. “We are not going to be divvying up the land,” he said. “It will remain intact.” Two years later — and two days after a state-run nursing home for veterans was announced to be built on the West LA campus — the VA suspended Thomas over suspicions that he’d filed an erroneous worker’s disability claim, according to a Los Angeles Times report. His promise regarding the land also didn’t hold up.

Former U.S. Rep. Henry Waxman, who long represented the campus in Congress, tried to understand exactly how much money had come in and where it was being used. “There was a lot of secretiveness with people who were running the VA facility because of these leases that they had,” Waxman said in a May 2024 interview. “But as we looked at them, we were concerned about whether this was a fair economic exchange.”

In 2012, the Democrat told NPR that “the West LA VA was in business for itself.” During the George W. Bush administration, he said then-VA Secretary Jim Nicholson told him he supported plans to use the land for condos, office towers, even a shopping mall.

“He told me, when I went to meet with him, that he was a real estate developer, and this was prime real estate, and we could make a lot of money by commercializing it, selling it off, and letting people build whatever they wanted to build,” Waxman told the media outlet. “And then he said that money could be used for veterans.” Two decades on, the VA has cycled through a half dozen VA secretaries, most of whom have supported some version of this plan, extending old leases while cementing new ones.

Shortly after Thomas left in 2003, the VA forged a new agreement with the Westside Breakers, a youth soccer club. Starting in 2011 and lasting for about a decade, the Breakers enjoyed access to MacArthur Field on campus without a written lease agreement.

When the VA’s Inspector General raised concerns about the arrangement in 2018, a local hospital director said she’d allowed the club access to the land pending construction of veteran housing. The Breakers paid the VA between $40,000 and $55,000 annually for their access until 2017, when payment inexplicably stopped while the team remained.

Straw men, strong responses

Over the years, the VA has launched limited accountability efforts involving the land, to mixed results. In 2015, the agency sent the Breakers a notice to vacate the premises, but they remained until 2020 or so. At the dog park, civilians were intended to only access this partially shaded, fenced-in area if given prior written approval by the VA. And yet, in 2018, federal watchdogs could not find “any evidence of requests or approvals for community use of the park.”

Shortly after, the VA locked up the park. It reopened a day later, thanks to what the Los Angeles Times described as a “well-connected” dog owner. Even Eric Garcetti, then the mayor of Los Angeles, offered support for both the dog park and Jackie Robinson stadium — positions seemingly at odds with his failed political pledge to end veteran homelessness by 2015.

It’s not clear why the VA hasn’t responded more aggressively to the institutional squatters on their land. When approached for comment, VA declined to answer specific questions on leases and land use agreements citing pending litigation. However, one senior VA official, in explaining the Brentwood School’s continued presence on campus, told CNN in April 2022 that “if we terminated the lease, they would take us to court.” In other words, the VA signed leases that triggered a lawsuit from the veterans, but getting out of those leases will trigger a lawsuit from the lessees.

The VA has terminated a series of agreements with smaller footprints — though many of them had genuinely veteran-centric service missions, including chapters of the Disabled American Veterans and the Jewish War Veterans, as well as a peer-support group called Vet-to-Vet and the Twilight Brigade, a nonprofit that provides comfort and caregiving to dying VA patients. “The message was ‘get out,’” the brigade’s cofounder, Dannion Brinkley, recalls. “I said, ‘What’s the reason?’ and got nothing.”

Dr. Lorin Lindner described a similar series of events. A clinical psychologist who served at the West LA VA for decades, Lindner spent her free time rescuing damaged birds. She eventually merged her interests in the form of a parrot sanctuary on the VA grounds. The department leased to her part of a cracked basketball court near the old Veterans Garden for a work-therapy program in which VA patients spent time with her birds and cared for them in exchange for a stipend.

The sanctuary yielded therapeutic benefits for the vets and glowing press coverage, including a feature in The New York Times Magazine. “The guys would talk to the birds, but they wouldn’t talk to me — as the shrink,” Lindner says. Time and again, she watched the birds melt hardened veterans into sweet, emotional creatures.

The sanctuary took up an eighth of an acre. When veterans first sued the VA in 2011 to rebuild housing, she said the group’s lawyers at the ACLU assured her they supported its presence. Yet in 2018, she was forced to relocate her sanctuary off campus while far larger forces were allowed to stay. “Look at the buildings, follow the money,” she says. “The powerful people got what they could and the rest of us were kicked aside.”

The 2018 VA Office of Inspector General report noted that its auditors visited the sanctuary on three occasions only to find it padlocked, and said that Lindner’s association failed to submit any quarterly reports detailing veteran outcomes, as its lease required.

The Salvation Army had two buildings and provided transitional housing and services to veterans through its Haven Program. Their partial eviction resulted in a net loss of 130 beds for women, older veterans, and those in an alcohol and drug treatment program. In an interview with the Los Angeles Times, the then-director of the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System said the closures were due to poor performance. “Our veterans are not happy,” Pilar Buelna, the Salvation Army’s local director of social services, countered. “They should have been more strategic with the transition.”

The homeless industrial complex

If one building is emblematic of the West LA VA’s 136-year potential to serve — and frustrate — veterans, it’s Building 209. The campus’s first residential building to be opened after the Valentini v. Shinseki settlement, it shows how the property’s map isn’t the only thing that’s been carved up: The housing itself is being whittled away by third-party leases, too. Building 209 opened in June 2015, after a $20 million, VA-funded renovation that had been approved in 2010. In a statement for the ribbon-cutting ceremony, Rep. Lieu — whose former employer, Munger, Tolles & Olson, had negotiated the settlement on behalf of the unhoused veterans — noted, “Building 209 will be opened to offer veterans long-term supportive housing.”

The 55-unit building accommodated veterans participating in a transitional Compensated Work Therapy program, an initiative that has been popular among veterans and that the VA continues to promote today. In a 2015 interview with the Los Angeles Times, Army veteran Keith Hudson, then 52, described his home in Building 209 as “state of the art,” “brand new,” and “like an apartment complex and a five-star hotel combined into one.” Hudson was employed as a VA hospital housekeeper, the paper reported.

According to Vince Kane, then a special adviser on homelessness to VA Secretary Bob McDonald, as the apartment building came online, other homelessness solutions were being explored. “The thinking was that it needed to be more consistent with the vision and the mission of the campus, which was to create permanent housing and to target the aging, chronically homeless, those suffering from serious mental illness,” Kane says.

Meanwhile, the West LA Leasing Act was working its way through the legislature. The legislation, which was signed into law by President Obama in 2016, allowed the VA to contract with third-party organizations to manage its properties on leases that could last up to 99 years. This meant the department would have the legal authority to outsource both building and case management services for veterans to outside groups. As a result of the legislation, the VA contracted with construction company Shangri-La and supportive housing provider Step Up on Second Street — known together as the Veterans Housing Partnership — in May 2017 to run and maintain Building 209.

“So that building transitioned from its original intent” as a Compensation Work Therapy unit, Kane says. It went from being temporary housing that helped vets stabilize their lives as they began to work jobs that paid enough for them to afford housing to permanent supportive housing for aging, homeless, and disabled vets. “That was considered a more effective and more needed solution to end veteran homelessness,” he says. This change prompted a second opening ceremony for the building in June 2017, a bizarre moment in which the VA patted itself on the back for a milestone that had occurred two years prior.

“This ribbon cutting represents a step forward in restoring the West LA VA property to the Old Soldiers Home it was always intended to be,” read Rep. Lieu’s statement for the occasion. “These units are being created on the West Los Angeles VA Campus as a result of legislation I authored with Senator Feinstein last year.” He was referring to the 2016 West LA Leasing Act.

The trouble was, the units had already been “created” — and occupied by CWT veterans — and when the building changed management, residents were then required to be eligible for housing under HUD-VASH (Housing and Urban Development – Veteran Affairs Supportive Housing) vouchers.

Veterans and veteran advocates say that all but six residents of Building 209 were removed from the building, which was then mostly reoccupied by new veterans. When reached for comment, a representative for the VA did not respond to questions about the changes in Building 209, “due to ongoing litigation.”

Kane says no veterans were displaced when Building 209 changed from CWT to permanent supportive housing. He says some vets could have graduated from the program or moved to other programs. Other service members may have qualified for a Housing and Urban Development (HUD) voucher and transitioned into permanent supportive housing. “Nobody was moved to the streets,” Kane says. “Everybody got some type of housing or continued in some type of treatment program…. I made sure that nobody fell through the cracks.”

A key difference in how the building was run in 2015 versus its reintroduction in 2017 was its funding. According to Kane, prior to the Leasing Act, the CWT housing was funded by the VA. But the HUD-VASH system doesn’t draw housing costs from the VA budget. Instead, veterans are issued vouchers funded by HUD that pay the rent.

The VA also now works with third parties like Step Up and provides wraparound case management that vets need to manage ongoing hurdles to their health and well-being — and not just in Building 209, but in all the enhanced-use lease apartment buildings on the campus, which now includes Buildings 205, 207, and 208. In theory, these offerings should provide a robust safety net for disabled service members. In reality, many vets find the support lacking.

“There is a disconnect between the VA’s responsibilities for veterans and what is in the best interest of the people they farm these things out to,” says Jeffrey Powers, the named plaintiff in the class action lawsuit veterans have filed against the VA.

Powers lives in Building 205, which Shangri-La renovated alongside 208 starting in 2019. He and other vets find the arrangement underwhelming. According to the 62-year-old Navy veteran, his apartment has no oven, no closets, “shoddy” electrical wiring, and the kitchen-area sink isn’t big enough to hold a regular dinner-sized plate. “They had an opportunity to do something veterans were clamoring to get into,” he says. “But this is my last choice.”

“They’re given a lump sum to renovate the buildings, so it’s in their best interest to spend as little as possible to do that so that they can keep more,” Powers says. Shangri-La did not respond to requests for comment on this story.

According to VA records, Step Up and Shangri-La paid around $1,900 per month to lease Building 209 between 2017 and 2021. Recently, a one-person apartment in one of the buildings was leased with a base rent of $2,960. That’s a market rate, and with 53 housing units in the smallest apartment building currently offering permanent housing on the West LA VA campus, it provides the contractors an approximate $1.9 million in annual rental income for that one structure.

“These buildings operate in many ways just like typical apartment buildings,” says Step Up president and CEO Tod Lipka, referring to the operational costs including maintenance, property management, insurance, capital reserves, and utilities, which veterans do not pay. “That is an expense we bear,” he says.

“With all these combined costs, our responsibility to pay the ongoing expenses of the buildings essentially means that they break even,” Lipka says. “There is no $1.9 million surplus.”

The buildings also provide supportive, wraparound case-management services, including independent living skills training — such as cooking, shopping, and cleaning classes — and transportation to and from VA appointments, as well as other activities. Lipka notes these are largely funded through a contract with the VA. Step Up has 13 full-time supportive staff on site for its 180 tenants.

Connections or Conflicts?

While the VA had renovated Building 209 itself, there were many more in need of revival. In November 2018, the VA picked a trio of developers to reconstruct the campus to its former splendor: Thomas Safran and Associates (TSA), Century Housing, and U.S.VETS. Together, the companies formed an organization called the West Los Angeles Veterans Collective (WLAVC), and in June 2022 — after 43 months of public hearings, federal red tape, and a global pandemic that brutalized the unhoused — its contract with the VA was finally executed. TSA could not be reached for comment. Representatives for WLAVC did not respond to requests for comment by the publication deadline.

The companies’ agreements are 99-year enhanced-use leases that have renewed veterans’ concerns over the land’s privatization. The VA contended this term was essential — the federal agency had to deputize private interests to control and build on the land because it lacked the statutory authority after the 1958 law that revamped the VA’s structure and did away with its old Soldiers Home system. “It’s not that VA doesn’t want to create housing, we don’t have the authority to do it,” says John Kuhn, Deputy Medical Center Director at the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System. “If Congress wants to give us the authority, VA would build housing.”

But veterans’ advocates note the VA’s historic role in housing veterans and point to previous VA claims of housing powers, including in 2007 for a project to transform three vacant Los Angeles buildings into livable units. The VA notes it has invested roughly $175 million over the past four years in infrastructure improvements on the property to support housing.

On the West LA VA campus, there is also Building 209’s renovation, funded and briefly run by the VA, as well as the tiny shelters in CTRS, which Kuhn points out represent “an interesting conundrum.” The government didn’t build the units; the tiny shelters were all donated and turned over to the VA, he says.

“Now that we have the authority to run them and repair them, do we also have the authority to purchase them?” he asks. Kuhn says that — and whether VA can build new tiny sheds — are outstanding questions.

No deadlines or penalties were tied to the development deals, which have been plagued by shifting targets and significant delays. In the 2016 draft master plan, the VA committed to the creation of 1,200 permanent supportive housing units in a decade’s time. The department initially estimated having 770 of those units ready by 2022, but the developers have, as of April 2024, completed just 233 units. In response to inquiries, VA says it anticipates having nearly 500 units open by January 2025 and 730 units open by the close of that year.

The developers have to fundraise much of the project’s $1.1 billion budget, which slows down the process. In May 2022, WLAVC launched a campaign to raise $188 million in private money to build the veteran housing — according to the Veterans Collective, nearly all of the project’s cost will come from government sources. The gap funding effort enlisted a star-studded cast of canvassers, including NBCUniversal, the CEO of United Talent Agency, then-mayor Garcetti, Navy vet and HBO executive Amy Gravitt, and fellow sailor and NBA Hall of Famer David “The Admiral” Robinson.

While Thomas Safran’s mission — to build affordable housing — seemingly aligns with that of the city’s veterans, fairly or not, his ties to the VA campus’s neighboring powers has generated mistrust among the vets and their advocates. A mostly southern California-focused developer, Safran received his MBA from UCLA, where he has also been a member of the Chancellor’s Society donor group and holds an advisory board role at the university’s Ziman Center for Real Estate. The businessman, now in his late 70s, started his career at the ground floor of affordable housing, having interned at HUD in 1969, according to a 2010 profile in the Los Angeles Business Journal. Five years later, he left HUD at age 29 to “to build high-quality (affordable housing) projects indistinguishable from market-rate housing,” the Business Journal wrote.

Thomas Safran & Associates’ headquarters — a colorful transparent glass building opened in 2020 and designed by Frank Gehry — is located in Brentwood, two blocks from the VA’s San Vincente entrance and Veterans Row. In addition to his UCLA connections, TSA’s website lists Safran as a business representative on the Brentwood Neighborhood Community Council and a donor to the Brentwood School.

Since 2015, he has given nearly $10,000 to the campaign of Rep. Lieu, whose 2016 Leasing Act set up the controversial enhanced-lease structure that has given Safran’s outfit nearly 100 years of control on the VA property. That same year, Lieu attended a celebration for “my friend” Safran in Brentwood that was attended by Garcetti and other political bigwigs.

Considering Safran’s connections, raising more development money may not be as insurmountable a hurdle as it seems. According to reporting by Curbed, TSA and its partners found money for the VA project through the Los Angeles City Council in 2019. Three years later, Urbanize reported the Los Angeles County Supervisors, whose members Safran has consistently donated to, awarded the company $33.7 million to develop Building 402.

The Housing Authority of the City of Los Angeles has supported various TSA projects by acting as a bridge between the government housing programs and the housing developers. Its president and CEO, Douglas Guthrie, says Safran enjoys a positive reputation thanks, in part, to his “very demanding personal taste” that results in impressive projects.

Guthrie says Safran’s VA work is complicated by the incredibly complex and competitive financing arena, estimating that “if the VA could provide direct resources and bypass that multilayered process, then it could make a big difference.”

Guthrie adds that the VA itself has, for years, consistently failed to provide his agency with enough referrals to meet their large pool of VASH and other housing vouchers for veterans, some of which apply to completed units on the West LA VA grounds. “Right now, we could use 100 referrals a week,” Guthrie says. “And we’re getting about five or six.”

TSA has tried to expand work on the campus via hundreds of additional units not spelled out in the master plan, even as it was behind on Safran’s initially promised allotment — work that elicited scrutiny from the federal advisory committee overseeing the redevelopment. “He regards the campus as a housing factory,” a source involved with the execution of the master plan said. “He makes money each housing unit he creates.”

In June 2023, the longtime Brentwood resident became ensnared in a conflict-of-interest scandal when his company and two other firms allegedly gifted the wife of Los Angeles City Councilman Curren Price more than $150,000 between 2019 and 2021, while Price supported $4.7 million in city funding for a non-VA Safran development.

Safran isn’t the only West LA VA lessee facing legal scrutiny. In January, California’s Attorney General filed suit against Shangri-La and Step Up for misusing $114 million in state housing grants issued as part of the pandemic-era Project Homekey, a hotel-to-housing conversion program that was part of the strategy to house homeless people during the pandemic. After the suit was filed, Shangri-La and its affiliate businesses sued Shangri-La’s former CFO, alleging he diverted millions in public funds through a complex web of financial entities to support his own lavish Hollywood lifestyle. The plaintiffs are now seeking $40 million in damages.

Step Up’s Lipka said the nonprofit organization was “devastated by the failures of Shangri-La on the Homekey projects” and noted it was in the process of removing Shangri-La from all of its projects.

While the scandal doesn’t appear to involve the Shangri-La and Step Up managed properties at the VA, it has veterans on alert, partly because — with allegations of improper spending on expensive cars and luxury apartments — of its striking similarities to the parking lot embezzlement scheme from two decades earlier. This is Los Angeles, after all, a movie city that’s no stranger to ill-conceived remakes.

GET UPDATES FROM THE FRONT

Follow the veterans’ fight for housing at the West LA VA and receive court briefings from the trial.